For years, mainstream environmental movements around the globe have excluded people of color.

Environmental sociologist Dorceta Taylor remembers being the only Black person in her environmental science class at Northeastern Illinois University in the early 1980s. When she asked her white professor why there weren’t more Black students, he quickly told her that it was “because Blacks are not interested in the environment,” she said.

This assumption ran counter to everything she knew. She had grown up in Jamaica, where people from all backgrounds were passionate about the environment and loved nature.

“We gardened, we hiked the mountains, we did all of those things,” she said.

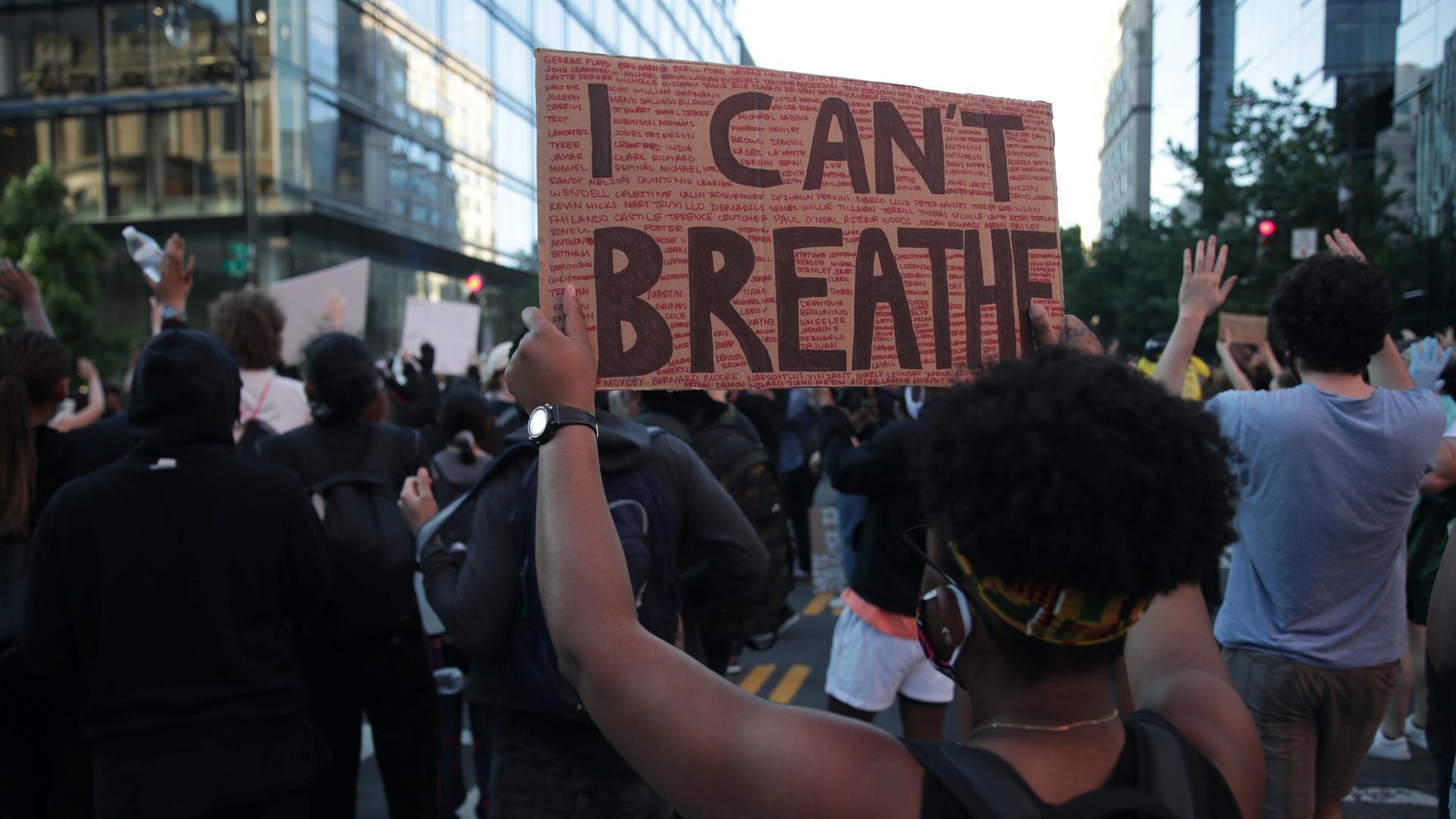

Today’s global Black Lives Matter protests have amplified calls for institutions of all kinds — including environmental groups — to challenge and dismantle centuries of systemic racism that have excluded people of color.

Related: Why many in public health support anti-racism protests

Taylor, until recently a professor of environmental racism at the University of Michigan, found that underrepresentation exists at environmental organizations across the United States. In 2014, just under 16% of people of color were represented in a survey of hundreds of organizations, compared to about 35% of the population, she said. In the early 1990s, only about 2% of the staff of environmental nongovernmental organizations were people of color.

