Spain’s coal miners continue to wait for their country’s ‘Green New Deal’

The San Nicolas mine in Spain’s northern region of Asturias is the last working coal mine in all of Spain. At its peak, it employed around 2,000 people — today, about 200 people work there.

Spain’s government isn’t getting much done these days.

No political party won a majority in the nation’s general elections in April, and parliamentary negotiations to form a new government remain at a standstill. If a new government can’t be formed by Sept. 23, Spanish voters will go back to the polls in November for another general election, in what would be the country’s fourth in four years.

One of the many projects on hold is Spain’s “ecological transition” — a push to close all of the country’s coal mines and transition to renewable energies, like wind and solar.

Related: How a forest became Germany’s poster child for a coal exit

People in Spain’s northern region of Asturias are anxiously waiting to see how things play out. They’ve been mining there for 150 years. But today, the industry is almost dead.

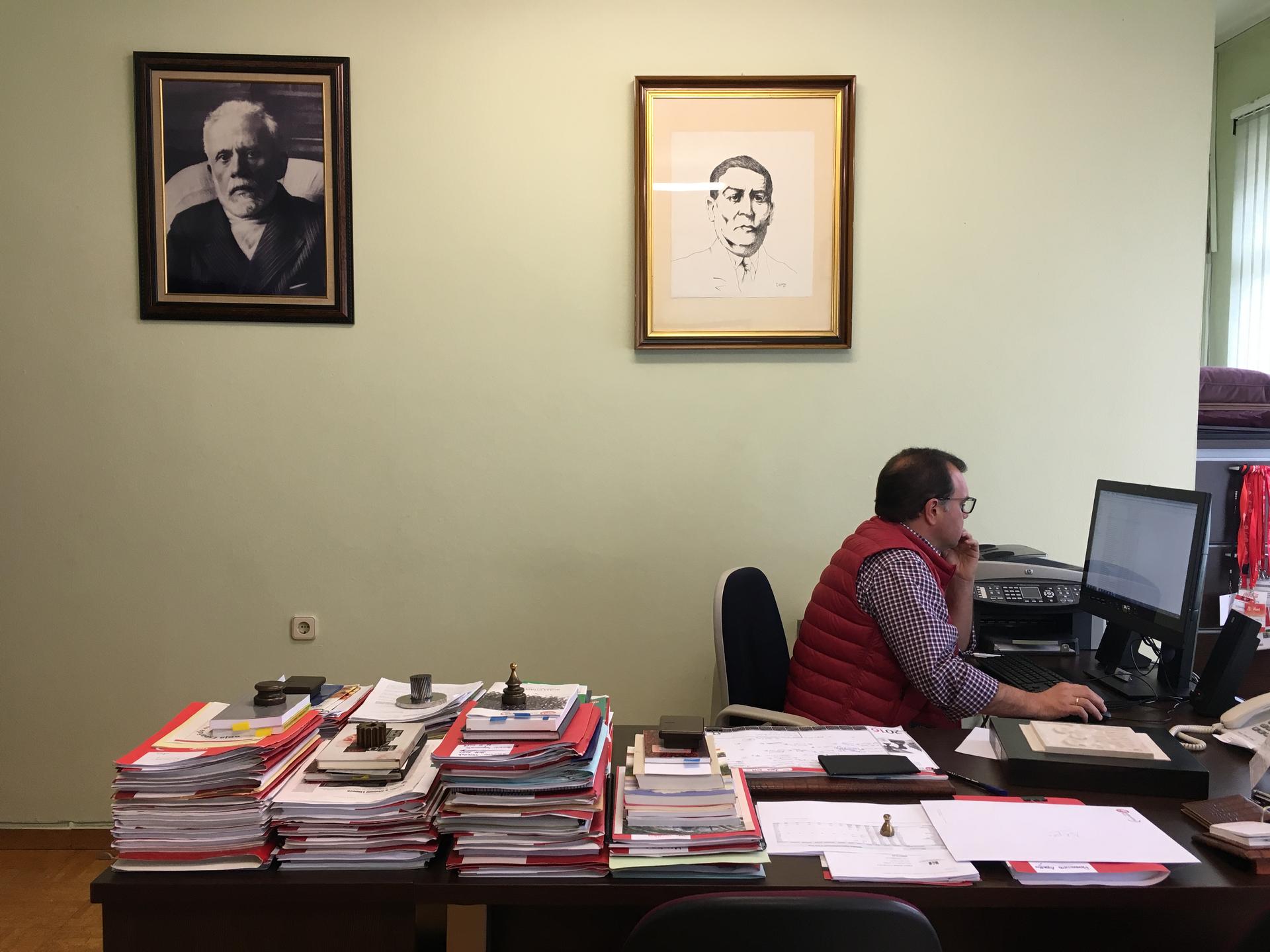

During a recent weekday at the San Nicolás coal mine, dozens of miners — mostly young men — walked out of their shift around 2 in the afternoon, in a hurry to get home and eat lunch. The underground mine is located in a valley, surrounded by lush, green hills. At its peak, the mine employed around 2,000 people — today, about 200 work there. It’s the last working coal mine in all of Spain.

Gorka Peña, 36, has been working at San Nicolás for nine years. He says his father was also a miner, and he didn’t expect to end up in the trade himself.

“There’s no future here, no youth,” Peña says. “The towns are becoming more depopulated, its residents are getting older. You don’t have anywhere to go, so you have to migrate.”

Last October, the leading mining union struck a deal with Spain’s Socialist government to funnel 220 million euros ($246 million) into the region over the next decade, which would include retraining programs and investment in new industries.

“In Asturias, what we’re asking for and what we need is for this ‘ecological transition’ to be exactly what it says it is,” says José Luis Alperi, the union’s spokesperson. “That is, that no one be left behind.”

Alperi is cautiously optimistic. The union has struck deals with the Spanish government in the past, with both liberal and conservative parties. But Alperi says the central government has broken its promises, and they haven’t invested enough in the region.

