After cops seize a large stash of narcotics, they’ll usually splay them on a table for the cameras. If the bust is really huge — say, a ton of coke or meth — they might pile it against a wall and pose with assault rifles.

But a recent bust on the Myanmar-China border was too massive to fit inside any room. The police had to spread out their haul in a pasture.

“When they put it on display, it was like a football field full of chemicals and equipment.”

“When they put it on display, it was like a football field full of chemicals and equipment,” said Jeremy Douglas, who is the regional representative of the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) for Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

“It is by far,” he said, “the largest amount of meth ever seized.”

Related: A US-style drug war brings a terrible cost: Thai prisons packed full of women

The seizure netted 18 tons of meth, mostly in the form of tiny pink pills, nearly 200 million of them stuffed into bulging sacks.

Myanmar’s police also showed off stainless steel tanks, gleaming reactor vessels, big glass flasks — everything needed to run a “Breaking Bad”-caliber superlab.

Plus, barrels of chemicals, almost too many to capture in a single photo. This included drums filled with a super-potent type of fentanyl — called methyl fentanyl — that may be as much as 200 times more powerful than heroin.

There were roughly 1,000 gallons of the stuff, enough to fill about 25 bathtubs, and get millions of people high. Investigators still don’t know where it was headed: possibly around Southeast Asia, to cities such as Sydney or Seoul or even to North America.

Related: Thailand approves medical pot in small step away from US-backed drug war

As the UN put it, this was “one of the largest and most successful counternarcotics operations” in Asia’s history. Myanmar’s army and police, which conducted the raids, are naturally pleased.

But the story behind the raid is quite messy — one involving double-crossing traffickers, Chinese mafia and even the White House.

The operation targeted a string of warehouses and refineries in the northern hills of Myanmar, namely an area known as Kutkai. The superlabs were very sophisticated, Douglas said, “like mini-factories you’d see in an industrial park.”

How could a gigantic narcotics enterprise thrive there in secret?

Well, it didn’t.

Myanmar’s government has known about the labs for years. The same goes for the United States’ Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and Chinese intelligence. Even The World knew it was there, writing in 2015 that the area contains “a number of heroin and meth refineries.”

Related: Thailand is betting big on cannabis. Visit its first legal lab.

The labs went undisturbed because they were protected by a militia — one that happens to serve under Myanmar’s army.

Called Kaung Kha, it is technically known as a “people’s militia force.” Its troops wear uniforms and tote machine guns. Their mission is to defend a patch of land against the army’s arch foes: Indigenous rebels fighting to gain control of their Native lands.

The militia actually fends off these rebels for free, receiving almost nothing from the government: no bullets, no weapons, no rice to feed their ranks.

But there is a big caveat, says Khuensai Jaiyen, a scholar with the Pyidaungsu Institute, which monitors Myanmar’s armed groups.

“It’s a paramilitary group, set up by the government. Their main job is to fight off the army’s opponents. But as long as they do that, they get a free hand to engage in all sorts of economic activities.”

“It’s a paramilitary group, set up by the government,” he said. “Their main job is to fight off the army’s opponents. But as long as they do that, they get a free hand to engage in all sorts of economic activities.”

In that region, no economic activity is as lucrative as the meth trade. Asia’s meth economy is valued by the UN at roughly $60 billion — and northern Myanmar is its heartland.

“It’s not a written policy,” Khuensai said, “but the military cannot afford to feed, arm and equip them. So, they get to work that out by themselves,” usually by relying on drug profits.

Khuensai was once secretary to a man described by the US as the world’s largest heroin producer — a commander named Khun Sa whose opium-producing army controlled a large chunk of Myanmar.

Khun Sa insisted he was liberating Indigenous people from oppressive army rule. The DEA, in the mid-1990s, countered that “he has delivered as much evil to this world as any mafia don has done in our history.”

For long stretches of his narcotics career, Khun Sa would forego rebellion and actually cut deals with the army, Khuensai says.

He’d promise to keep communists or rebels from overrunning a swath of the country. In return, the government would leave his poppy farms alone. Many militias in Myanmar’s borderlands, Khuensai says, still work under the same arrangement to this day.

Related: They were CIA-backed Chinese rebels. Now you’re invited to their once-secret hideaway.

But what many fail to understand, he says, is that the jungle commanders are not the biggest profiteers.

There are no chemistry grads among the militias’ rank and file. Nor do local guerrillas have the right international connections to smuggle kilos around the world.

So, they will invite outside “investors” — inevitably Chinese mafia, Khuensai says — to come and build the labs. The mafia imports the chemists, operates the refinery and traffics the drugs to wealthier countries such as Australia or Japan.

