If Thwaites Glacier collapses, it would change global coastlines forever

Drone footage shows large icebergs that have recently broken off the ice shelf in West Antarctica.

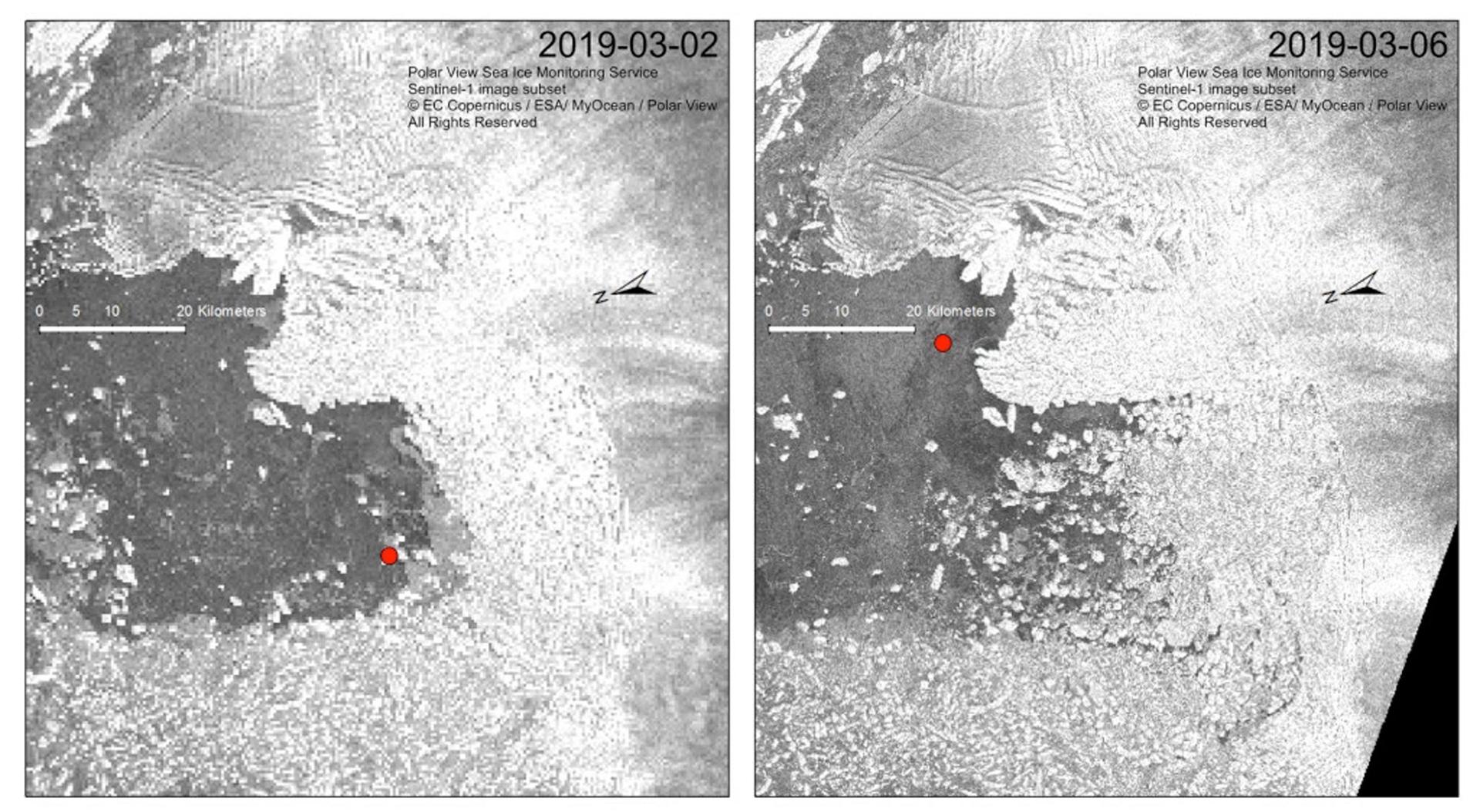

Days after the Nathaniel B. Palmer became the first ship to sail across the 75-mile face of West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier, a piece of its floating ice shelf bigger than Manhattan crumbled off the glacier into a flotilla of icebergs.