Retired miner Fredo Ouviña, on the other hand, is completely skeptical of the Spanish government, past and present. He sits at a café with three other friends, drinking afternoon beers in the mining town of San Martín. Ouviña says a lot of the money that was supposed to go towards investing in new industries in the region has been badly handled.

“The type of job opportunities [the Spanish government] wants to provide aren’t pragmatic, they’re not practical,” Ouviña says.

Related: Germany talks a good game on climate, but it’s still stuck on coal

There are no new green energy jobs, he adds, because there hasn’t been a transition away from fossil fuels — Spain continues to import coal from other countries where it’s much cheaper.

“It’s an economic and political issue,” Ouviña says. “Here, miners are paid a living wage with benefits, which brings the price of coal up.”

Environmental activist Fructuoso Pontigo agrees.

“All the mines in Asturias have closed, but we continue to import coal,” he says. “It’s kind of a contradiction, no?”

Pontigo says 80% of the coal burned in Asturia’s power plants is imported from foreign countries. The region is among Europe’s dirtiest, producing vast amounts of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change.

Many miners in Asturias say they’ve seen signs that things were moving forward under the Socialists — but again, their coalition government is stalled — and the miners are stuck waiting for a new government to form.

Related: Britain built an empire out of coal. Now it’s giving it up. Why can’t the US?

Back at the café, retired miners continue drinking beers and talking about their history of unionizing. Ángeles Rubio breaks into an old mining song about the region’s patron saint. She starts tearing up as she sings; it’s a song her father, a miner, used to whistle as he got ready for work.

“Life at the coal mine was difficult, but many people were able to live a good life here,” Rubio says.

The mines shaped the identity of the town, but Rubio points to the empty streets with barely any young people around, and says she sees the future of Asturias as dark as the color of coal.

The article you just read is free because dedicated readers and listeners like you chose to support our nonprofit newsroom. Our team works tirelessly to ensure you hear the latest in international, human-centered reporting every weekday. But our work would not be possible without you. We need your help.

Make a gift today to help us reach our $25,000 goal and keep The World going strong. Every gift will get us one step closer.