South Korea just repatriated two North Korean fishermen. Why?

A North Korean soldier keeps watch toward the South through a binocular telescope at the truce village of Panmunjom inside the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Koreas, South Korea, May 1, 2019.

Earlier this month, two North Korean fishermen sailed into South Korean waters — a situation that might normally grant them asylum from their oppressive regime.

But after the South Korean navy got hold of the North Korean squid boat on Nov. 2, Seoul didn’t exactly follow the usual protocol: Instead, they repatriated the two men back to Pyongyang through Panmunjom — a part of the Demilitarized Zone — for the first time in South Korean history.

Related: South Korea’s Moon calls for peace with North Korea

That’s because the two North Korean fishermen who were found, both in their 20s, are suspected of murdering 16 of their fellow crew members and allegedly dumping their bodies overboard (the bodies still haven’t been recovered). If true, it’s no doubt a gruesome crime. But if false, it would be a dire mistake — and now, North Korean defectors and human rights activists are blasting the South Korean government for sending the men back to “certain death” without a proper trial.

“This incident was not a slight violation of human rights, but an extreme violation. … North Korean defectors are very concerned. If the South Korean government recognizes them as criminals without any trial or investigation, then I am also a criminal as well.”

“This incident was not a slight violation of human rights, but an extreme violation,” said Jung Gwang-il, a Seoul-based North Korean defector and activist who heads an information dissemination organization called No Chain for North Korea. Through a translator, he said, “North Korean defectors are very concerned. If the South Korean government recognizes them as criminals without any trial or investigation, then I am also a criminal, as well.”

Related: Trump-Kim summit gave ‘master manipulator’ a global platform, says defector

Jung is an activist who sends packages of rice and USBs filled with illegal foreign media to everyday North Koreans by dumping them into the sea.

Read more: This group uses the tide to send bottles of rice and contraband to North Korea

But because of his work, he has gotten his fair share of unjust accusations, he said — including a statement from North Korean state media accusing him of human trafficking.

“These fishermen will certainly get the death penalty, and it’s sad because they are so young,” Jung said. “The way I see it, the South Korean government sent the North Korean defectors back as a gift to Kim Jong-un to get on his good side. They should not do that with people’s lives.”

‘No due process’

Seoul and Pyongyang have no clear extradition agreement, but South Korea’s decision to send the two fishermen back to the North calls into question what future protocol will be for accused criminals.

“Right now, the defectors are pissed and scared. This case is the matchstick that’s lighting the flame. … They are afraid that future defectors or they themselves might be targets if they are accused of crimes in North Korea before they defected. I personally don’t think that would happen, but from their perspective, there’s, unfortunately, genuine fear and concern that this could happen.”

“Right now, the defectors are pissed and scared. This case is the matchstick that’s lighting the flame,” said Henry Song, a North Korean human rights activist based in Washington, DC, who works with defectors. “They are afraid that future defectors or they themselves might be targets if they are accused of crimes in North Korea before they defected. I personally don’t think that would happen, but from their perspective, there’s, unfortunately, genuine fear and concern that this could happen.”

South Korea’s Ministry of Unification released a statement saying “there was no doubt” the two fishermen “had committed criminal acts” because they both gave consistent stories at separate interrogations. According to the ministry, the fishermen confessed to murdering their captain as retaliation for physical abuse. Then, they killed the remaining crew members on board.

The ministry also alleges that the fishermen dumped the murder weapons and bodies into the sea before attempting to clean the boat.

Nevertheless, some believe South Korea’s investigation simply wasn’t enough. On Nov. 12, Human Rights Watch published a statement condemning the repatriation, calling it “illegal under international law” and adding that “South Korean authorities should have thoroughly investigated the allegations.”

“There are so many unknowns: Did these men really kill their boatmates? Where’s the evidence?”

“There are so many unknowns: Did these men really kill their boatmates? Where’s the evidence? We don’t even know what happened,” Song said. “They should not have been repatriated and sent back, but they should have been put on trial in South Korea and even end up in South Korean jail. There was no due process here.”

Directing diplomacy

It took South Korea’s navy two days to chase and capture the North Korean fishermen after spotting them, but it’s unclear how closely Pyongyang and Seoul were communicating before the decision to repatriate. South Korean authorities did discuss the matter with North Korea, and ultimately made a decision to send them back to the North within 48 hours of seizing the vessel.

“I think the process should have at least been longer, but I think it was the right decision for the government.”

“I think the process should have at least been longer, but I think it was the right decision for the government,” said C. Harrison Kim, a professor at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, and author of “Heroes and Toilers: Work as Life in Postwar North Korea, 1953-1961.” “As South Korea and North Korea try to become more normalized neighbors, I think it’s important that South Korea recognizes North Korea as a legitimate entity, in which case extradition needs to be respected.”

The North Korean fishermen are legally entitled to request asylum, Kim said, but there’s no certainty that the South Korean government would grant it — especially since they’re accused of such heinous crimes. Yet, human rights activists say that the hasty repatriation shows how little the South Korean government considers the lives of North Korean runaways who face hunger, extreme political censorship and widespread human rights abuses in their home country.