“When Khun Sa was working with the military, the investors would come and set up refineries. They came to him because his area was safe from disturbance. It lasted until he declared independence.”

“When Khun Sa was working with the military, the investors would come and set up refineries. They came to him because his area was safe from disturbance,” he said. “It lasted until he declared independence,” which voided that pact with the army.

Was that the fate of the Kaung Kha militia, which saw its superlabs gutted and scattered across a field for the world to see?

Perhaps.

The armed group had no interest in independence. But it is believed by many, Khuensai says, that they had secretly supplied kilos of meth to rebels loathed by the army. Other rebel groups have described this as a conspiracy theory, but, regardless, helping enemies of the state finance their insurgency with drugs would certainly break the protection deal.

“If you’re working for the military, you can do anything,” Khuensai said. “But if you’re working for their enemies, it’ll be something else. That could be the reason for their downfall.”

The mountain of meth stacked up by Myanmar’s authorities after the raid proved startling — even to Douglas, the UNODC official. But now, his top concern is figuring out what traffickers planned to do with all that methyl fentanyl.

Related: Can Asia’s largest armed group fend off coronavirus?

Fentanyl is a household name in America, where opioids kill more people than car wrecks. Yet, many cops around Southeast Asia have never even heard of the drug.

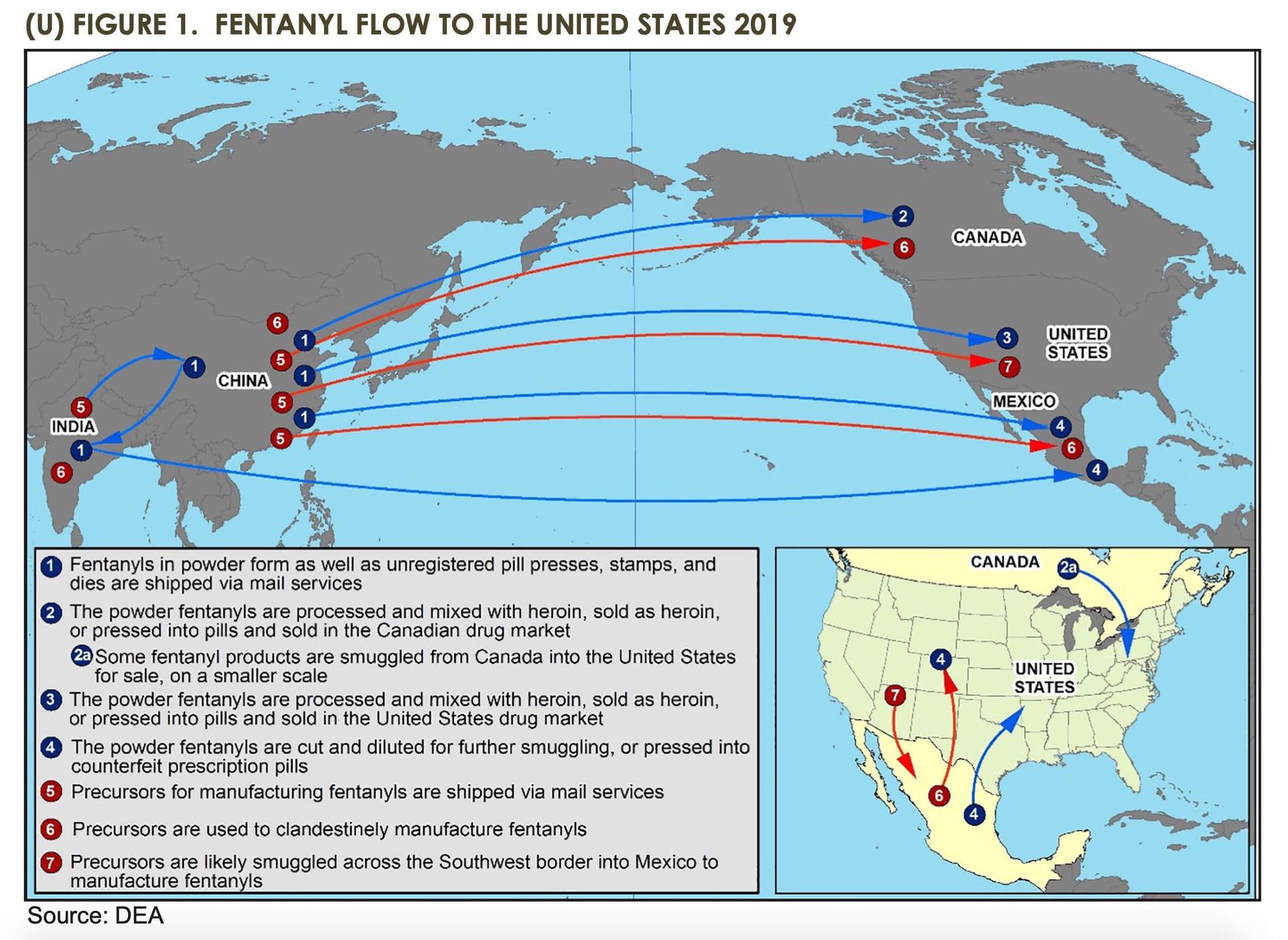

It is infamously churned out of factories in China, but usually shipped straight to America, which has the biggest appetite for fentanyl. Very little is diverted into the Asian nations in China’s backyard.

