Giselle Cycowicz, a Holocaust survivor living in Jerusalem, shares her story by phone with a group of high school students on the phone as they visit Auschwitz concentration camp.

Giselle Cycowicz was supposed to spend this year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day in Poland. The 93-year-old Jerusalem resident usually accompanies Israeli high schoolers there to learn about life before the Nazi invasion and under occupation.

“Normally, I would be, this time of the year, I would be in Poland, because I also go to Poland to accompany high school kids and we go to all the sites, many sites of the Shoah,” Cycowicz told The World. “And I talk about the Shoah. I am the, what they call, witness.”

Close to 400,000 survivors of the Shoah, or Holocaust, are believed to still be alive worldwide. About 1.5 million people died at the Auschwitz concentration camp, 90% of them Jews, before the Soviet army liberated the camp on January 27, 1945.

Cycowicz is a survivor of Auschwitz. She was born in the town of Khust, in the Carpathian Mountains. Today, it is part of Ukraine, but at the time it was part of Czechoslovakia. In 1939, Hungary took over the region, and not before long all the Jewish children in the town were expelled from school. Cycowicz was 12 years old at the time.

She didn’t go back to school for another three decades, when, at age 42, she went to college in the United States.

Before the war, Khust had about 20,000 residents, about 8,000 of whom were Jews, mainly working in commerce, said Cycowicz’s daughter, Yael Bier, who shared some of her mother’s recollections with The World. But after the war broke out, there was no livelihood for Jews.

Cycowicz’s father did what he could selling mineral water, and to support themselves, the family offered to host overflows of guests at local inns. The children — Cycowicz was the youngest of three daughters — would find empty corners of the house to sleep in as they hosted tourists.

But life for Cycowicz’s family was unraveling. From a comfortable home and good jobs, things became very difficult.

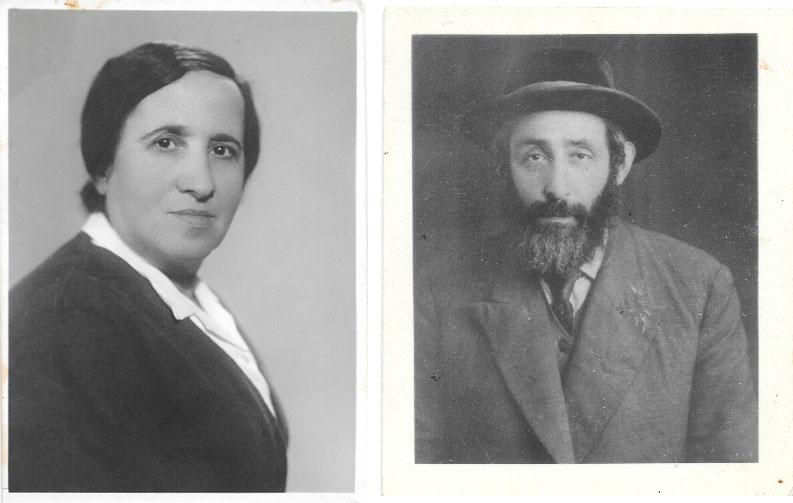

In March of 1944, the Nazis marched into Hungary. Within three months, all Jews were sent to the ghettos. Five weeks later, Cycowicz’s entire family was sent to Auschwitz by train. She remembers her father, Wolf Friedman, telling them, “Be sure to make yourself useful. That’s how you will survive.”

“Always on my mind is my parents. My father worked for five months in coal mines on 200 grams of bread a day. That was the entire food other than soup, which was water with some weeds. And when they were brought back to Auschwitz, to Birkenau, his face was all black, because they didn’t have a chance to wash, and he was a skeleton without any flesh on his bones.”

“Always on my mind is my parents,” Cycowicz said. “My father worked for five months in coal mines on 200 grams of bread a day. That was the entire food other than soup, which was water with some weeds. And when they were brought back to Auschwitz, to Birkenau, his face was all black, because they didn’t have a chance to wash, and he was a skeleton without any flesh on his bones.”

She said a person from their town said, “Today, 200 Jewish men were brought back to Auschwitz from the coal mines where they worked … Tomorrow, we won’t be here anymore.”

After that, Friedman was sent to the gas chambers.

“He was 49 years old. And he knew all along. This is my biggest pain, that they know that they’re going to be killed by gas,” Cycowicz said. “Can you imagine this? We know that something like this exists and that it may happen at any moment in Auschwitz, that they should take us and put this into the gas chamber. But it wasn’t imminent. We didn’t know for sure. But they know, we are now going to go into the gas chambers and be killed.”

Cycowicz was in Auschwitz for six months with one of her sisters and mother, Hanna Friedman, who was 50 years old, and frail. Keeping their mother alive became their purpose, Bier said.

One day, Cycowicz saw that hundreds of adult women in the camp were sent to a storage building — her mother, Hanna, among them. After a few hours they were all led out of the building and marched out of the camp, but Cycowicz’s mother wasn’t with them. Once the coast was clear, she and her sister entered the building and found their mother hiding behind a cabinet. Hanna told them she grabbed another woman to try and hide her as well, but that woman resisted and said she didn’t want to be beaten before being killed. Cycowicz later learned that the women were sent to a labor camp where her mother surely would not have survived.

Later, Cycowicz, her sister and mother were sent to a different camp, where they remained until their liberation. One day, the camp’s Nazi armed officers, the SS, lined them up and told them: “We’re waiting for the Russians. You can go wherever you want, but please don’t do anything to us.”

After liberation Cycowicz’s family moved to the US, where she became a psychologist. She married and had three children in the US. In 1992, after her husband died, she followed her children who had already immigrated to Israel.

Cycowicz joined an organization called Amcha, which provides social and psychological support for Holocaust survivors. She says she has found new meaning in that.

“I’ve been living alone. And it’s fine for me. I am very active. I’ve been working. I’m still on a payroll. I still have patients and I have now in this week, from the beginning of the holidays, I’ve had maybe 200 telephone calls,” she said. This year’s Passover holidays end Thursday.

“Every minute of the day somebody calls to say, to wish a good holiday, and to remember the Shoah, and to wish me good health. So I’m not alone. And I talk to the children a few times today. And I have, thank God, 21 grandchildren and a large number of great-grandchildren. So I don’t feel alone.”

![]()