Lake Erie turns toxic every summer. Officials aren’t cracking down on the source.

A boat cuts through pea-green cyanobacteria, often known as harmful algae, choking western Lake Erie in Ohio, Aug. 5, 2019.

This story is part of a series by the Center for Public Integrity, Grist and The World about how our overuse of fertilizer harms the climate and endangers the public.

It was sunny and 82 degrees, a perfect August day for a trip to the public beach just outside Toledo. But hardly anyone was here. And no one was swimming. “DANGER,” warned a red sign posted in the sand near the edge of Lake Erie. “Avoid all contact with the water.”

The reason: The water was contaminated with algae-like cyanobacteria, which can produce toxins that sicken people and kill pets. This is the noxious goo that cut off about 500,000 Toledo-area residents from their tap water for three days in 2014 and made at least 110 people ill.

It suddenly seems like harmful algae blooms are everywhere. In some cases, they’re hard to miss, forming a colorful layer of muck on waterways; in others, they lurk below the surface, fortifying themselves before bursting back into view.

Hazardous algae scuttled swimming at Mississippi’s mainland beaches on the Gulf of Mexico for most of the last summer. They killed dozens of dolphins and hurt tourist-dependent businesses in Florida over a 16-month stretch that finally ended in February 2019. Scientists suspect they’re causing clusters of deadly liver disease across the country. In rare cases, they’ve killed people shortly after contact.

