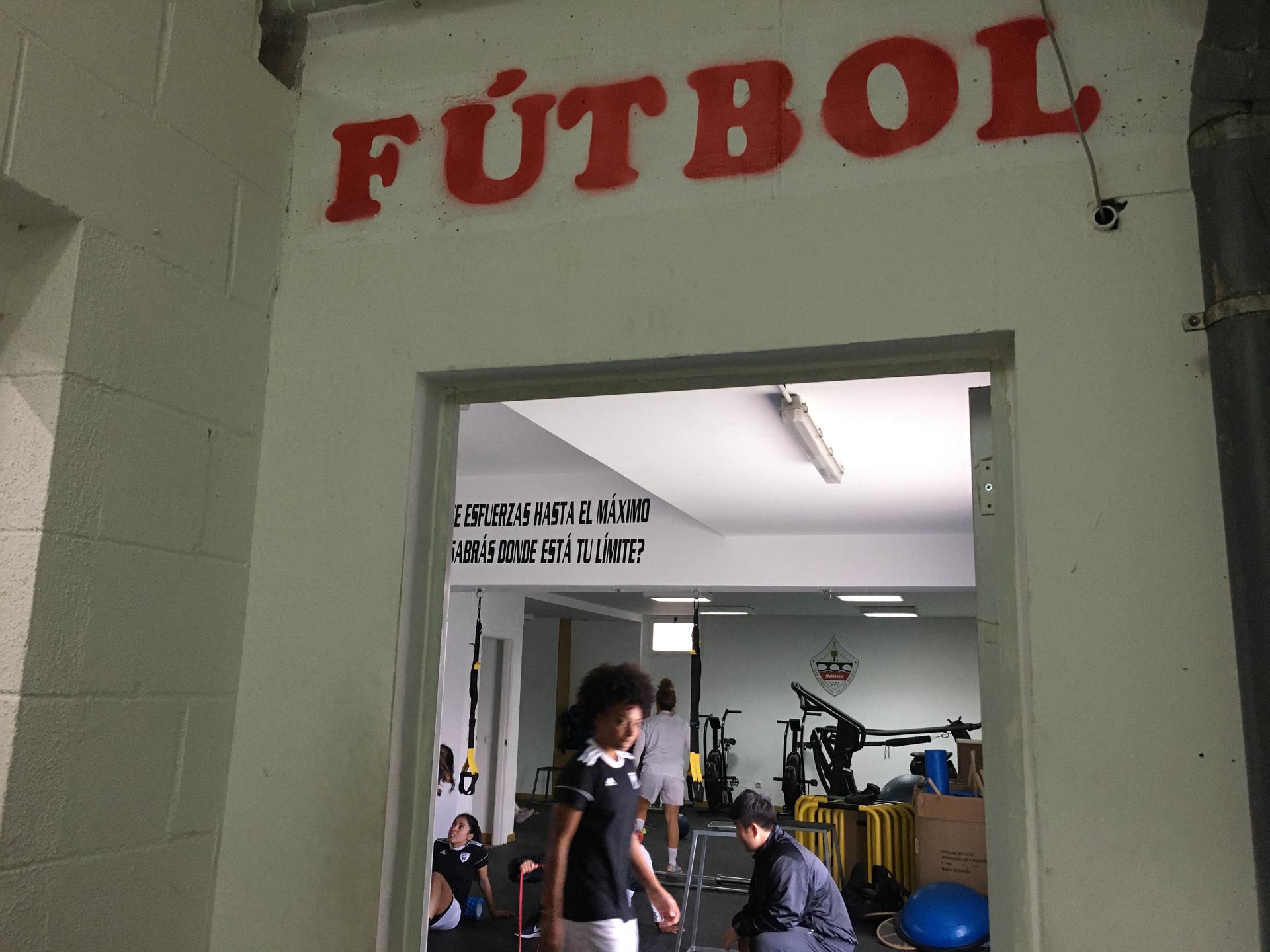

Members of Madrid Women’s Club go for a run on the soccer field, Madrid, Spain.

