With no Carnival, Haiti’s musicians lose more than their stage

Revellers dance during the celebration of Carnival in Jacmel, Haiti, Feb. 19, 2017.

If you turn on the radio in Haiti in the weeks leading up to Lent, you’ll be bombarded with calls for political and social change. The airwaves are filled with upbeat new party songs that musicians release for the Carnival season. Their lyrics hold up a mirror to society, mixing jabs at corrupt officials with calls for environmental protection and references to Haiti’s voodoo religious tradition.

But this year, there was no Carnival for the Carnival songs.

The past eight months have been marred by a series of anti-government protests over billions in missing funds related to the PetroCaribe agreement, an alliance between Venezuela and Caribbean countries including Haiti. People have been killed and dozens injured as demonstrators call for an independent probe into the money’s whereabouts and the ouster of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse. In the wake of protests last month that shut down parts of Port-au-Prince for more than a week, officials canceled Carnival. It was set to take place this week.

Related: Haiti vows to trim expenses and investigate PetroCaribe amid protests

The Carnival songs — always sharp — have been scathing this year.

“This is the first year where all the Carnival songs, or most of them, talk about the president himself,” says Carel Pedre, a well-known Haitian radio personality. “How he’s incompetent, how he’s a liar, how he’s making a bad move, how he’s not fit for the job.”

Pedre is the creator of PleziKanaval.com, a website that ranks Carnival songs in the weeks leading up to the biggest musical event of the year. It also features videos, artist interviews and an annual awards ceremony to honor the year’s top carnival songs. About 600 new songs were produced and submitted for airplay this year — several hundred fewer than in years past, but a healthy amount in light of recent unrest.

And in a country where music and politics are inextricably linked, that makes Pedre an expert on reading society’s pulse.

“I think PetroCaribe was the key word of this Carnival,” he said. “Every one of them mentioned PetroCaribe. All of them. Six hundred. Even some bands that used to be pro-government, they mentioned it anyway, maybe just to be in the moment.”

The songs are loaded with metaphors and double entendre.

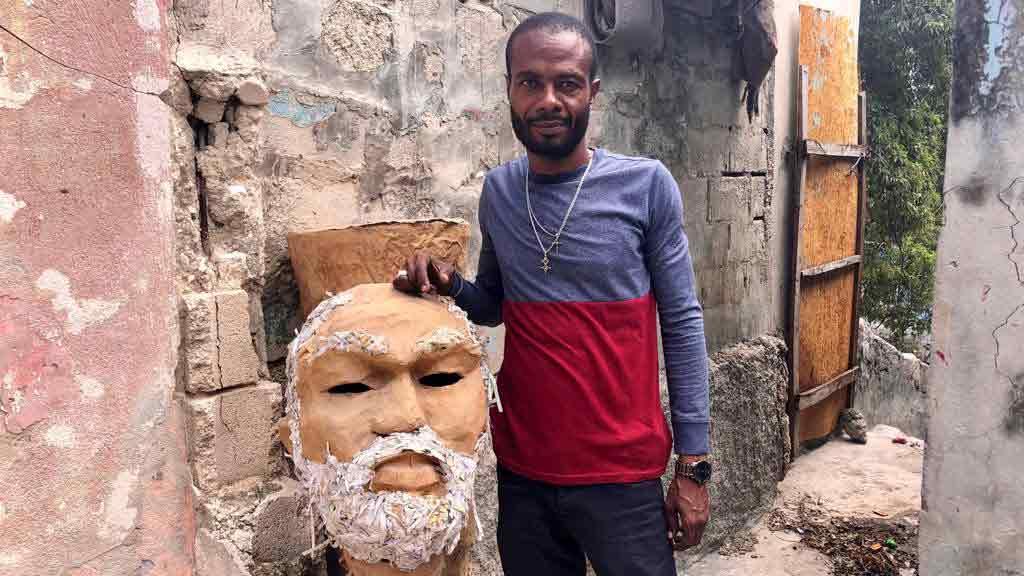

RAM, the legendary Haitian band that plays “musik rasin,” or roots music, refers to a nameless “they” reaching into the people’s “jakout,” a traditional bag used in Haitian voodoo ceremonies — and in this case, a nod to public funds. RAM’s tune is addressed to Ti Jean Petro, a Haitian voodoo spirit who partially shares a name with the Venezuelan oil company Haitians have evoked in their protests.

