From cow pox to mumps: people have always had a problem with vaccination

Edward Jenner, vaccinating his young child, held by Mrs. Jenner; a maid rolls up her sleeve, a man stands outside holding a cow. Coloured engraving by C. Manigaud after E Hamman.

A recent surge in mumps among young adults in the UK has been linked to the 1998 MMR vaccine scare, when a now-discredited medical paper authored by Andrew Wakefield suggested a connection between the vaccine and the development of autism. The publication of the paper led many parents to refuse the vaccine for their child.

The effect of Wakefield’s paper is still deeply felt. Indeed, every week seems to bring news of an unfolding controversy about vaccination. In the UK an alarming decline in childhood vaccination rates has been recorded. Vaccine scepticism seems to be increasing — a fitting testament to these troubling times, when distrust of science and expertise permeate.

Social media is often pinpointed as part of the problem. The ease with which ideas and information about vaccination are spread on Twitter, Facebook and other platforms is causing concern. As one medical journalist observed in 2019: “Lies spread through social media have helped demonise one of the safest and most effective interventions in the history of medicine.”

Social media has undoubtedly changed the way information about vaccination is engaged with. But the media-driven nature of the debate isn’t actually that new. When vaccination began at the end of the 18th century, it quickly became fodder for commentators.

Related: Banning travel is not the best way to contain the coronavirus, Ebola expert says

In the 1790s, the surgeon Edward Jenner had confirmed through a number of experimental procedures on patients that exposure to cowpox pustules — symptoms of a disease of cows’ udders which in humans resembles mild smallpox — could confer immunity to smallpox. Following the publication of his results in 1798, vaccination came into widespread use.

With it came immediate unease and distrust. Satirists like James Gillray capitalised upon rumours that inserting cowpox pustules into the skin might cause one to sprout cow horns, a fear which had its roots in religious and cultural stigma surrounding the pollution of blood with animal matter.

Images like Gillray’s were an early indicator of the ability of vaccination to capture the public imagination in a way few other medical developments would over the ensuing decades. This only intensified in the mid-19th century, when the Compulsory Vaccination Act of 1853 decreed that all babies should be vaccinated. Compulsory vaccination aroused accusations that personal liberty was under threat. In its wake, resistance to vaccination ramped up considerably.

Related: The top issue for one Arizona first-time voter? Health care.

Victorian vaccination

Vaccine hesitancy was amplified by the tumultuous world of print which characterized the Victorian age.

Improved printing technologies and lower prices gave rise to a rapid increase in the number of periodicals and newspapers available. Information was democratized, as cheap papers and periodicals became accessible to women and the working classes. Medical and health issues were mined by journalists for their dramatic content, and tropes of the vaccination debate we see today were given shape by the information revolution of the late 19th century.

Indeed, it was during this time that the polarisation between “pro” and “anti” vaccination camps solidified. Use of the phrase “anti-vaccination” rocketed at the end of the 19th century. Pamphlets and magazines sprung up in opposition to its use, claiming that vaccination was a dangerous, toxic procedure that was being thrust upon society’s most vulnerable citizens: children.

The not so catchily named National Anti-Compulsory-Vaccination Reporter, a magazine which began in 1876, sold hundreds of copies every month. The paper revelled in its radicalism, its opening editorial announcing: “As sound-hearted and enlightened Anti-Vaccinators, it is our bounden duty, and should be our steady and constant aim, to work towards the complete destruction of Medical Despotism.”

