A Japanese American newspaper chronicles the ‘searing’ history of immigrant incarceration

(Left to right) Gwen Muranaka, Mikey Hirano Culross and Mario Reyes, in the newsroom of the last remaining Japanese American daily newspaper, The Rafu Shimpo in downtown Los Angeles, 2010.

Twice per week, Maggie Ishino, a 94-year-old newspaper columnist, takes three buses across Los Angeles’ sprawl to the office of The Rafu Shimpo, the last bilingual Japanese-English daily paper in the US mainland.

At her seat in the middle of a row of journalists, Ishino gets to work on her column, “Maggie’s Meow.” In it, she shares her frank observations: Hipster beards look like a “lion with an undeveloped mane.” Living alone makes you “the odd one out” at family gatherings.

Sometimes, she feels compelled to write about what she calls “camp.” But this is no summer camp. She means the horse stables and desolate swath of land in the Arizona desert where the US government forced her to live alongside thousands of other Japanese Americans during World War II. They were labeled enemy aliens and a threat to national security. Never mind that Ishino, then a teenager, was born in San Diego and had never been to Japan.

Related: Immigrant detention centers are a grim reminder of Japanese American history

Decades before the US government detained Central American children and families at the southern border, Ishino’s family was among the 120,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps during the war. Fewer than 20,000 are alive today, almost all of whom were children at the time, according to estimates from Densho, an organization dedicated to preserving memories of Japanese American incarceration.

Like Ishino, they are now approaching the end of their lives at a time when a new generation of children are being detained in the US, creating a special urgency for Japanese American institutions like The Rafu Shimpo to preserve their stories.

“The camp experience is this throughline for the entire community, and that will always be part of our narrative,” said Gwen Muranaka, The Rafu Shimpo’s editor, whose own parents were incarcerated. “That experience is so searing that there’s a sense that we need to be vigilant when these things happen again, and there’s a real yearning to let people know what’s happened and to give witness.”

In one column, Ishino recounted how she knew her life had changed completely when a soldier stuck a gun in her face. Her younger brother’s first bed was a horse’s trough.

“It seems so many people who are unaware of this tragedy need to know this dark period for the Japanese after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.”

“It seems so many people who are unaware of this tragedy need to know this dark period for the Japanese after the bombing of Pearl Harbor,” Ishino wrote.

The challenges of keeping young people healthy in cramped quarters — which the US government is confronting again today as it detains migrant children — was something Ishino experienced seven decades ago.

“There were many sleepless nights holding a crying infant and comforting a very ill and very unhappy sister when they contacted contagious diseases such as mumps, whooping cough, chicken pox,” Ishino wrote. “These so-called ‘childhood diseases’ really did spread to children because of the close quarters.”

