A man from Venezuela who migrated to Colombia wears a face mask and carries a mattress at a makeshift camp amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, in Bogotá, Colombia, June 8, 2020.

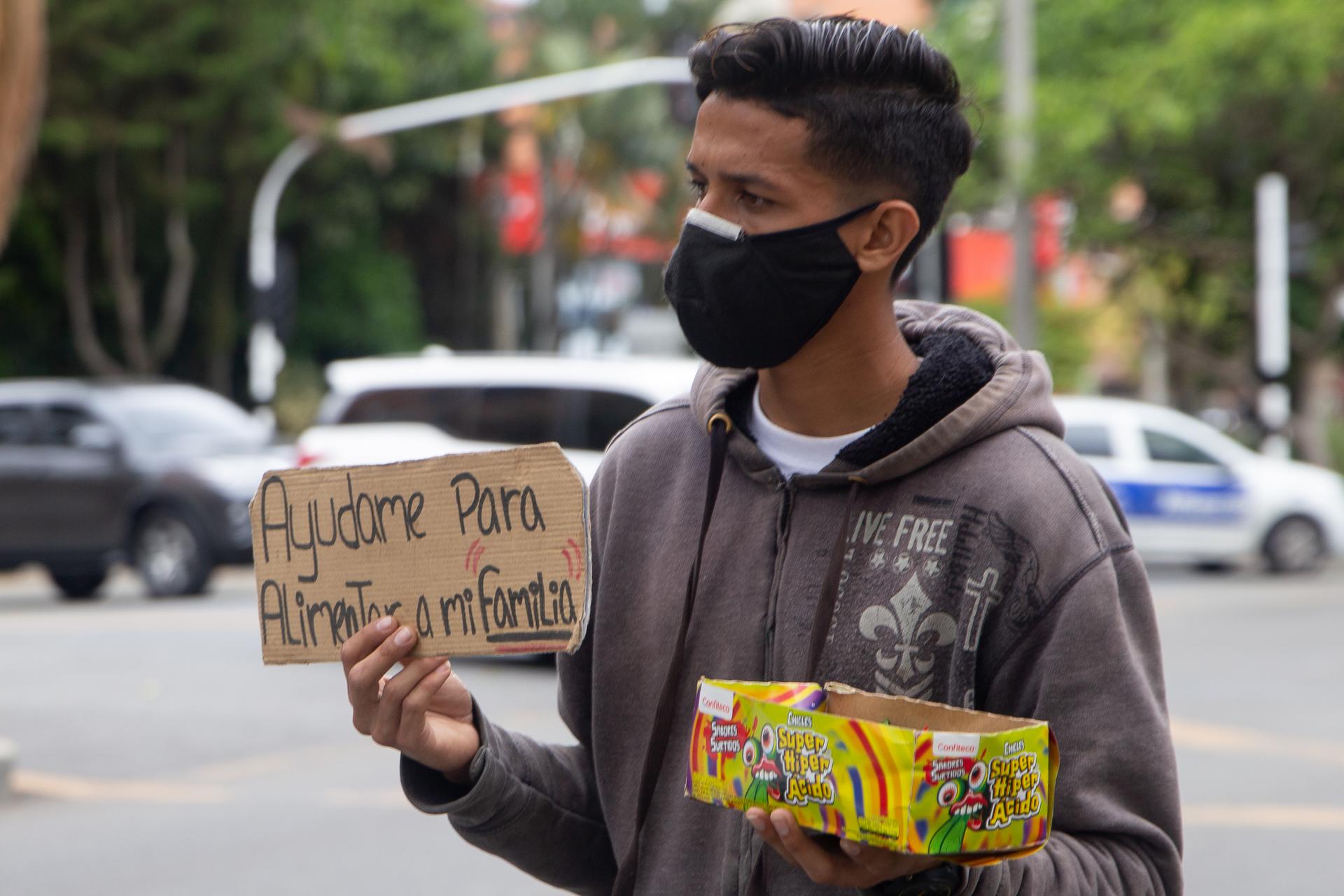

Miguel Benites walked along lanes of cars in Medellín, Colombia, with a black mask wrapped around his jaw. In one hand he held a box of candies and in the other, he held a sign that read: “Ayúdame para alimentar a mi familia. Busco empleo.” (“Help me feed my family. I’m looking for work.”)

Benites, 24, is among the 5 million Venezuelans who have fled their collapsing country in recent years. In Medellín, he found a job as a mechanic and a respite from years of violence and economic turmoil.

But in March, Benites lost that economic lifeline when Colombia went under a now monthslong quarantine.

COVID-19 has left Venezuelans across Latin America reeling and with dwindling options at the same moment that the World Health Organization declared the region the new epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

Colombia has an underdeveloped medical system, dense urban cities and high poverty rates, but its strict quarantine measures have so far helped to avoid the spiking death tolls seen in Brazil and Mexico. As of June 16, it has reported more than 53,000 confirmed cases and over 1,700 deaths, though cases have jumped as restrictions have loosened.

Related: Coronavirus spread threatens Colombia’s Amazonian Indigenous region

But the lockdown also pushed poorer populations to the brink, forcing workers like Benites to decide whether to go hungry or risk infection.