Related: Farming’s growing problem

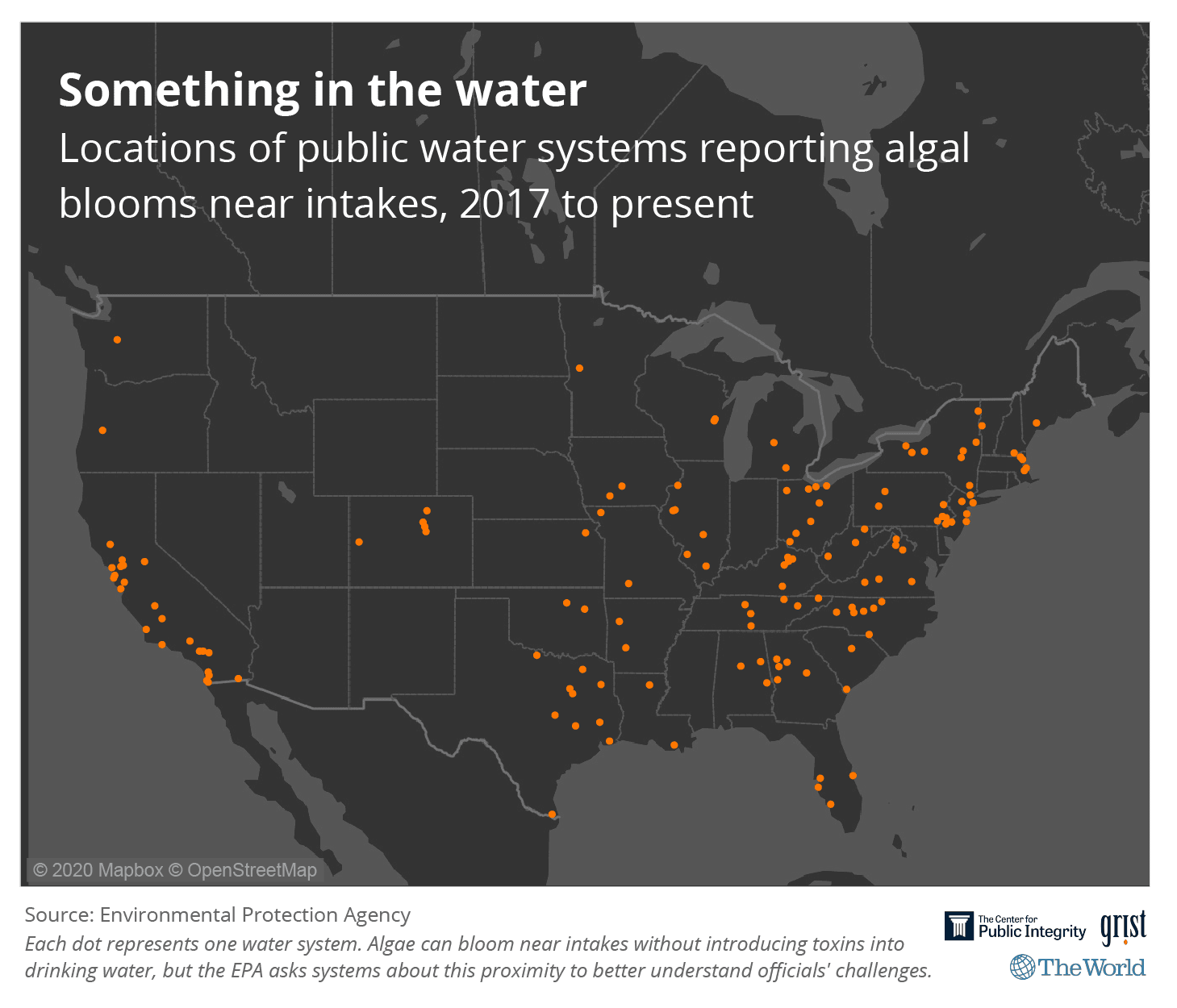

Even as toxic algae triggered no-drink orders in at least three more communities in 2018, data from the US Environmental Protection Agency shows just how much worse the problem could get: Nearly 150 public water systems in 33 states have reported spotting algae blooms near their intakes in reservoirs or other water sources since 2017, in many cases multiple times, according to an analysis by the Center for Public Integrity, Grist and The World.

The algae are natural. This slow-motion crisis, however, is largely manmade — and neither the federal government nor states are effectively cracking down on the major contributor.

Harmful blooms like cyanobacteria or the so-called red tide grow out of control when they’re overfed nutrients such as phosphorus. That’s exactly what commercial fertilizer and manure running off farm fields provide. US rules intended to protect people from water pollution have prompted sharp reductions in the nutrients discharged by sewage treatment plants since the 1970s, but loopholes in the Clean Water Act shield agricultural operations from similar federal enforcement.

States have broader leeway to act. But they have largely opted to make recommendations about farming practices and promote voluntary measures that don’t draw opposition from influential agricultural trade groups.

After Toledo’s water crisis, Ohio went further, passing a law that prohibits farms in the western Lake Erie region from applying fertilizer on frozen or rain-saturated soil. But here, too, most fertilizer runoff efforts are voluntary — and exceptions undercut the state’s 2015 ban.

Related: Africa’s producing more fertilizer, but it’s still not getting to all farmers

More than a dozen years have passed since Ohio convened a task force to figure out how to tackle its Lake Erie problem. Since 2011, the state has spent more than $3 billion on it, largely to upgrade sewage and drinking water plants. But Ohio’s agriculture nutrient-reduction strategy has yet to show results.

“Everything we’ve done so far, trying to reach these reductions voluntarily, has had no impact,” said Jeff Reutter, a longtime Lake Erie researcher who retired from the Ohio State University in 2017. “The voluntary approach has been — I guess you’d say — a total failure.”

The state could set legally enforceable limits on nutrients in Lake Erie. It hasn’t. Two groups and a local county are suing the EPA, arguing that it has a duty to make Ohio officials act.

The state also could mandate that farmers not use more fertilizer than their crops need. It hasn’t done that, either. It barely tracks the issue. Little information about how much farms fertilize is publicly available beyond some documentation from operations raising large numbers of animals, such as several thousand or more pigs.

Dozens of such sites, producing more than 760 million gallons of phosphorus-rich manure each year that they must do something with, are in the region that drains into western Lake Erie. An analysis by Public Integrity and its partners of Ohio Department of Agriculture permits for those farms found widespread application of manure to land that the farms’ own soil tests show already had more than enough phosphorus for key crops. That increases the odds of nutrients leaving the fields to fuel harmful algae.