Boukman Eksperyans, another musik rasin band, sings of tying up the “thieves” who have stolen the country’s money in a song called “Nou Solid,” which loosely means, “we are strong.”

Other songs are more explicit. France-based Haitian solo artist Blayi One’s Carnival song, “Prezidan Pa Pridan,” translates to, “the president is reckless.” It begins with a demand for answers: “President, where is the money you were going to put in our pockets? / You killed me / You killed me with lies.”

Carnival — known in Haitian Creole as Kanaval — is supposed to be a nationwide catharsis. The streets fill with partygoers dressed in elaborate, colorful masks and costumes. They dance to the beat of the year’s new Carnival music, as well as traditional Haitian “rara,” where musicians beat on traditional tanbou drums and blow notes on tin trumpet-like instruments called konet. Cities nationwide hold their own Carnival festivals, with the biggest one taking place in Port-au-Prince.

For months leading up to Carnival, musicians compete to be selected as one of about 15 groups who are given a float to perform on at the three-day festival. Floats typically go to established groups guaranteed to draw fans and hype.

Carnival season is also when new artists try to catch a break: If they’re lucky, they’ll get some airplay, a bit of name recognition, and maybe land an interview or two. That’s why so many groups drop their new beats between December and early February. They might spend anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars recording their songs and producing a video — huge sums in a Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas and where much of the population lives on about $2 per day. The country has seen double-digit inflation since 2014.

That has put Carnival musicians in a tight spot: They may have still wanted to perform, even if they agree with an angry public that was largely against holding the annual nationwide party.

“What hurts the most is that I wasted a lot of time in the studio and got nothing for the fruits of my labor,” says Immacula Chery, a singer with Raram, a 26-year-old group whose name means “our ‘rara,’” referring to the Haitian music tradition.

