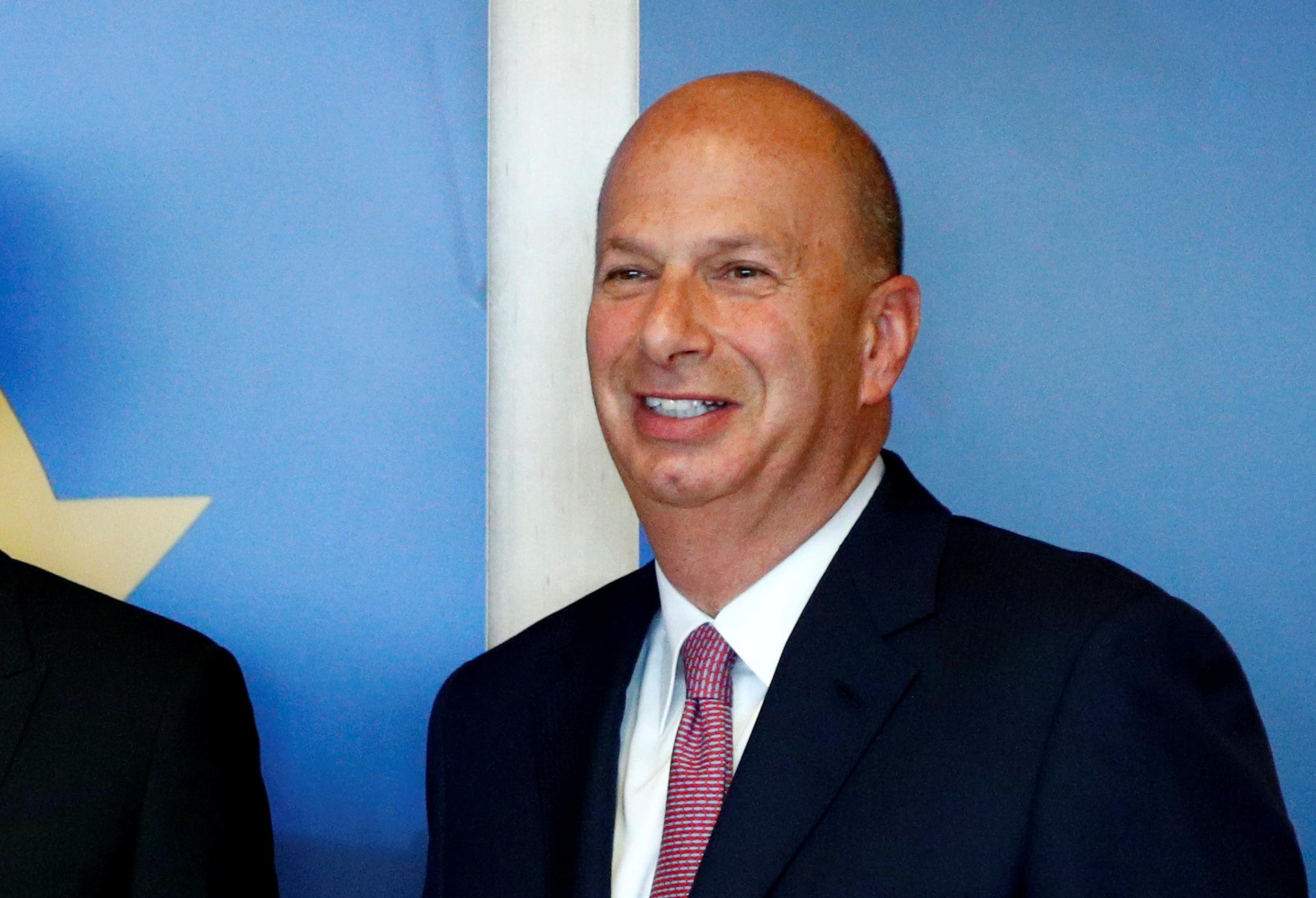

How rich people like Gordon Sondland buy their way to being US ambassadors – 5 questions answered

Some positions attract more political appointments — like those in Western Europe.

In every other developed democratic country, the role of ambassador, with only very rare exceptions, is given to career diplomats who have spent decades learning the art of international relations.

In the US, however, many ambassadors are untrained in diplomacy and have simply bought their way into a prestigious post.

Related: Ambassador Huntsman: US-Russia estrangement ‘has gone on too long’

The involvement of the American ambassador to the European Union, Gordon Sondland, in the Ukraine scandal has prompted interest in the media and Congress in the role of non-career ambassadors like him.

On Oct. 30, US Rep. Ami Bera, a Democrat from California, introduced legislation that would require at least 70% of a president’s ambassadorial appointments to come from the ranks of career Foreign Service officers and civil servants.

Career appointees have to spend decades working their way up through the ranks in government before being nominated, as I did before becoming an ambassador in Mozambique and later in Peru.