After the raids, Myanmar’s authorities shared their findings with Douglas, who is based in Bangkok. The sheer volume of the fentanyl took him aback. It was almost too much, he thought, to sell within the Asian market.

Just to be sure, his office asked Myanmar officials to test the chemicals again. They did, a total of three times.

Each time, the results came back the same: methyl fentanyl. It is “a more powerful version of fentanyl, which is already 50 times more powerful than heroin,” Douglas said.

“This variant,” he said, “might actually be [200 to 300] times the strength of heroin.” Travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have so far prevented UN personnel from flying in to precisely identify the potency of the liquid.

It’s unlikely the drug was synthesized in Myanmar. The seized lab equipment was suited to cooking meth, not fentanyl. That means it was likely smuggled over from a factory in China, which has more chemical-producing factories than anywhere on Earth.

Related: Coronavirus fears in Asia create a black market for masks

No matter where it was brewed up, Myanmar is a fantastic place to store and traffic narcotics. For decades, crime syndicates have pushed drugs along jungle trails and into neighboring Thailand, home to some of Asia’s biggest ports, which ship to countries all around the world.

The goal of any drug trafficker is to get their commodity from the lab — inevitably hidden away in some remote place — to a bustling city full of potential customers.

The markup is boggling. For example, a kilo of crystal meth will sell for roughly $5,000 in a militia-run patch of Myanmar. But it can go for more than $200,000, Douglas says, if smuggled into Australia or Japan.

At present, there is no major fentanyl pipeline running through Myanmar to the United States, the largest market for fentanyl buyers on Earth. But traffickers would be hugely incentivized to create one, Douglas says.

“China went after fentanyl — and they did it very effectively and very quickly.”

Especially since the traditional route from China is under siege by Beijing.

About two years ago, he said, “China went after fentanyl — and they did it very effectively and very quickly.”

US President Donald Trump had been pushing them to do just that. He has told President Xi Jinping that resolving their trade war may hinge on Beijing choking off the flow of fentanyl to America — and China has taken action.

“President Xi, in a wonderful humanitarian gesture,” the White House stated, “has agreed to designate fentanyl as a controlled substance, meaning that people selling fentanyl to the United States will be subject to China’s maximum penalty under the law.”

But Douglas believes the crackdown in China may be pushing fentanyl out of China’s backdoor and into the “highly unregulated environment” of Myanmar’s borderlands.

From there, he said, “it’s reasonable to assume that Southeast Asia, with its very good logistics … could very quickly become a source for North America.”

Southeast Asia already supplies tons of cheap food, gadgets and other goods that underpin middle-class lifestyles in America — and it does so through fleets of US-bound ships that leave the tropics every day. It would not be too hard to hide fentanyl aboard those ships.

“There are lots of ways,” Douglas said, “to bury your product in legitimate trade flows.”

So far, fears that a fentanyl pipeline may soon run from Myanmar to the US is just informed speculation.

Other scenarios could explain why all that methyl fentanyl was being stockpiled in Myanmar. Perhaps it was going to get mixed in with bags of heroin sold around Asia.

But that, too, is a frightening prospect. Fentanyl is far more fatal than meth, the region’s most popular drug. If it grows popular in Southeast Asia, it could bring on the same sort of overdose wave that has sent America reeling.

But if the White House or DEA do decide to turn their gaze to narcotics labs in Myanmar, they might first consider how badly America has failed to suppress the country’s drug trade in the past.

Consider their crusade against Khun Sa. In the 1980s, when his heroin was hitting New York streets, Khun Sa was dubbed the “Prince of Death” by American officials. The US even placed a $2 million bounty on his head.

But unlike Colombia’s Pablo Escobar, Khun Sa was never caught by the DEA or US-backed forces. Instead, in the mid-1990s, the kingpin retired comfortably — and he did so under the army’s protection.

Some of his lieutenants, joining army-linked militias, have carried on the same trade, helping raise the regional drug traffickers’ profits to at least $30 billion.

That’s more than the gross domestic product of some Asian nations — and their earnings are poised to go up further still. The Golden Triangle drug trade grows larger every year.