A Japanese American institution

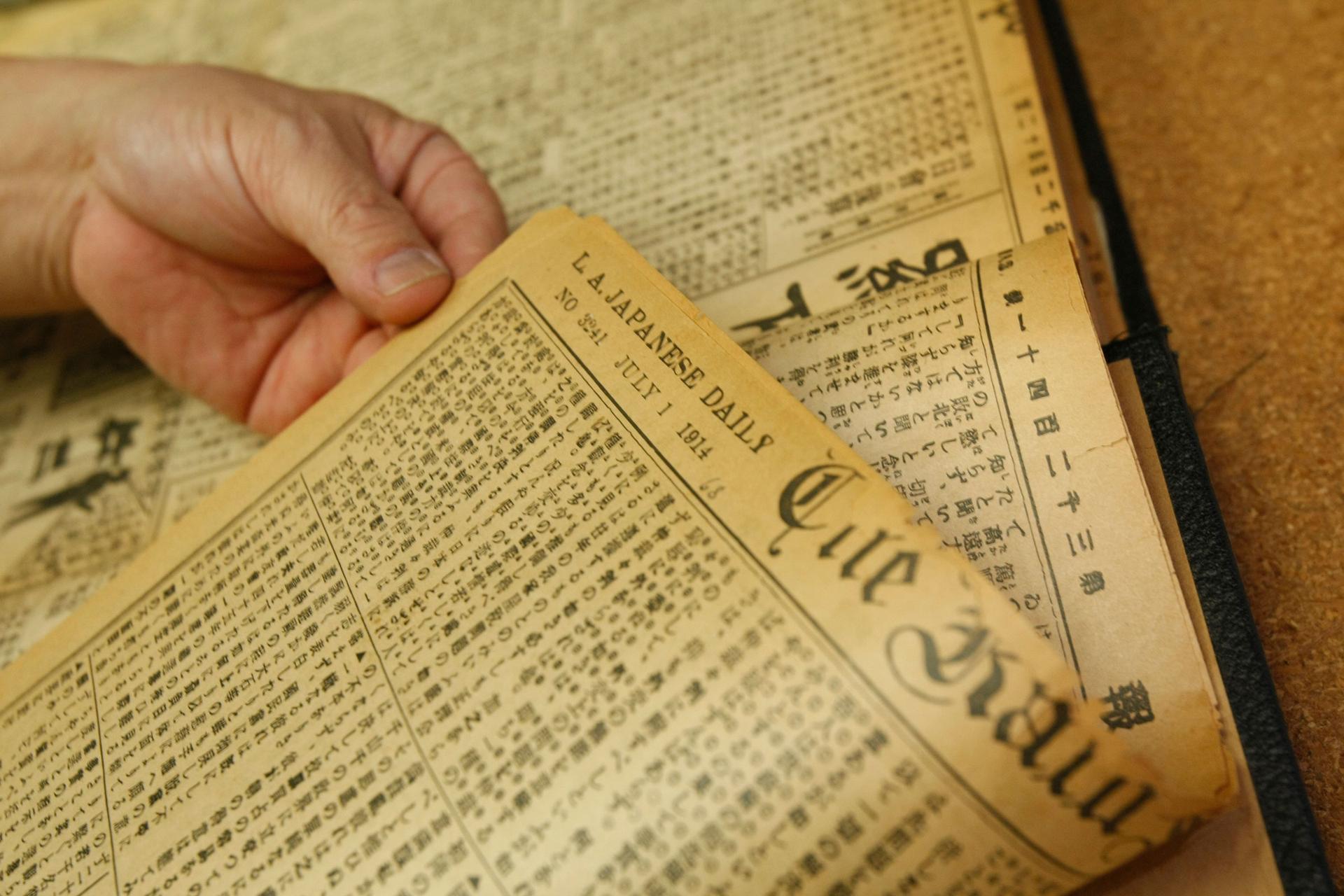

The Rafu Shimpo struggled to survive in the 1940s as community members and its own staff were incarcerated. Its newsroom vacant, the paper was forced to stop publishing for four years.

Within hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the FBI arrested the newspaper’s then-editor, H.T. Komai, the grandfather of the paper’s current publisher. For months, the government heavily censored the paper, until April 1942, when Southern California residents of Japanese descent, including Ishino’s family, were forcibly moved to camps. The last headline read, “Before long we will be your ‘Rafu Shimpo’ again.”

The publisher “hid the rotary press, Japanese printing type, and other equipment under his building floorboards with an intention that he would come back to Los Angeles to resume the newspaper operation,” Eiichiro Azuma, an associate professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, writes in Densho’s encyclopedia of the Japanese American incarceration experience. And indeed, after the war, in 1946, The Rafu Shimpo was the first Japanese-English publication in the US to resume publishing.

Today, the paper is still in the hands of the same family that once hid the press and printing type. But they face pressures that plague the entire industry: declining readership and advertising revenue. High levels of intermarriage and dwindling Japanese immigration have also reduced readership. The paper was almost forced to shut down in 2016, but managed to increase subscriptions.

Its purpose is changing, too. Where it used to tell stories of a community rebuilding itself after the war, the paper now memorializes that generation’s passing and adapts the lessons from incarceration elsewhere.

“Our role has been to chronicle what they’ve done. To help people understand what’s happening,” Muranaka said. “And at this moment, it’s to mark their passing.”