Related: Trump names former news anchor as new UN ambassador

Bera’s bill likely does not have the support in Congress to ever be enacted. More importantly, it does not address what I think is the real problem with political appointee ambassadors. That is the selling of the title in exchange for campaign contributions to people who are clearly unqualified for the job.

While this is a time-honored practice used by presidents of both parties, it has arguably gotten worse under the Trump administration.

1. Who picks ambassadors?

The Constitution says nothing about the qualifications required to be an ambassador. All it says is the president can appoint them with the advice and consent of the Senate.

In other words, a president can appoint whoever he wants for whatever reason he wants.

The Senate can refuse to confirm a nominee, but that has not happened in over a century. Instead, occasionally the Senate will refuse to vote on the nomination and the nominee languishes until either the Senate does decide to act or the White House withdraws the nomination.

That kind of delay is not uncommon, but it is almost always due to policy disputes between the two branches, rather than anything to do with the qualifications of the person being proposed for an ambassadorship.

Related: Yovanovitch testimony shows US foreign policy is ‘in shambles,’ former diplomat says

2. Who’s qualified?

Deciding what qualifies someone to be the personal representative of the president abroad is therefore almost entirely up to the president.

During the Nixon administration, the president’s personal lawyer asked the wife of a wealthy department store owner for a $250,000 campaign contribution in exchange for the ambassadorship to Costa Rica. She famously replied, “That’s a lot to pay for Costa Rica, isn’t it?” She eventually went to Luxembourg as an ambassador and shortly thereafter wrote checks to the Nixon reelection campaign that added up to $300,000.

That overt quid pro quo prompted the passage of the Foreign Service Act of 1980.

The act states that those appointed to be an ambassador “should possess clearly demonstrated competence to perform the duties of a chief of mission,” including knowledge of the language, history and culture of the country.

It added that, given those requirements, such positions “should normally be accorded to career members of the Foreign Service, though circumstance will warrant appointments from time to time of qualified individuals who are not.”

It also stressed that “contributions to political campaigns should not be a factor in the appointment of an individual as a chief of mission.”

3. How many ambassadors are career diplomats?

Despite its intended purpose, the act did little to change how business was done in Washington.

The percentage of political appointee ambassadors only went down very slightly, hovering around 30% after the act was passed.

The one exception was the Reagan administration, which got the figure up to 38% by sending Reaganites to places like Rwanda and Malawi, where normally only career ambassadors would dare to tread.

The question of percentages of political versus career ambassadors is one that sometimes attracts media interest, mainly because it is always higher than the usual 30% in the early part of any presidential term. That percentage cannot really be calculated in a meaningful way until the end of a term, because most political appointments are made in its first years.

For example, the percentage of political appointee ambassadors under Trump currently stands at about 45%. However, Trump has left 10 posts vacant that have always been filled by career ambassadors.

Another seven posts that would be career slots are in countries where relations have been downgraded or suspended, such as Venezuela and Bolivia. Most of those embassies will likely be filled by career people at some point.

In terms of posts that are normally held by career diplomats, there are only six — Croatia, Chile, Poland, Thailand, United Arab Emirates and Fiji — that currently have political appointee ambassadors.

4. How much does an ambassadorship cost?

While some political appointees are political allies and friends of the president, for many postings — particularly in Western Europe and the Caribbean, where 80% of the ambassadors are political appointees — who gets the job depends on money.

Even after the Foreign Service Act was passed, political contributions continued to play such a role that it was possible to estimate how much more London would cost than Lisbon. The larger a country’s economy and the number of tourists that visit it, the higher the price of becoming an ambassador.

And for those who want to add a fancy title to their resume and have the money, a six- or even seven-figure price is not too high.

For his first inauguration, President Obama put a limit of $50,000 on contributions. President George W. Bush capped his at $250,000.

For Trump, the sky was the limit and the floodgates were opened for those who wanted to buy access or influence. More than 250 donors gave $100,000 or more, which amounted to over 90% of the $107 million that was collected for the inaugural festivities.

Though Sondland had not backed Trump in his bid to be the Republican candidate, he contributed $1 million after the election to Trump’s inaugural committee.

Under Trump, it’s not just the posts in rich countries and tropical paradises that are for sale. United Nations ambassador Kelly Craft and her husband contributed over $2 million to Trump’s election campaign and inauguration. She also gave generously to over half the Republican senators on the Foreign Relations Committee that had to approve her nomination.

So while the percentage of political-appointee ambassadors may not increase all that much by the end of Trump’s current term, the price for buying one certainly has.

I think this practice of selling ambassadorships is unlikely to change, despite the image it creates abroad when a person with no knowledge of a country is put in charge of the American embassy there.

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren has said she will appoint no big donors as ambassadors — period. But when I have contacted the campaigns of every other person seeking the nomination to ask if they would make a similar pledge, I have been met with silence. That is because, in Washington, money does the talking.

Dennis Jett is a professor of international affairs at Pennsylvania State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.