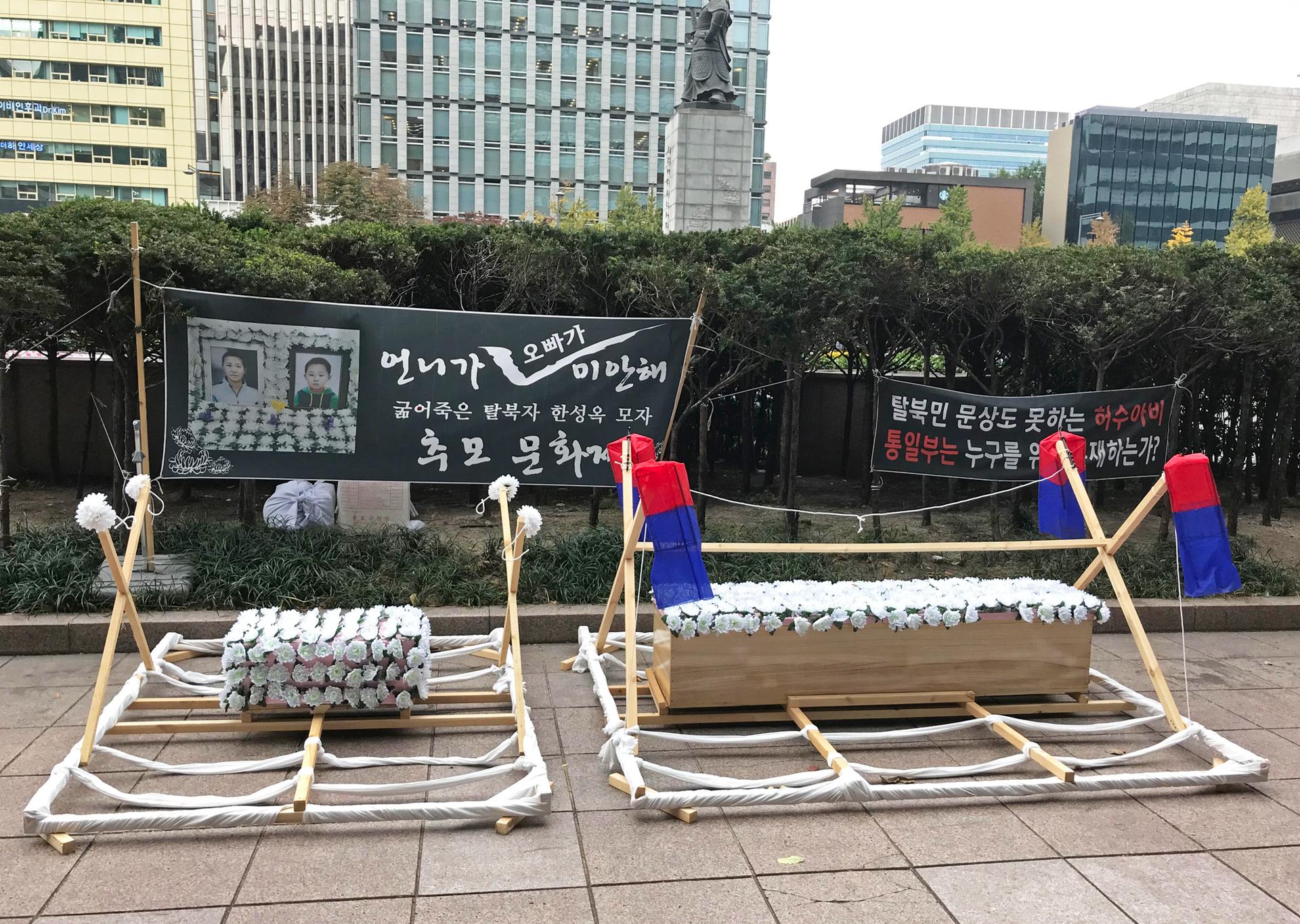

“[Defectors]are calling President Moon [Jae-in] an utter hypocrite. He’s known as a human rights lawyer and his motto is ‘putting people first,’ but this is really about Kim Jong-un being put first,” Song said. He added that the South Korean government paid little attention to another recent, high-profile incident: In September, a North Korean refugee mother and her 6-year-old son were found dead in their Seoul-area apartment. Police suspect that they died of starvation.

“South Korean officials didn’t really show any concern, and I don’t think any of them showed up to the makeshift memorial for them in downtown Seoul. The defector community is very angry,” Song said.

“They came from North Korea because they were starving and they died in South Korea from starvation,” Jung added. “It’s ridiculous.”

However, President Moon no doubt faces a difficult challenge in trying to make diplomatic progress: Harping on North Korean human rights runs the risk of prematurely ending both South Korea and the United States’ newfound relations with Pyongyang. On Nov. 14, South Korea withdrew from a list of more than 40 co-sponsors on a 2008 UN General Assembly resolution to denounce North Korean human rights abuses.

“I think Moon Jae-in is highly supportive of the philosophy that a better diplomatic relationship has to come first before the human rights issue can be addressed,” C. Harrison Kim said. “Moon Jae-in sees human rights as a political issue first and foremost.”

For now, defectors and activists say they’re not giving up.

“This is not going to go down quietly. The defectors are going to keep pressing on this issue,” Song said. “[The South Korean government] should brace for more discontent from us activists. We are not going to let up on this.”