More than 40% of the acres disclosed by the farms had phosphorus levels that, according to field research by the Ohio State University, is plenty to grow the state’s major crops for at least five years. Harold Watters, an agronomic systems field specialist at the university and a farmer himself, has a one-word fertilizing recommendation for acreage with those phosphorus levels: “Stop.”

But that’s all it is. A recommendation.

The Ohio Department of Agriculture, which has the dual mission of overseeing farm rules and creating economic opportunities for the industry, would not make its director available for an interview. In written answers to questions, the agency called its rules effective and said that limiting phosphorus to the amount crops need would needlessly restrict manure application “in places where risk of [phosphorus] loss is low.”

“There is remarkable progress being made in the efforts to improve water quality in Ohio,” the agency said in its statement. “It is a priority for Governor Mike DeWine, with dedicated funding through the legislature and an unprecedented collaboration between the agricultural, conservation and research communities.”

The state’s newest approach, announced in November, is to pay farmers to use a customized combination of anti-runoff strategies, such as injecting fertilizer into the soil rather than spreading it on top.

“Ohio has supported many programs to help farmers reduce nutrient loss over the years, but the state hasn’t done nearly enough, nor have previous plans focused enough, on reducing phosphorus runoff from agriculture,” DeWine, a Republican, said in a statement about the “H2Ohio” plan. “That changes now.”

H2Ohio doesn’t require any of these farming practices, though. It encourages them by offering subsidies.

Containing the algae problem is only going to get harder, scientists warn. Heavier rain, courtesy of a warming world, means more nutrient runoff. Research from Stanford and Princeton predicts that government agencies will have to double down on control efforts to keep up. And because nutrient pollution causes water bodies to emit more of a potent climate-warming gas — in part, it appears, because of the cyanobacteria themselves — there’s a dangerous vicious cycle at work.

If officials can’t stop it, the consequences will mount in serious and unexpected ways.

“I had to file bankruptcy,” said Steve Klosterman, whose business developing lots and building homes alongside Ohio’s Grand Lake St. Marys unraveled after severe algal blooms destabilized that market, about 90 miles southwest of Toledo. “I had 10 employees, and now I don’t have any. It’s just me. I basically lost everything.”

‘We’re paying’

Up on the projector screen was a photo of a glass full of what looked like pea soup: the cyanobacteria that temporarily cut Toledoans off from their public water. Mike Ferner, giving a presentation in August to retired locals at the West Toledo YMCA, reminded them that this happened five years earlier “and some people” — he meant state officials — “are still looking for solutions.”

He popped up a different photo to illustrate that: A person with their head in the sand.

Ferner, a retired union organizer and former Toledo councilman, runs the all-volunteer Advocates for a Clean Lake Erie. He’s among the Toledo-area activists who think the solution is obvious: Stop approving more animal feeding operations in the region and require more of the ones already there.

Ohio has fewer farms now than it did 30 years ago, when the lake was healthy, but they’re raising more animals. The number has quadrupled at the average hog operation, for instance. Since 2015, the state issued permits for nine new sites with 4,500 cows, 35,950 hogs and 2.6 million chickens between them in the western Lake Erie region, according to an analysis by Public Integrity and its partners. Other area sites already in operation added more than 700,000 animals, mostly chickens. Officials are considering proposals to build sites for nearly 30,000 additional hogs.

There’s simply too much manure now concentrated in small areas, environmental advocates argue — a problem the EPA noted in a 2012 report about the water-quality consequences of “the industrialization of livestock production in the US.”

“These animal-factory owners, they’re doing what every industry has done through history — they’re trying to shift the cost of their production onto somebody else,” Ferner told the retirees. “And that’s what’s happened. We’re paying to clean up their pollution.”

Kevin Elder, a consultant for the Ohio Pork Council and other agriculture commodity groups, said the phosphorus escaping from farms is a collective problem but comes to “a very small amount per acre” of about two pounds per year — though that’s an average and can vary a lot.

“I don’t think the manure is any more [to blame] than the commercial fertilizer,” said Elder, who ran livestock environmental permitting for the state before retiring to work with the industry he used to oversee. “I think there’s probably better regulations, hard regulations, on the manure.”

