This story is part of “Every 30 Seconds,” a collaborative public media reporting project tracing the young Latino electorate leading up to the 2020 presidential election and beyond.

With recent polls showing Joe Biden’s Latino support in Florida lagging, the former vice president is kicking off Hispanic Heritage Month on Tuesday by visiting the middle of the state, which is home to hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans. He might have started in Arizona or Texas or Pennsylvania, where another 500,000 Latino voters live. Instead, he’s starting in this winnable battleground because he can’t let it slip away.

Florida is expected to be one of a handful of critical swing states. The slightest shift in one direction or another could determine whether President Donald Trump or Biden wins the state’s 29 electoral votes — as well as the White House. The Latino vote in South Florida, where many Cuban Americans and Venezuelan Americans live, will be heavily contested, so Biden would need to rack up a big victory in central Florida to secure a win in the state.

Conversely, Trump needs to limit Biden’s margin of victory in central Florida. That’s why his campaign has invested time and energy and money there for years.

To be clear, central Florida is firmly Democratic. Biden will win there in November. But Republicans aren’t trying to win that region. They’re just trying to keep Biden’s wins in central Florida counties — particularly Orange and Osceola — as slim as possible, which could help keep Florida red.

Orange and Osceola are home to Florida’s largest Puerto Rican communities. More than 130,000 Puerto Ricans fled the island in the wake of Hurricane Maria in 2017, and tens of thousands of them have settled there in central Florida. Puerto Ricans as a whole are considered the most liberal of the major Hispanic groups in the US. But in these two counties, Republicans feel that they have an opportunity to make inroads with Puerto Rican voters because of their somewhat unique class positions and religious practices.

Some quick math shows why Orange and Osceola are crucial. In 2016, then-candidate Trump beat Hillary Clinton in Florida by a little more than 110,000 votes. In 2018, the Puerto Rican population of Orange County was more than 200,000, and almost 125,000 in Osceola. Combined, that’s approximately three times as great as Trump’s margin of victory in Florida in the last presidential election.

To win their votes, the Trump campaign has followed the advice of Puerto Rican Republicans in Florida and Puerto Rico: the president must appeal to central Florida’s Puerto Rican middle class and a growing population of Puerto Rican evangelicals. They would also like to hear messages of support for post-hurricane Puerto Rico and statehood for the island, but it seems these objectives will remain a dream so long as Trump is president.

Related: The DNC touted a diverse lineup. But some Latino leaders feel left out.