Scientists aboard noticed something had changed when the research vessel tried to navigate to a spot in front of the Florida-sized glacier and was blocked by ice-choked seas.

“What we didn’t realize at the time is the ice [front] was coming out to chase us out,” said Rob Larter, a marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and chief scientist on the ship. “The entire embayment where we’d been working for several days was littered with icebergs.”

Satellite images soon showed where these icebergs were coming from. A roughly 20-mile stretch of Thwaites had fractured into mile-long icebergs that were now being blown out into the bay in front of Thwaites.

“It was quite remarkable,” Larter said of the satellite images. “Suddenly, it was making sense with what we were seeing out of the windows.”

Thwaites Glacier is melting fast, and scientists fear its collapse could one day destabilize surrounding glaciers and eventually trigger up to 11 feet of global sea level rise.

This winter’s expedition aboard the Palmer marked the first field season of a five-year, international research collaboration to discover just how much, and how fast, Thwaites Glacier might add to rising seas.

The massive blowout of icebergs won’t itself change sea levels, as the ice that fractured off deep into the ice shelf had already been floating. But it is a sign of the glacier’s instability.

“It’s another step in the [progressive] retreat,” Larter said. Coupled with the thinning of the glacier and its faster flow, “this [event] is one expression of the fact that Thwaites Glacier is putting more and more ice into the ocean.”

Thwaites’ ice shelf stabilizes the whole glacier, acting like a cork in a wine bottle to slow the seaward flow of ice from the continent’s interior. This big blowout confirmed that there’s very little actual ice shelf left in the western part of Thwaites Glacier. Instead, much of the ice there is actually what scientists call a “mélange,” a slushy mix of icebergs and other floating bits of ice formed by fracturing at an ice front.

“You’d expect it might lead to even further acceleration of flow of the glacier,” Larter said of the blowout.

During the next summer thaw, scientists will watch to see if more of the ice shelf inland from the mélange starts to crumble.

“Whether it leads directly to further changes or not, we just have to wait and see,” Larter said. `

An inherently unstable glacier

If the entire floating ice shelf at Thwaites fractures into icebergs, what’s left at the edge of the glacier is a giant cliff of ice whose shape makes it particularly vulnerable to runaway collapse.

The seafloor underneath the glacier slopes downward as it goes inland in what scientists call a “retrograde slope,” and the ice sitting on top of it gets thicker and thicker. If Thwaites retreats far enough inland and reaches a certain thickness, physics dictates it will start collapsing under its own weight. And ice cliff modeling suggests that if that process starts, there might not be anything to stop it.

“You could get a domino effect of icebergs falling off of the edge of an ice sheet,” said Ali Graham, a marine geophysicist on the ship from the UK’s University of Exeter.

“There’s still a debate over what [this collapse] would look like,” Graham said. “We could be observing it right now and not really realize that it’s happening, and that’s pretty scary to think about.”

The ultimate goal of the five-year research collaboration is to collect data — on the glacier itself, the bedrock beneath it, and the warm water melting it — that will improve models and fill in some of the unknowns about what the glacier’s collapse might look like. And how fast it might happen once it starts.

“How quickly can you feasibly collapse something like Thwaites?” Graham said. “Is it over a century, over a thousand years, or can you do in a decade? I don’t think anyone can, hand on heart, say which of those it is yet. And that’s a concern.”

In a paper that outlined this marine ice cliff instability theory in 2016, authors Rob DeConto from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and David Pollard from Penn State University raised alarm by predicting that Antarctica by itself could contribute up to 3 feet of sea level rise by 2100.

New, not-yet-published research from the same pair revises the estimate for the end of the century downward substantially, but the longer-term picture is still bleak, with a rate of sea level rise that could “be very challenging for coastal planners and engineers to cope with,” DeConto wrote in an email, “likely leading to large-scale retreat from the coast in some places and loss of some low lying islands.”

Their 2016 research, which predicts how marine ice cliffs will react to atmospheric warming under a variety of future greenhouse gas scenarios, found that in a future where we quickly and radically cut greenhouse gas emissions, the West Antarctic ice sheet would be relatively stable for centuries. In a future where carbon emissions continue unabated, warming air temperatures would force its collapse within 250 years.