The state requires farmers and brokers handling large amounts of manure to get certified and keep records on site. But actual restrictions are thin. The analysis of permit records by Public Integrity and its partners shows the results: Many farmers reported plans to add manure to acreage that already had phosphorus levels above the threshold that Ohio State University experts say is plenty for years of bountiful crops — 40 parts per million with the so-called Mehlich III soil test, or 30 parts per million if using an older test.

The state sets no phosphorus cap for most farms. For the rest, typically big operations, it’s high: generally 200 parts per million on a Mehlich scale.

“The rules weren’t written to grow crops, the rules were written to get rid of waste,” said Adam Rissien, author of a 2017 report about manure for the Ohio Environmental Council. “When I said, ‘Let’s lower that,’ [state and industry officials] said, ‘That’s not going to work.’”

Elder, the Ohio Pork Council consultant, says farming is simply too varied for many hard-and-fast rules. Crops such as sweet corn and tomatoes, he said, need more phosphorus than feed corn and soybeans.

In Ohio, though, acres in feed corn and soybeans in 2018 outnumbered all other crops combined by more than 5 to 1. For an operation planting the typical Ohio rotation of crops, there’s no need for phosphorus above 40 parts per million, said Watters, the agronomist. The main debate among experts, he said, is whether it’s OK to push it as far as 50 — way below the current cutoff.

The rule that died

When farm rules do get proposed, they can hit a buzz saw of opposition.

The state’s previous governor, Republican John Kasich, found that out the hard way when he signed an executive order in 2018 telling the Ohio Department of Agriculture to consider categorizing eight watersheds that drain into Lake Erie as “in distress” and establishing nutrient-management requirements for farms there. He said in a statement at the time that “it’s clear that more aggressive action is needed.”

Some environmentalists doubted this approach would be stringent enough to move the needle much, but agriculture groups were outraged. Top members of the Legislature told Kasich to drop it. The head of the agriculture agency opposed it, according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and Kasich fired him. Finally, an agency commission charged with deciding whether to declare the watersheds in distress tabled the measure despite hearing from scientists on the panel that phosphorus levels were not improving and public health required more action.

Adam Sharp, the Ohio Farm Bureau’s executive vice president, summed up the industry’s influence in a 2019 email to members about another Lake Erie battle: “We in agriculture may be small in number but, together with farmers, we are large in force.”

Karl Gebhardt, who ran the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency’s Lake Erie programs during the Kasich administration, watched the 2018 fight with frustration. Gebhardt is a former Ohio Farm Bureau lobbyist. But if voluntary approaches aren’t getting results, he said, “something else has to change.”

“It’s not fair for the farmers … that are doing the right thing, that are implementing the right programs, to have the knucklehead next to them saying, ‘Nah, I’m not going to do it,’” he said.

Advocates for a Clean Lake Erie sees Ohio’s EPA as exactly that sort of knucklehead. The agency wouldn’t declare the algae-choked western Lake Erie “impaired,” the first step in a Clean Water Act process that ends with an enforceable improvement plan, until the group and the Environmental Law & Policy Center sued. Then the Ohio agency signaled that it had no near-term plans to start the next step, setting phosphorus limits. The groups sued again — and this time, Lucas County, in which Toledo is located, joined in.

The case, which like the previous lawsuit was brought against the US EPA because it oversees states’ handling of Clean Water Act requirements, passed a key test in November when a federal judge declined to dismiss it. Ohio contends it is pursuing other measures to help Lake Erie, US District Judge James G. Carr wrote in his order, but the state did not supply “a credible plan” to fix the problem.

Ohio’s EPA would not make anyone available for an interview. But in a statement, the agency wrote that while the region that drains into western Lake Erie does not have a phosphorus limit, dozens of small watersheds within the area do. Advocates believe a limit for the entire region would be more effective, though they expect they will have to dog regulators for follow-up action.

Deep into his presentation at the West Toledo YMCA last summer, Ferner said Ohio could take a lesson from the nutrient-overloaded Chesapeake Bay. Though the bay’s health is far from perfect, and agriculture nutrients remain a challenge, progress accelerated after the US EPA agreed to impose limits, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation says.