“Right now, well, I’m in the streets trying to survive. … But it’s really hard. Here at the streetlight, you don’t earn a lot, just enough to eat for the day.”

“Right now, well, I’m in the streets trying to survive,” Benites said. “But it’s really hard. Here at the streetlight, you don’t earn a lot, just enough to eat for the day.”

On a good day, he can earn about $7. On a bad one, less than $3.

Related: Meet the woman who buries forgotten migrants from Venezuela

The situation has forced nearly 75,000 Venezuelans to return to the country they once fled, including 22-year-old Danny Quintero Velásquez.

“My fear at the beginning of the coronavirus was something like, ‘Wow, I’m far from home, and if something happens to me, who is going to be with me? No one. I’m alone.’ So, I said it’s better to return to my country.”

“My fear at the beginning of the coronavirus was something like, ‘Wow, I’m far from home, and if something happens to me, who is going to be with me? No one. I’m alone,'” Quintero Velásquez said. “So, I said it’s better to return to my country.”

Quintero Velásquez was among the first wave of people to return by a bus organized by the Colombian government after living for three years in Colombia, host to the largest number of Venezuelan migrants in the region. Others walked hundreds of miles on foot.

Overlapping humanitarian crises have plagued Venezuela for years as economic and political turmoil has spurred on violence, starvation and a collapse of the medical system.

Quintero Velásquez’s heart ached for his home in the northern city of Valencia, and the family he left behind to support. But when he tried to return, he described the process as “torture.”

He first waited for days on the streets in the Venezuelan border city of San Antonio del Táchira without shelter from the blistering desert sun and rain. Later, Venezuelan authorities packed them into a broken-down building with throngs of other migrants to quarantine for two weeks. Reports show that those who resisted were beaten or disappeared.

They lived in deteriorated conditions, he told The World, sleeping on cement floors and eating little more than corn-based arepas. As he waited, he said people along the border called him a traitor and discriminated against him for leaving the country.

This comes despite the fact that embattled Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro said on state TV that all returnees should be greeted “with love, affection and all preventative measures.”

“The experience was horrible for us returning after so much time. … Almost three years of being gone, and to return and be treated like that in your own country, that’s really hard.”

“The experience was horrible for us returning after so much time,” Quintero Velásquez said. “Almost three years of being gone, and to return and be treated like that in your own country, that’s really hard.”

That’s the experience for a growing number of returnees, said Arles Pereda, president of Colony of Venezuelans in Colombia. Since the beginning of the mass migration in 2016, the organization has provided aid and legal resources to many of the 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants in Colombia.

Now, he said their role has been flipped. In addition to delivering food to starving families in Medellín, they’ve “become a bridge” for people who want to return.

“They arrived here with a dream, which many fulfilled — some were in the process of establishing themselves, others were just starting and were very unstable — but many of those dreams have been broken.”

“They arrived here with a dream, which many fulfilled — some were in the process of establishing themselves, others were just starting and were very unstable — but many of those dreams have been broken,” Pereda said.

It’s a struggle not just in Colombia, but for migrants across South America in countries like Peru, Ecuador, Chile and Argentina.

Thousands more wait in informal camps near borders, highways and bus stations across the region, hoping to return home as COVID-19 cases and deaths jump.

According to Colombia’s migration authorities, the Venezuelan government currently only allows 400 migrants to cross back into the country three days a week — leaving them in limbo. There are at least 24,000 Venezuelans in Colombia waiting to return, according to those authorities, and with these restrictions, it could take up to six months for people to return.

Pereda and other human rights leaders fear for migrants returning home, where the medical system was already shattered by years of crisis.

While Venezuela has only reported 3,062 confirmed cases and 26 deaths as of June 16, the country lacks reliable testing and transparency. The real number is likely far higher, and researchers have reported that case counts appear inconsistent with the scale of the pandemic.

Maduro’s government has largely censored journalists and medical workers, but one May survey reported that 62% of hospitals faced shortages of face masks and 90% faced shortages of alcoholic gel.

Human Rights Watch and the Johns Hopkins University officials called the country “grossly unprepared” to take on the brunt of the pandemic, even warning that the deepening crisis there may drive a new wave of emigration down the line.

Now in quarantine with his family in Valencia, Quintero Velásquez feels torn. That looming sense of insecurity he felt in Colombia — that he could get kicked out of his apartment or be infected without any lifeline — is gone. But this has been replaced by dread for the future — something he’s reminded of on a daily basis.

Severe gasoline shortages have created days long lines to buy gasoline at skyrocketing prices, a product that used to be so cheap it was once smuggled over the border and sold in plastic bottles. Access to medical services is practically nonexistent, he said.

Related: Doctors wait hours to fill tanks as Venezuela faces fuel shortages

In May, when they rushed his mother to the hospital for a heart attack, medical staff sent her home because they were only treating COVID-19 patients. Instead of treatment by a doctor, Quintero Velásquez bought her medicine on the black market.

“Is the crisis going to get worse? Yes. It gets worse every day,” he said. “It’s already collapsed because of the gasoline. We’re a petroleum country, and we don’t even have combustibles. … What’s more, the medical system has also already collapsed, and now that’s worsening too.”

He paused and added, “so, thank God there haven’t been that many cases.”