DeConto said they are still working to identify the exact tipping point that would trigger this dramatic fracturing of the West Antarctic ice sheet, but work he presented at the American Geophysical Union meeting this past winter suggests it’s somewhere between 2-3 degrees Celsius of warming. If every country met its Paris Agreement commitments, the world would warm to 2.7 degrees Celsius.

Planning for uncertainty

The questions swirling around the future of the West Antarctic ice sheet add to the considerable uncertainty policymakers and planners face when trying to prepare for sea level rise.

The United States’ National Climate Assessment estimates we’ll see 1-4 feet of sea level rise by 2100, citing the complicated dynamics of Greenland’s and Antarctica’s ice sheets as “the primary reason that projections of global sea level rise includes such a wide range of plausible future conditions.”

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects between roughly 1 1/2 to 3 feet of sea level rise under a “business as usual” carbon emissions scenario, or 1 to 2 feet if we start cutting carbon immediately and dramatically.

Each scenario includes only a small amount of melting from Antarctica.

This means that cities and countries using IPCC data to build their own localized sea level rise projections are likewise only planning for a small amount of loss from West Antarctica, which might prove to be an underestimation. Vietnam, for example, where more than a quarter of the population would face inundation if the entire West Antarctic ice sheet were to collapse, uses IPCC data in its national climate report.

But the IPCC, too, serves up its estimates with an important caveat, stating that “the collapse of the marine-based sectors of the Antarctic ice sheet, if initiated, could cause [global mean sea level] to rise substantially above the likely range during the 21st century.

Boston as a case study

Some communities are going beyond these national and international projections and incorporating potential melting from Antarctica’s ice sheets into their local sea level rise estimates.

The city of Boston is planning for more than 3 feet of sea level rise by 2070, and between 2 and 7 feet by 2100.

In the near term, these changes will mean more frequent, coastal flooding in low-lying areas, including some of Boston’s most historic neighborhoods. The city is working with communities to develop neighborhood plans focusing on solutions like raised parks along Boston Harbor that serve both as spaces for recreation and flood barriers.

But the wide range of scenarios possible by 2100 makes planning for century’s end impossible, according to Alisha Pegan, coordinator of the city’s Climate Ready Boston program.

“We’d like to plan for 2100. It’s just the science right now is so uncertain that it’s planning for a variance of 4 feet of sea level rise,” Pegan said. “When we have better data, better science, then we can make more informed decisions.”

None of the protections necessary to preserve coastal communities will come cheap. A recent study put the price tag of protecting the US from rising seas over the next two decades at more than $400 billion.

For some communities, 2 feet of sea level rise, which would come if Thwaites Glacier melts completely, represents an existential threat. For Boston, it’s something the city plans to adapt to.

“Our challenge is that [sea levels are] going to keep going up,” said Julie Wormser from the Boston-area Mystic River Watershed Association.

Eleven feet of sea level rise, which would come from the collapse of the entire West Antarctic ice sheet, is another story entirely.

Many low-lying coastal cities, from the US to the Netherlands to Bangladesh, are built on land partially reclaimed from the sea. In Boston, much of the current downtown didn’t exist prior to the arrival of European settlers.

“They filled in a lot of the [Boston] Harbor with horses and shovels,” Wormser said, “and they never contemplated sea level rise.”

Now, about a third of Boston is at risk of coastal flooding if sea levels rise between 2 and 8 feet higher than they are today, Wormser said. At 11 feet, much of the city would be underwater without massive, new infrastructure projects to protect it.

But even the city government isn’t sure that level of protection is possible.

“I don’t have an answer for that,” Pegan said when asked if it was even feasible to protect Boston from 11 feet of sea level rise. “There are a lot of people interested in making sure that we can do this, but I can’t say for sure right now.”

Boston, of course, is not alone, nor is it the most vulnerable. Pacific Island nations like Kiribati, the Marshall Islands and the Maldives would be wiped off the map if the West Antarctic ice sheet were to collapse entirely. One World Bank estimate suggests more than 90 million people in just 12 developing countries would be displaced. In the US, just half that amount of sea level rise could prompt a coastal exodus that would rival the great migration.

Scientists studying Thwaites Glacier hope to give policymakers a better sense of just how fast sea levels might rise in coming decades, and whether it’s still possible to halt the kind of massive sea level rise it could cause, or just slow its onset.

The question then is what we choose to do about it.