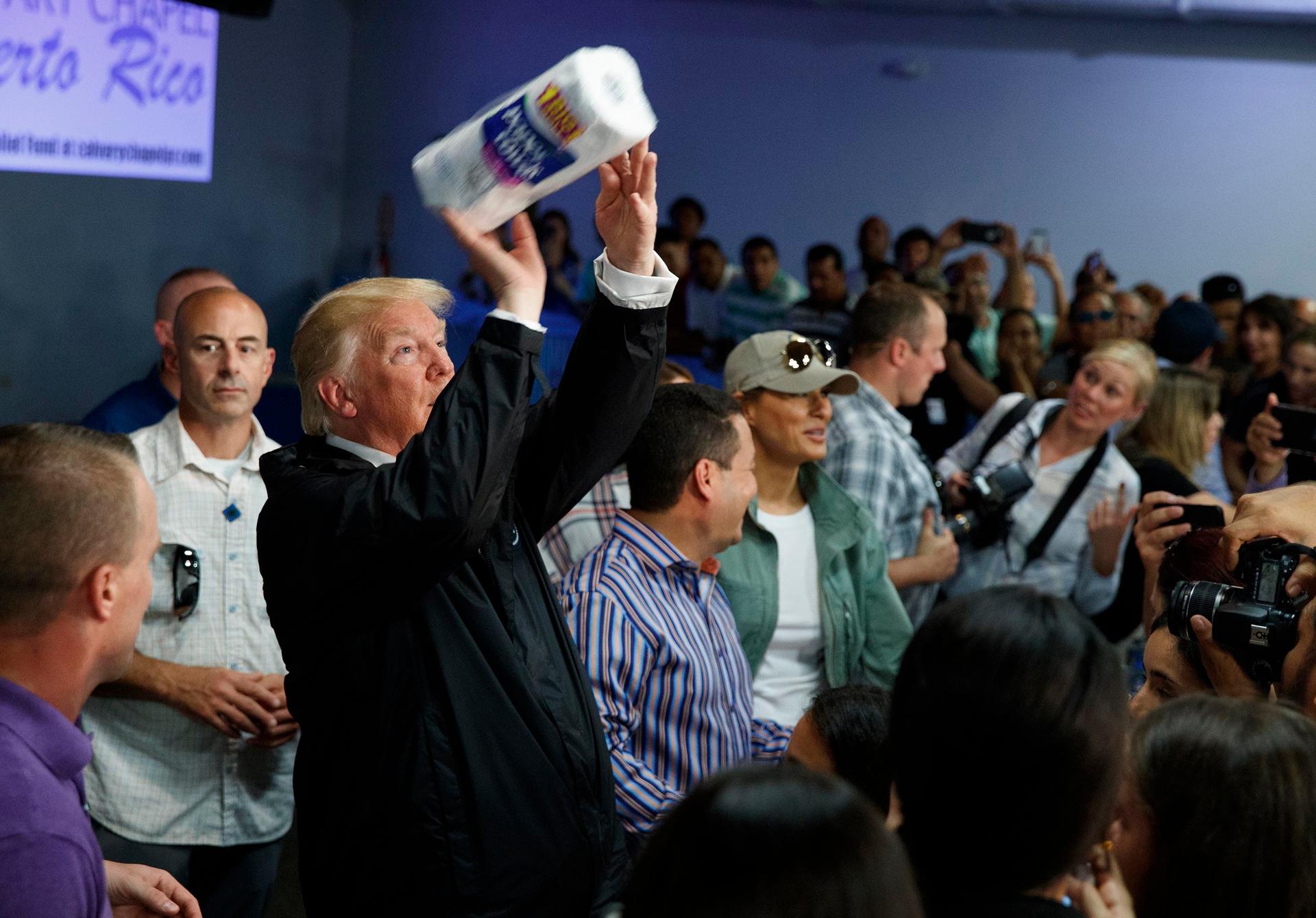

It’s hard to forget the image of Trump tossing paper towel rolls into an audience near San Juan, as though they might soak up the hurricane’s floodwaters. But Puerto Rican Republicans don’t think that will doom him. Instead, they believe Florida Gov. Rick Scott’s positive example of Republican leadership will help lift Trump. In the wake of the hurricane, Scott visited Puerto Rico several times to survey the destruction and offer Florida’s assistance in the recovery effort. As a result, he won 46% of the Hispanic vote in 2018, including more support from Puerto Ricans in central Florida than other Republican candidates received. Describing how he “showed up” after the hurricane, Scott says Trump is now “doing the same thing” by reaching out to Latino voters.

How Trump’s strategy could work

Some findings by the anthropologist Jorge Duany point to the possibility that the Trump campaign’s strategy with Puerto Ricans in central Florida could work. Duany has argued that middle-class Puerto Ricans have retired in central Florida based on lifestyle preferences instead of economic necessity. Moreover, the 2010 census revealed that compared with Puerto Ricans in New York — where the largest number of mainland Puerto Ricans live — a greater percentage of Puerto Ricans in central Florida held bachelor’s degrees, had higher median household incomes, and lived in owner-occupied housings. They also had lower rates of poverty, unemployment and jobs in the service sector.

These are all indicators of a strong middle-class identity among central Florida’s Puerto Ricans, Duany argues, which Republicans from Richard Nixon onward have seen as their greatest target of opportunity for attracting Hispanic votes. But in addition to middle-class Puerto Ricans, the Trump campaign is also appealing to the growing number of evangelical Puerto Ricans.

In the 1990s, Ralph Reed, a Republican strategist and former head of the Christian Coalition, played an important role in making sure that Republican candidates focused on statehood and evangelical Christianity. With the former off the table, they’re focusing on the latter. Reed observed that the members of the growing Puerto Rican population were also starting churches as they settled. He helped build up Puerto Rican congregations by recruiting pastors from the island who were already US citizens to set up ministries in places like Orange and Kissimmee.

Puerto Ricans have embraced evangelicalism since the early 20th century. But they’ve gained political influence in more recent years. Pastors like Gabriel Salguero and Jeanette Salguero have organized ministries at megachurches in Orlando, where they’ve encouraged civic engagement including participation in US elections. Republican outreach coordinators like Gary Berrios have worked with Latino evangelicals in Florida, and Vice President Mike Pence, accompanied by Puerto Rican leaders, has led campaign-style events at churches in Orlando, where he has touted the administration’s positions against abortion and in defense of religious liberty.

Republican recruitment

Middle-class and evangelical Puerto Ricans are by no means all Republicans. But the expectation of Puerto Rican Republicans and of the Trump campaign is that they’ll vote for Republicans at higher rates than will working-class migrants or nonevangelicals.

Still, the Republican recruitment strategy is questionable for several reasons. I’ll name just two.

First, given the devastating toll of the coronavirus in both human and financial terms, it’s hardly certain that a divide-and-conquer strategy that distinguishes between the economic interests of middle-class and working-class Hispanics will succeed as it has in the past. Knowing this, the Latinos for Trump campaign now highlights cultural issues, such as the Goya boycott and the ghosts of socialism’s past. But it is doubtful that Hispanic voters, including Puerto Ricans, will accept their conflation of Biden and Che Guevara.

Related: For this Latina artist in New York, goodbye to all that Goya

Second, in the long run, Republicans will have to find a strategy for recruiting Hispanics in Florida and elsewhere that doesn’t rely on picking off a few thousand or even a hundred thousand votes here and there. So far, it has sometimes helped Republicans achieve narrow electoral victories. But winning 30% or even 40% of the Hispanic vote will become less effective as Hispanics represent a greater share of the populations of Florida and the United States overall.

This is a lesson for Democrats, too. Microtargeting Hispanic communities in particular places, like Puerto Ricans in central Florida, has become the favored approach — because different groups have specific accents, pop icons, favorite dishes or pet policy issues. But it encourages the misguided notion that Hispanics are isolated communities with particular concerns living in pockets of the United States.

Instead, they’re Americans who’ve shaped the United States since the beginning, they share many concerns in common with other Americans, and they’ve settled all across the country. After the election, we should do more to integrate Hispanics into national conversations about the economy, health care, education, immigration and other issues.

But for the next seven weeks until Nov. 3, they’ll continue to focus on particular groups in particular places, like Puerto Ricans in central Florida.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?