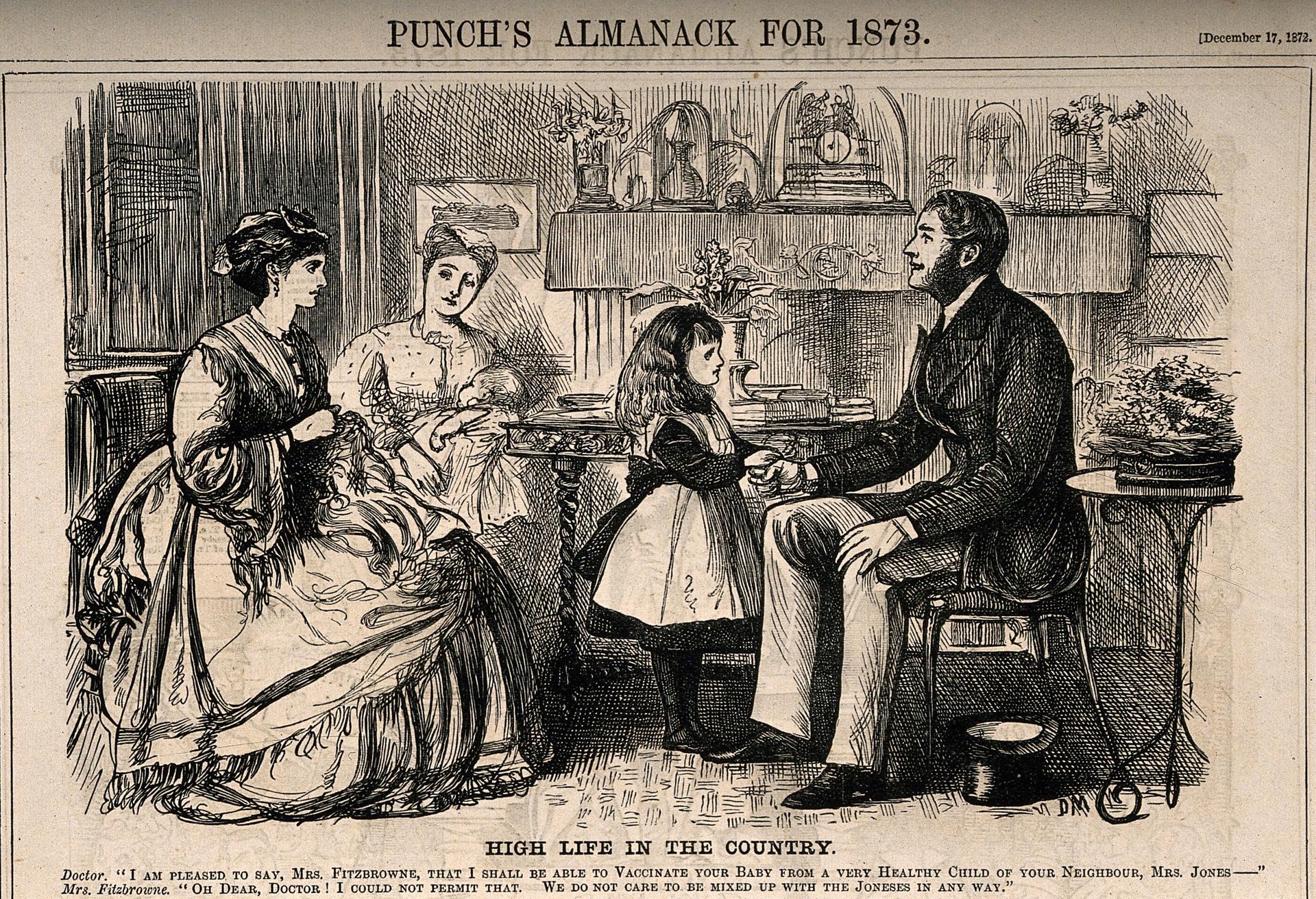

Meanwhile, humour publications such as Punch and Moonshine skewered organisations like the Anti-Vaccination League for their zealotry and irrationality. In an of age of self-professed scientific medicine, the movement’s association with radical religious beliefs and other non-conforming lifestyle choices, such as vegetarianism and abstinence from alcohol, made it a target for lampoonery.

A polarised debate

Anti-vaccination publications believed they were deliberately excluded from a press that was in the pocket of the state and who sought to suppress the true dangers of vaccination. Publications such as The Times had become the gatekeepers of public opinion — in 1887 the paper claimed to have suffered from “an epidemic of letters about vaccination.” But anti-vaccinators lambasted newspaper editors as “shamelessly unprincipled and venal” for refusing to publish that correspondence which was critical of vaccination.

Related: What we know and don’t know about COVID-19

This is an accusation that has its echoes in conspiracy theories that continue today. The prominent American anti-vaccine organisation Children’s Health Defense has denounced the mainstream media for being under the thumb of Big Pharma and ignoring the voices of those harmed by vaccines.

As this shows, there has always been a potency to the vaccination debate few other medical practices generate. The provocative issue of children’s health at the heart of it, and the tension vaccination evokes between notions of collective responsibility and the freedom to choose what we think best for our bodies has made it an emotive, highly polarised debate that has been brewing since the 19th century. This has always been galvanised by sustained media interest.

But there is a complexity to vaccination that polarisation does not properly unpack. What of, for example, the many people who would not identify as “anti-vax,” but instead form a loose group who are hesitant about vaccines and may delay or choose only some vaccinations?

Social media may amplify division between the two camps, but it builds upon a long history of media outlets constructing it.![]()

Sally Frampton, Humanities and Healthcare Fellow, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?