As the Supreme Court considers Trump’s travel ban, some want justices to remember a case they decided 74 years ago

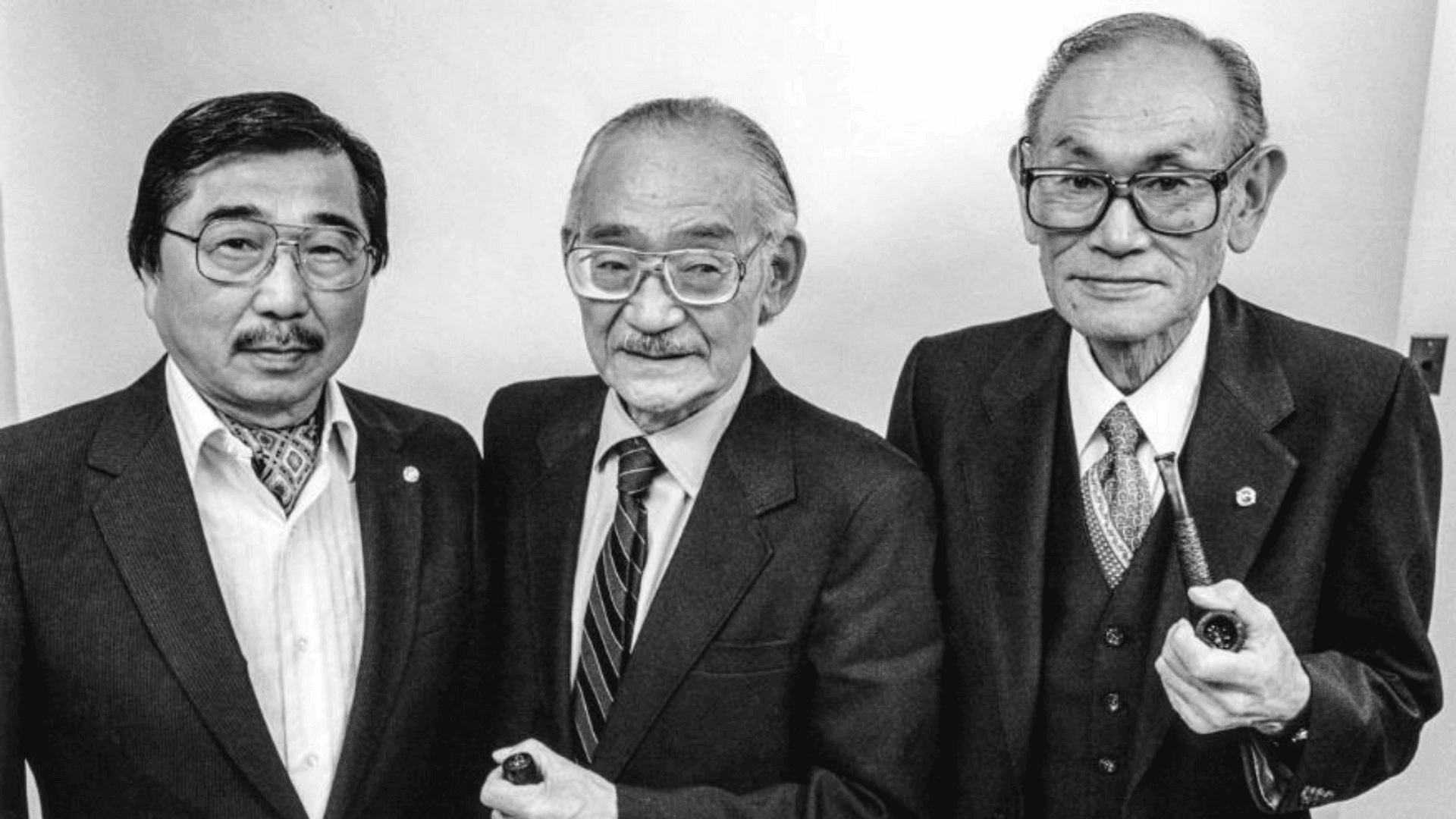

A 1983 portrait of Gordon Hirabayashi, left, Minoru Yasui, center, and Fred Korematsu at a San Francisco fundraiser to reopen their cases. Each man deliberately defied World War II-era orders placing curfews on Japanese Americans and sending them to concentration camps.