Spanish soccer will resume on June 11, after nearly three months without games. La Liga, Spain’s professional soccer league for men, was suspended in mid-March when the Spanish government put the country on lockdown in an attempt to contain the coronavirus pandemic. Now, the league championship matches will go until July 19, and games will be played with no crowds and with strict safety protocols.

The women’s league — which had its own championship — will not return. Their season was completely canceled in May, and the FC Barcelona female club was declared this year’s champions, since they were in the lead when the games were suspended.

Related: Women’s pro soccer made gains toward parity. Will coronavirus undo it?

But before the pandemic put the country on pause, women’s soccer in Spain had been making strides toward greater equity.

On Feb. 18, all 16 first-division teams signed a collective bargaining agreement that guaranteed female players a minimum wage, protocols for sexual abuse cases and paid maternity leave. It was a big step — and currently the only existing agreement of its kind for any women’s sport in Spain.

Forward Ana Lucía Martínez, from Madrid Women’s Club (or Madrid CFF), said this was a historic moment for Spain’s female soccer leagues. The World spoke to her in February — just one week after the agreement was signed, and just two weeks before her trainings were put on hold due to the pandemic.

Related: Under lockdown in Spain, hotels transform into field hospitals

“People in Spain are increasingly interested in women’s soccer,” she said, pointing to last year’s Women’s World Cup when a record 2 million people watched Spain’s national team lose to the United States 2-1.

But it’s still difficult for women to make a living from soccer, said the 30-year-old player. Since moving to Spain from Guatemala five years ago, Martínez has played for various first-division teams — the first club didn’t even give her a contract.

“It’s not like the men who retire and make millions. We have to worry about our future, get an education.”

“I was making 200 euros [$230] a month, which isn’t enough to live off of here,” she said. “I spent those days indoors, I never went out. I considered quitting because I couldn’t go on like that.”

Now, she’s one of the better-paid players in Madrid CFF — she makes enough money to pay her bills and concentrate on soccer full-time. But she says many of her teammates still rely on side jobs to get by.

“It’s not like the men who retire and make millions,” said Martínez. “We have to worry about our future, get an education.”

With the collective bargaining agreement signed, a career in soccer is beginning to look like a viable option for many women. But it took a year of negotiating and a week-long strike to get there.

Lawyer María José López represented the main soccer union involved in the negotiations.

“It was necessary to have this agreement for the sake of equality,” she said. “I mean, we’re in the 21st century.”

López says the agreement is exactly the same as the one signed by the men’s first-division teams decades ago, except for one thing: their salaries. In Spain, the base salary for men’s professional soccer is $170,000 a year; the women’s is $18,000.

Men’s games draw bigger crowds and more advertising dollars on Spanish TV — this means more revenue, which then translates into high salaries. López gets this. Still, she says the wage gap needs to shrink.

“The argument we always hear is: ‘These girls don’t bring in money, so they can’t make demands.’ No, no. These are working women who deserve worker’s rights.”

“The argument we always hear is: ‘These girls don’t bring in money, so they can’t make demands,’” said López. “No, no. These are working women who deserve worker’s rights.”

López says if advertisers would invest more in women’s games, there would be more interest — leading to more ticket sales, television programming and, eventually, higher salaries.

But all of this is on hold because of the pandemic.

Related: Two Berlin soccer teams now kept apart by COVID-19

Tamara Ramos directs another soccer union that signed the collective bargaining agreement this February. She says she expects the coronavirus outbreak to disproportionately affect the female leagues, which were already struggling with funding.

“Why do the men’s leagues come back after lockdown, but not the women’s? … Signing the collective bargaining agreement was a bittersweet moment. Of course, it was a big step forward. But we still have a long way to go.”

“Why do the men’s leagues come back after lockdown, but not the women’s?” she asks. “It’s all part of the same problem: lack of resources.”

In this case, that means coronavirus test kits and equipment to implement necessary safety measures.

“Signing the collective bargaining agreement was a bittersweet moment,” said Ramos. “Of course, it was a big step forward. But we still have a long way to go.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?