Linking the past to the present

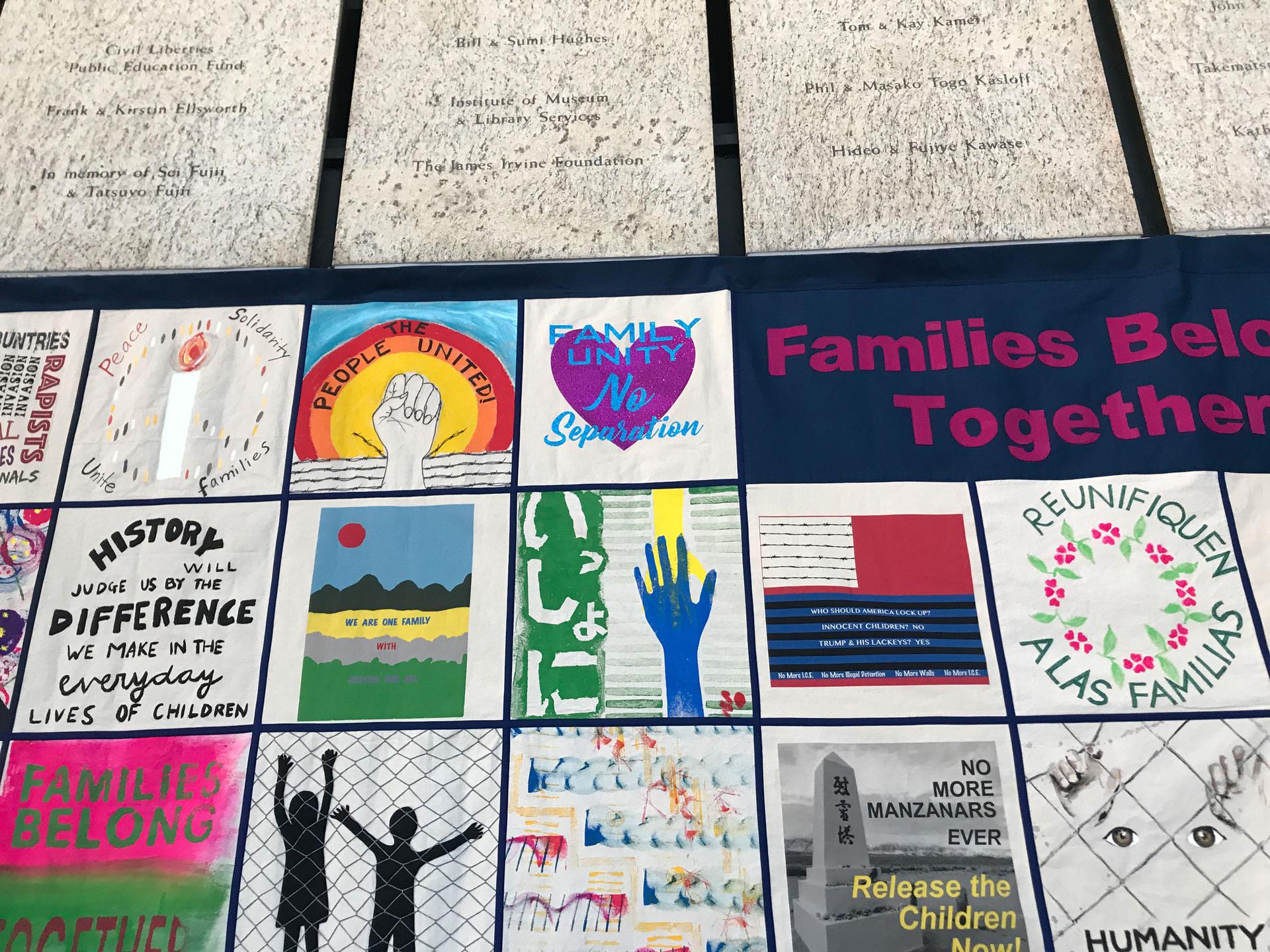

This February, the annual Day of Remembrance program at the Japanese American Museum in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo was packed with hundreds of people who came to memorialize the incarceration.

“We realize that with each passing year we have fewer and fewer who are able to attend,” the emcee announced. “But are there other incarcerees or veterans who are here today? If so, please stand. Anybody else? Please stand.”

Just a handful of elderly Japanese Americans stood, slowly, most with the help of walkers or the arms of people sitting next to them.

Linking the past to the present, the theme was “Behind Barbed Wire: Keeping Children Safe and Families Together,” which, according to the event description, “grew out of the scenes from last year that exposed the inhumane treatment of refugees and asylum seekers at our southern border as children were forcibly separated from their parents.”

Shooting photos for the Rafu Shimpo was the paper’s photo editor, Mario Gershom Reyes. An immigrant from Mexico, he has chronicled Japanese Americans’ lives for the past 30 years — ever since college, when he took what he thought would be a short-term gig working for the paper.

Related: Brought here by the US, Japanese Peruvians became ‘illegal’

“When I first started, of course, I didn’t know anything about this history,” he said. Then he got to know the stories of what had happened to Japanese Americans. “You just couldn’t believe that this government did this to its own citizens. That was the motive to keep doing what I’m doing.”

His earlier photos chronicled the rebuilding of Japanese American life in the decades after their release from the camps.

Often the only non-Asian person in the room, he has taken thousands of photos documenting the community’s fight for redress, the building of new institutions, and annual pilgrimages to incarceration camps.

And now, often, the memorial services.

Many among the generations that spent time incarcerated found it difficult to speak of that time. Reyes, the photographer, has found this an obstacle to capturing the stories he reports.

“A lot of these folks did not want to talk about it for the longest time. So a lot of folks ended up taking it to the grave with them.”

“A lot of these folks did not want to talk about it for the longest time. So a lot of folks ended up taking it to the grave with them,” he said. “It’s as if they don’t want to be identified as being Japanese.”

Yet, as people have entered their later years, he has also witnessed an increased willingness to talk, sometimes spurred by grandchildren asking questions.

These days at The Rafu Shimpo, the biggest news is often who died the night before — and more often than not it’s someone who spent time in an incarceration camp. As Muranaka and Reyes write the obituaries, they say they are often comforted to be able to draw on a record or past stories and photographs in a final tribute.

“They’re dying out, they’re passing on,” Reyes said. “But what’s gratifying is we’re recording their histories. And it’s not just us, there are many organizations that are recording their histories. So in a sense they will live on. Their story will live on. And their story will not be forgotten.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?