Lake Erie, on the other hand? The week Ferner gave his talk, its algae bloom had ballooned to nearly the size of Houston.

Blame it on the rain

Anthony Stateler zipped up the road in a mud-flecked utility terrain vehicle and turned into one of his family’s fields in McComb, Ohio. There, by a ditch, sat a white container full of specialized equipment. He’d just explained how it measures nutrients in the water leaving the field when it interrupted him, making a soft whirring sound. The pump was pulling a sample.

Stateler and his family raise 7,200 pigs at any given time. They use most of the manure to fertilize the corn, soybeans and wheat they grow on about 920 acres, and they sell the rest to other farmers. Ask the Ohio Pork Council about nutrient runoff, and officials there will probably suggest you talk to the Statelers because of their relentless efforts to better understand and contain it.

They’re part of an experiment by the US Department of Agriculture and the Ohio Farm Bureau to test cutting-edge conservation practices that could improve Great Lakes water quality. In addition to the monitoring equipment, they’ve got a phosphorus removal pit with material that traps the nutrient. Water-management gates hold back rainwater, giving it a chance to soak into the soil rather than running out their underground drains and, eventually, into Lake Erie, about 45 miles northeast. They inject manure into the ground, too, which helps keep more nutrients in place.

But the Statelers don’t want these or other practices turned into requirements.

“We don’t have the science behind things yet to make it mandatory,” said Anthony’s father, Duane Stateler, who has been farming in the area for five decades. “And to try to mandate it doesn’t make any difference because [farmers don’t] have the money.”

The way Anthony Stateler sees it, the explanation for Lake Erie’s tipping from good to ill health is heavier rain washing farms’ nutrients away, not anything farmers are doing differently.

More rain, courtesy of climate change, does contribute to runoff problems — and financial trouble for farmers. Last year was especially bad: Extreme weather, the Ohio Department of Agriculture said in a suicide prevention campaign, brought at least some farms “the most devastating economic losses they have ever faced.” Drenchers that dump more than two inches in a 24-hour period are happening about 50% more often in the Great Lakes region these days than in 1960, said Reutter, the Lake Erie researcher.

But the lake’s increasing problems are also a matter of farm-management decisions, scientists and the state’s phosphorus task force report say. For instance: Northwest Ohio farmers use subsurface drains to keep their fields from getting soggy, and they’ve installed large numbers in recent decades, said Laura T. Johnson, director of the National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University. “That just helps drain water even faster,” she said.

Reutter said just two actions, both recommended by the state’s phosphorus task force nearly a decade ago, would help the lake a lot if all farms took them: Insert fertilizer into the ground and stop applying too much. The first involves pricey equipment. The second isn’t a major hurdle for farms using commercial fertilizer, but he said it’s “a real heavy lift for people putting on manure.” The analysis by Public Integrity and its partners shows only a small part of the problem because relatively few farms must send reports to the state or abide by limits, he said, and many are “applying way too much.”

Ohio’s inability to stem the flow of nutrients has costly consequences. To protect its residents from microcystins, cyanobacteria toxins that can sicken people, Toledo has spent $53 million on an under-construction ozone treatment system, $6.2 million for a powdered activated carbon system and $800,000 a year on the extra carbon and other agents that remove the toxin. The city also pays for a buoy system that measures water quality, which officials rely on to adapt their water treatment as algae conditions change.

And that’s just one place. The city of Oregon, which like Toledo taps Lake Erie for its drinking water, has had to spend extra, too. Across the country, more and more water systems are grappling with the costs of nutrient pollution.