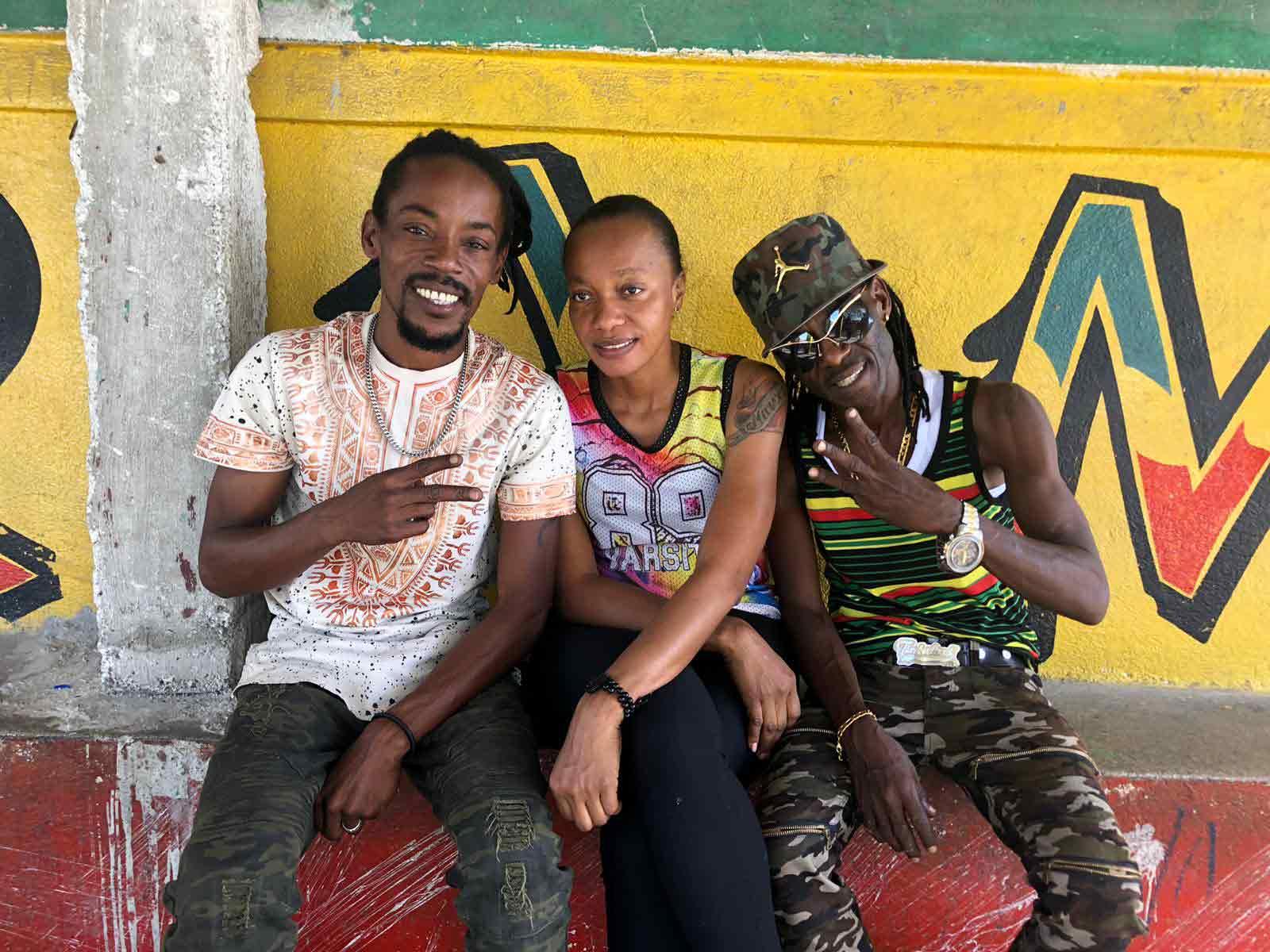

On Monday she sat with her two bandmates — Coicou Yves Mary, known as Samba Coicou, and Francois Louis Dieu, known as Maestro Francisco — on their empty neighborhood stage on the streets of Bel Air, a poor area of Port-au-Prince also known for being home to artists and musicians. There were few signs it was a national holiday.

Chery estimates the band spent about $3,000 in studio time and $4,000 on equipment and production for their carnival music video, plus another $700 for costumes and backup dancers. Had they performed on a Carnival float this week, they would have gotten paid from the government and the event’s private-sector sponsors. They would have made back what they spent and more.

Bands have also lost other gigs as a violent round of chaos last month shut down parts of the capital for more than a week.

“These are bands that don’t go out of the country to play,” Pedre explains. “And especially when they don’t play in Carnival, it’s like they lost three months of the year, and they were budgeting on that money.”

Haiti’s fledgling tourism industry has taken a hit, too. In Port-au-Prince, hotels are usually packed with visitors and members of the Haitian diaspora who fly home for Carnival. But this year, hotels have seen cancelation after cancelation. Hotels located around Champ de Mars, the downtown square located along the festival route, are hosting few guests besides a handful of foreign journalists — a universal sign of trouble.

It’s potentially erasing years of effort and millions of dollars Haiti has poured into remaking its image after a devastating 2010 earthquake that killed some 300,000 people and injured 1.5 million.

The earthquake — often referred to here simply as “the catastrophe” or goudou-goudou, for the roaring sound made when buildings shook — was the last time many people can recall the government canceling Carnival. Before that, the festival was last called off in 1986 after the fall of the 30-year Duvalier family dictatorship.

“We’re being tested. Our resolve is being tested. Politics has consumed everyone.”

Those events are the only way to measure the severity of the present moment, says Richard Morse, the founder of the band RAM and manager of the beautiful Hotel Oloffson in central Port-au-Prince.

“If you want to stretch, you could say the social-political situation in Haiti is that bad,” he said. “You don’t have half a million people living in the street like they were after the earthquake. But if you want to explain it to someone you’d say, ‘Things got so bad in Haiti that there was no Carnival.’”

As for his hotel, he’s had to let go half his staff of roughly 22, many of whom had been working there for years.

“We’re being tested,” he said. “Our resolve is being tested. Politics has consumed everyone.”

Amy Bracken contributed to this report. Bracken and Karas reported from Port-au-Prince.