When the US Supreme Court hears oral arguments Wednesday in a legal challenge to President Donald Trump’s travel ban, the justices may think back to an infamous decision from 1944.

That year, the high court ruled in Korematsu v. United States that Japanese Americans could lawfully be sent to concentration camps during World War II. In a decision that legal scholars now almost universally view as shameful and wrong, the court accepted the government’s stance that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 authorizing the mass incarceration of more than 110,000 people — two-thirds of whom were native-born US citizens — was justified.

Though widely criticized, the decision has never been formally overturned.

On Wednesday, Karen Korematsu will be in Washington, DC, to attend oral arguments in honor of her late father, Fred Korematsu, the plaintiff in that case more than 70 years ago.

She has spent much of the past year, ever since Trump issued his first travel ban the first week of his presidency in January 2017, urging the Supreme Court not to repeat its World War II mistakes.

“The parallels are alarming,” says Korematsu, 67, who founded and runs the Fred T. Korematsu Institute in San Francisco. “In 1942, they said ‘military necessity’ as a justification, and now what the president is saying is ‘national security.’ Where’s the evidence that clearly shows that?”

We’ve been here before: Historians annotate and analyze immigration ban’s place in history

She has reason to ask. Nearly 40 years after her father lost his case before the Supreme Court, evidence was discovered that the government had suppressed, altered and destroyed evidence showing Japanese Americans were not, in fact, engaging in the espionage and disloyalty that the government said justified their incarceration. Lower courts considered that evidence in the 1980s to overturn the criminal convictions of three men — Fred Korematsu, Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui — who deliberately defied Roosevelt’s wartime orders. All three had served time in jail for their actions. And all three of their cases went to the Supreme Court, though Korematsu’s is the most well-known.

Karen Korematsu has joined with Holly Yasui and Jay Hirabayashi, children of the other two men. They have filed an amicus brief in the travel ban case urging the court to remember their fathers. They were joined by several Asian American, Latin American and African American groups.

Their fathers’ cases, the trio writes, “stand as important reminders of the need for courts — and especially this Court — to fulfill their essential role in our democracy by checking unfounded exercises of executive power. … By refusing to scrutinize the government’s claim that its abhorrent treatment of Japanese Americans was justified by military necessity, the Court enabled the government to cover its racially discriminatory policies in the cloak of national security.”

In the travel ban case, Trump v. Hawaii, the justices will consider the third and latest version of Trump’s executive order, in effect since December, which restricts travel for citizens of eight countries, six of them predominantly Muslim. (The countries are Syria, Iran, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, Venezuela and North Korea; Chad was recently removed from the list.) The court’s decision could have wide-reaching repercussions for executive power, particularly the president’s authority to protect the country by banning some foreigners from entry. It’s the justices’ final oral argument this session. And it’s long-awaited, as lower courts across the country have struck down much of Trump’s previous executive orders.

The justices may also consider how much weight to give anti-Muslim statements Trump made on the campaign trail.

“I’m calling, very simply, for a shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” Trump said in a December 2015 press statement. Then-candidate Trump recalled the incarceration of people with Japanese ancestry as an example of what he would eventually do as president.

“What I am doing is no different than what FDR — FDR’s solution for Germans, Italians, Japanese, you know, many years ago,” Trump told ABC News in an interview the next day. “This is a president who was highly respected by all. They named highways after him.”

But the government has sought to keep courts from considering what it considers “extrinsic material.”

“Impugning the official objective of a formal national-security and foreign policy judgment of the President based on campaign trail statements is inappropriate and fraught with intractable difficulties,” the government, represented by US Solicitor General Noel Francisco, wrote in its court brief.