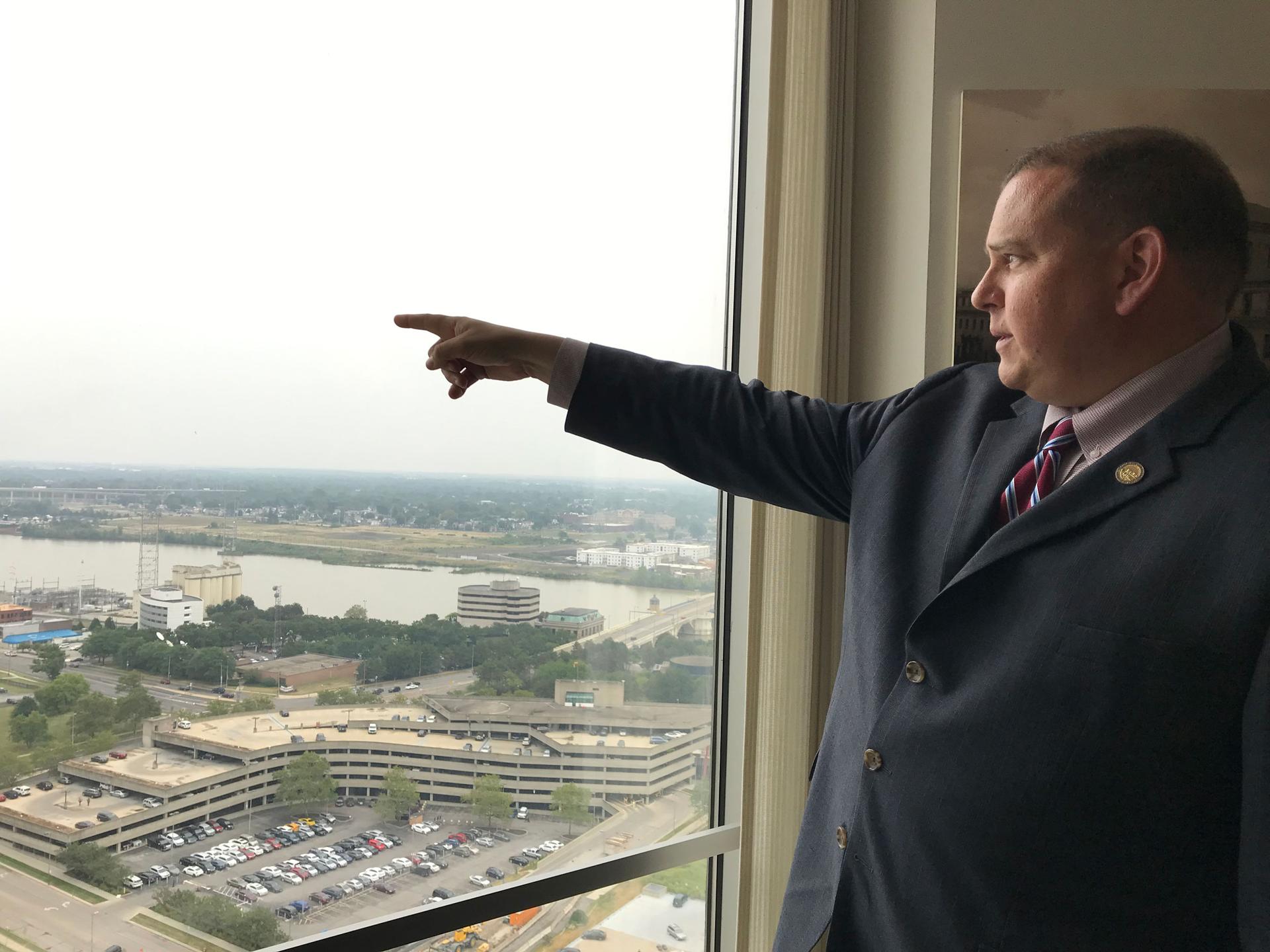

“We no longer have a drinking-water problem in this community,” Toledo’s mayor, Wade Kapszukiewicz, said in his office overlooking the Maumee River, which is full of farm runoff that dumps into the lake. “But that’s only true because of the incredible investment the taxpayers of Northwest Ohio have had to make.”

Toledo also spent $527 million over the last two decades to upgrade its sewage handling and reduce its own nutrient pollution. By Kapszukiewicz’s calculation, locals have paid twice over while the industry that’s sending most of the phosphorus to Lake Erie skates.

“It is a profound injustice that the citizens of Toledo have had to clean up a mess that other people have made,” he said.