In the UK, the environmental sector is one of the least diverse sectors of the economy.

Yet, people of color are disproportionately impacted by environmental degradation and climate change, and environmental organizations are being called to focus more than ever before on environmental justice.

In the past few weeks, big international green groups including Greenpeace and 350.org have responded with statements, videos and op-eds supporting Black Lives Matter and calling for racial justice.

Related: Black Lives Matter UK says climate change is racist

But environmental activist Suzanne Dhaliwal is skeptical this will translate into real inclusion, particularly in the UK, where she lives and works. Dhaliwal, who identifies as British Indian Canadian Sikh, grew up partly in Canada and spent much of her 20s working alongside big environmental nonprofits in the UK.

“We’re in a very difficult moment where it looks diverse, you know, our pictures are used. … But in terms of access to resources and having a say on the strategies that are used, and the support that we experience, I think it’s an all-time low.”

“We’re in a very difficult moment where it looks diverse, you know, our pictures are used,” she said. “But in terms of access to resources and having a say on the strategies that are used, and the support that we experience, I think it’s an all-time low.”

She says she grew frustrated when she couldn’t generate interest at her organizations to partner with Indigenous communities and focus on how environmental issues intersect with colonial legacies.

Related: Police beating of Indigenous chief fuels Canadian anti-racism protests

So, Dhaliwal started her own environmental nonprofit, UK Tar Sands Network, which works alongside Indigenous communities and organizations to campaign against UK companies investing in oil extraction in Alberta, Canada.

“Now, what I call for is direct funding of Black and Brown and Indigenous organizations and leadership training,” said Dhaliwal. “We need research money so that we can research new strategies.”

Other environmentalists are trying to change environmental organizations from within.

Samia Dumbuya just started a job with the European branch of international nonprofit Friends of the Earth, working on climate justice and energy issues. She lives in the UK.

As a Black person whose parents are refugees from Sierre Leone, talking about racial justice issues within the environmental movement is personal for her. She says she sees how climate change is affecting her parents’ home country with increasingly bad flooding and landslides.

“I like to talk to people about the role of colonialism and how the West exploits the lands of Asia, Africa, Latin America and specific islands where they basically degraded the environments and those lands — and it left people with nothing.”

“I like to talk to people about the role of colonialism and how the West exploits the lands of Asia, Africa, Latin America and specific islands where they basically degraded the environments and those lands — and it left people with nothing,” Dumbuya said. “And now, the West is saying we all need to be more environmentally conscious. And they look down on the ‘Global South,’ which is very hypocritical.”

Dumbuya thinks big environmental organizations can work together with smaller, newer groups as well as with the global Black Lives Matter movement, about how to use social media better to connect with younger, more diverse supporters.

“We don’t have to stick to these old traditional methods of activism — like, things are changing,” she said.

Valuing and nurturing people of color within the mainstream environmental movement has always been an issue, says Joe Curnow, professor at the University of Manitoba in Canada who researches social movements.

“I have seen a lot of BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and People of Color] folks feel like there’s not space for them in these mainstream organizations.”

“I have seen a lot of BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and People of Color] folks feel like there’s not space for them in these mainstream organizations,” she said. “There are a lot of the tensions there and who is getting recognized and who is getting celebrated as being a leader.”

Curnow said while it’s true that the hard work of anti-racist activists is having a positive effect on environmentalism by amplifying links between environmental degradation, colonialism and racism, pushing those ideas forward can take its toll.

“It can cost a lot for those people who choose to do it, emotionally and professionally,” Curnow said.

Related: How US protests highlight ‘anti-black racism across the globe’

It’s been almost 40 years since Taylor’s professor told her that Black people didn’t care about the environment.

As she watches the protests for racial equity across the world, she sees young people changing the environmental movement — pushing forward ideas that draw connections between race and the environment.

“They’re connecting the dots: Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and all these names, they immediately connect them with environmental justice, with climate, with health,” said Taylor. “Because they see it going toward the same neighborhood. Older people are still saying, ‘what does race have to do with the environment? I don’t see how it’s connected.’ Young people see it.”

“They’re connecting the dots: Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and all these names, they immediately connect them with environmental justice, with climate, with health,” Taylor said. “Because they see it going toward the same neighborhood. Older people are still saying, ‘What does race have to do with the environment? I don’t see how it’s connected.’ Young people see it.”

Across the globe, the urban spaces that are overpoliced and lack public investment also have the worst air quality and contaminated drinking water. The environmental movement will grow stronger with more diverse representation, but also by making these connections, Taylor said.

“Environmentalists all over the country are really taking note that they need to think of the environment now as not just the trees and the birds and the flowers, but the human relationships that are in them — and how these are really threatening some people way more than they’re threatening others.”