The state of Hawaii is represented by Neal Katyal, a partner at the law firm Hogan Lovells in Washington. Katyal could have Korematsu on his mind Wednesday, too. As Acting Solicitor General in 2011, he issued a “confession of error” to publicly repudiate his predecessors’ participation in incarcerating Japanese Americans in the 1940s. The apology was built on a 1980s government investigation, which found Roosevelt’s incarceration order was based on “racial prejudice” and “wartime hysteria.” The US government paid reparations to tens of thousands of Japanese Americans over the next decade.

Toward the end of their lives, Korematsu, Yasui and Hirabayashi were each awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Despite the historical parallels, there are some important differences between Korematsu and Trump v. Hawaii.

For example, Roosevelt’s executive order dealt solely with people living inside the US, including US citizens, as Josh Blackman at South Texas College of Law Houston points out. Trump’s executive order applied to foreigners living abroad. Standards of constitutionality are different for the two groups.

Secondly, the military order Fred Korematsu violated in the early 1940s singled out Japanese Americans. None of Trump’s three executive orders refers to religion, though each largely restricts immigration for Muslims.

Dozens of civil rights organizations, religious groups, universities and states point this out in amicus briefs challenging the government’s stance. They call on the Supreme Court to safeguard constitutional protections against religious discrimination. The Japanese American Citizens League, in another brief referencing Korematsu, writes, “History teaches caution and skepticism when vague notions of national security are used to justify vast, unprecedented exclusionary measures that target disfavored classes.”

Trump’s supporters may disagree.

“The scope of this court’s decision here will have an impact on this (and future) president’s ability to protect our national security interests as he (and Congress) sees fit,” a group of national security experts wrote in their amicus brief. “At the end of the day, it is not the role of the judiciary to intercede in such matters, and this court should clearly say so.”

When it comes to national security and foreign affairs, the courts generally defer to the president and Congress, explains Richard Primus, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Michigan Law School.

“Korematsu was a case where the executive branch claimed a national security justification for what was actually a policy motivated by bigotry,” Primus says. “That’s what the travel ban is, too. Everyone knows that’s what this is. The question is just whether the courts will pretend not to know it.”

It’s impossible to say whether the Supreme Court justices will actually bring up Korematsu in oral arguments. At least two lower-court judges have drawn parallels to it in questioning government lawyers defending Trump’s travel ban. The government has distanced itself from the 1944 ruling.

But if Korematsu holds one lesson for the Supreme Court, it’s that the justices should closely scrutinize the government’s national security claims in light of the falsehoods uncovered decades after the fact, says Lorainne Bannai, director of Seattle University School of Law’s Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality. The center, along with the law firm Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, helped write the amicus brief on behalf of Karen Korematsu, Jay Hirabayashi and Holly Yasui.

“We’re not arguing the government is suppressing evidence,” says Bannai, who also served on the legal team that reopened their fathers’ cases in the 1980s. “But it’s a concern that the government is again saying, ‘We don’t need to give the court any justification for our actions.’”

There’s at least some reason for the courts to examine this ban closely: A leaked Department of Homeland Security report last February showed that citizenship is “unlikely to be a reliable indicator of terrorism threats to the United States,” undermining Trump’s public statement.

Karen Korematsu says she will be watching the justices’ words Wednesday.

“When my father’s Supreme Court case was heard on December 18, 1944, he was not at the Supreme Court,” she explains. “He’d been released from the concentration camp and was living in Detroit. So it’ll almost be like I’m representing him.”

Her counterparts say they’re hopeful, too.

“I hope that this ban will be struck down, that the court will stand on the side of equal justice for all and innocent until proven guilty and on the side of American democracy,” says Holly Yasui, 64. “What happened to our community was absolutely wrong, and for the most part legal scholars have said it’s wrong. I don’t want Muslims to have to wait 40 or 50 years for people to say this is wrong, too.”

She adds: “We can save a lot of suffering if the ban is struck down.”