Other ripple effects range from a sharp drop in business for western Lake Erie charter boat captains during key summer months to no-swimming warnings, which in 2019 stretched from the end of July through late August at a Lake Erie public beach near Toledo.

Lake Erie waterkeeper Sandy Bihn, whose small organization advocates for the lake, said her family largely stopped swimming in it at the end of the 1990s as algae mounted. Even boating is a problem: The stuff keeps clogging their engine. She praises the state of Ohio for its monitoring and other efforts to keep people safe from the toxins; many other places are playing catch up. But she thinks Ohio is doing an awful job reducing the pollution.

“The system is politicized to the point where they just don’t want to find the sources,” Bihn said.

‘Wherever you are, it’s coming’

Pam Taylor was in the driver’s seat, her former student Brittney Dulbs in the back, as they drove past a water source for Dulbs’ community last August.

“That’s Lake Adrian,” said Taylor, a retired high school teacher who farmed on the side and now volunteers as a concentrated animal feeding operation and water-quality watchdog. “Looks kind of green right now, Brittney.”

“Yeah,” Dulbs murmured.

They both live across the state line in Michigan, but their region’s farms and large animal operations eventually drain into Lake Erie. The algae drinking-water crisis that might have seemed somewhat distant when Toledo was battling it in 2014 hit home a few years later as Dulbs and others in her small city of Adrian complained that their own drinking water tasted earthy and smelled foul.

With Taylor’s help, Dulbs collected samples that tested positive for cyanobacteria, though not its toxins, which can come and go during a bloom.

Now Dulbs was on a field trip Taylor has taken many times before: a manure tour. Taylor paused at a creek she’d tested a few weeks earlier; the lab results, she said, came back with hits for microcystin, along with a separate cyanobacteria toxin and the bacteria E. coli, often found in animal manure and human feces.

Then she continued driving upstream, slowing as she passed one dairy operation after another that produce large amounts of manure, pointing out fallow fields with recent applications. She praised good management practices as she saw them. Those were few and far between.

Nutrient pollution sneaks up on you, Taylor warned. Once you realize you have a problem, it’s hard to undo and — for those whose drinking water relies on polluted sources — stressful to manage. There are no federal requirements for public water systems struggling with cyanobacteria, only EPA guidelines. The agency said it is gathering data to decide whether to regulate the contaminants; a rulemaking effort, if begun, could take years.

“The EPA needs to set some standards,” Taylor said. “You can kind of watch [cyanobacteria] spread all over the United States. It’s coming. Wherever you are, it’s coming to you.”

Earlier that week, Silvia Newell with Wright State University in Dayton took a class of students onto Lake Erie. Newell, whose specialty is aquatic biogeochemistry, researches nitrogen — another nutrient in commercial fertilizer and manure — and its role in harmful algae blooms. It’s a major player in the Gulf of Mexico dead zone. Newell and other scientists are showing that nitrogen helps phosphorus feed freshwater blooms like those in Lake Erie, too.

The early morning light painted the sky a peach-yellow as her class boarded a trawler and cast off from Put-in-Bay, an island vacation spot about 30 miles east of Toledo. Newell, lying on her stomach, head over the edge of the stern, helped the students pull up samples from below the surface. The water looked clean and inviting. No hint of sickly green scum.

But the lake was choppy, its waves potentially pushing cyanobacteria out of sight. They’re wily, too: They can float — or they can disappear down the water column in search of just the right amount of light and food.

Later that day in a lab overlooking the lake, Newell’s students put a few drops of the water they collected on a microscope slide. The blobby microorganisms there were a telltale bright green. A graduate student using a spectrofluorometer to analyze pigments in another sample found highly concentrated levels of cyanobacteria.

They were in that part of the lake after all, hidden from view.

This story is a collaboration between The World and the Center for Public Integrity — a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom that investigates betrayals of public trust — as well as Grist, a nonprofit media organization covering climate, justice, and sustainability for a national audience.

You can sign up for the Center for Public Integrity’s newsletter here and Grist’s newsletter here.