Why US-backed aid to Venezuela harkens back to a dark history of covert operations

Two women carry the coffin of a child killed in a Contra landmine in Managua, July 4, 1986. Thirty-one unarmed civilians, including women and children, were killed when the truck they were riding in struck a Contra landmine. The truck was carrying a 50-gallon barrel of gasoline.

A push to bring US-backed food and medicine into Venezuela ended in chaos on Feb. 23, as trucks carrying supplies across the Colombia-Venezuela border were set aflame and several hundred people are reported injured in clashes. The humanitarian aid could have brought some relief to Venezuelans facing a humanitarian crisis — 90 percent live in poverty, and the dire shortages have forced millions to flee. But the move was also a confrontation over Venezuela’s political leadership and international backing — and brings up a history of American involvement in the region.

Related: Malnourished Venezuelans hope urgently needed aid arrives soon

Venezuela’s opposition leader and self-appointed interim President Juan Guaidó supported the ill-fated move to bring US aid into the country. Supplies were forced back by Venezuela’s military, under the direction of embattled President Nicolás Maduro. Maduro has been accused of rigging his re-election in 2018, and has refused US assistance, arguing that the US is trying to destabilize his socialist government.

Many others, from leaders of international aid organizations to scholars, have said US-backed aid uses Venezuelan suffering as a pawn to further American political goals, including ousting Maduro.

The standoff over American aid harkens back to a sordid history of US intervention and “democracy promotion” in Latin America, which has been fraught with links to human rights abuses.

This history was re-examined in a House Foreign Relations Committee on Feb. 13 when Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) challenged Elliott Abrams, recently-appointed US Special Representative for Venezuela, about his controversial role while serving as President Ronald Reagan’s former assistant secretary of state for human rights and humanitarian affairs. In a heated exchange that went viral, Omar raised issues of Cold War-era human rights violations in Latin America that occurred under Abrams’ watch in the 1980s, and asked about US action in Venezuela today.

“Will you make sure that human rights are not violated?” she asked. Abrams avoided a direct answer: “The entire thrust of American policy in Venezuela is to support the Venezuelan people’s efforts to restore democracy to their country,” he said.

Related: Stalled humanitarian aid to Venezuela ‘is a trap,’ says ex-Maduro staffer

Some historians argue US foreign policy in Latin America during the Cold War was less about “promoting democracy” than it was about “halting communism” in the region. The power struggle between the US and Soviet Union in the Cold War is often understood as one between “democracy” and “communism,” but this overlooks historical shared interests between free-market capitalism and right-wing dictatorships.

To stave off Soviet influence in growing communist and socialist movements in Latin America, the US supported dictatorships in Chile, Argentina, Peru, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala and Uruguay, among others. The promotion of US capitalist interests in Latin America often came at the cost of democratic institutions — including fair elections and free speech — and with brutal consequences for human rights.

During his tenure in the Reagan administration, Abrams not only knew of but actively endorsed and enabled widespread human rights abuses in the region in the 1980s under these dictatorships. His responses at the Feb. 13 Congressional hearing have led to concerns that he is not opposed to using the same tactics to “promote democracy” in Venezuela today.

The Massacre of El Mozote

When Omar questioned Abrams in Congress on Feb. 13, she referred to the massacre of El Mozote, El Salvador, and his past guilty plea for withholding information from Congress and his testimony dismissing the El Mozote report as communist propaganda.

Over the course of the 20th century, El Salvador was wracked by political and economic instability characterized by coups, revolts and dictatorships. Abrams was deeply involved in the US response to the 1972-1992 Salvadoran Civil War that erupted between the right-wing military government and a coalition of left-wing guerrilla groups and killed more than 75,000 people between 1980 and 1992.

In 1981, a massacre took place in the small village of El Mozote. Suspected of communist loyalties, the village was targeted by the Salvadoran army as part of a scorched-earth campaign to eliminate guerrillas fighting the country’s right-wing military dictatorship.

According to the UN Truth Commission, more than 800 civilians — mostly children and women, many who were raped beforehand — were murdered with US-supplied automatic M-16 rifles.

The massacre became emblematic of Cold War violence in Latin America.

The 1992 Chapultepec Peace Accords formally ended the conflict and established a democratic constitutional republic, which remains the current form of government.

For over a decade both El Salvador and the US denied reports of the massacre as gross exaggerations, and the US continued to supply the country with military aid and weapons.

At the time, Abrams defended the Salvadoran Army and described US foreign policy in El Salvador as a “fabulous achievement.” In his 1982 testimony to Congress, Abrams said that the reports of the massacre of El Mozote were “not credible” and framed the issue in terms of a country’s democratic struggles against dictatorship: “We must help El Salvador move forward toward democracy as long as its people are willing to risk their future in this struggle.”

In 2011, the Salvadoran government officially apologized for the tragedy, but the US has made no official comment. Documents recently released under the Freedom of Information Act indicate that the US government, under Abrams’ guidance, knew of human rights atrocities at the time, but still chose to support the Salvadoran military.

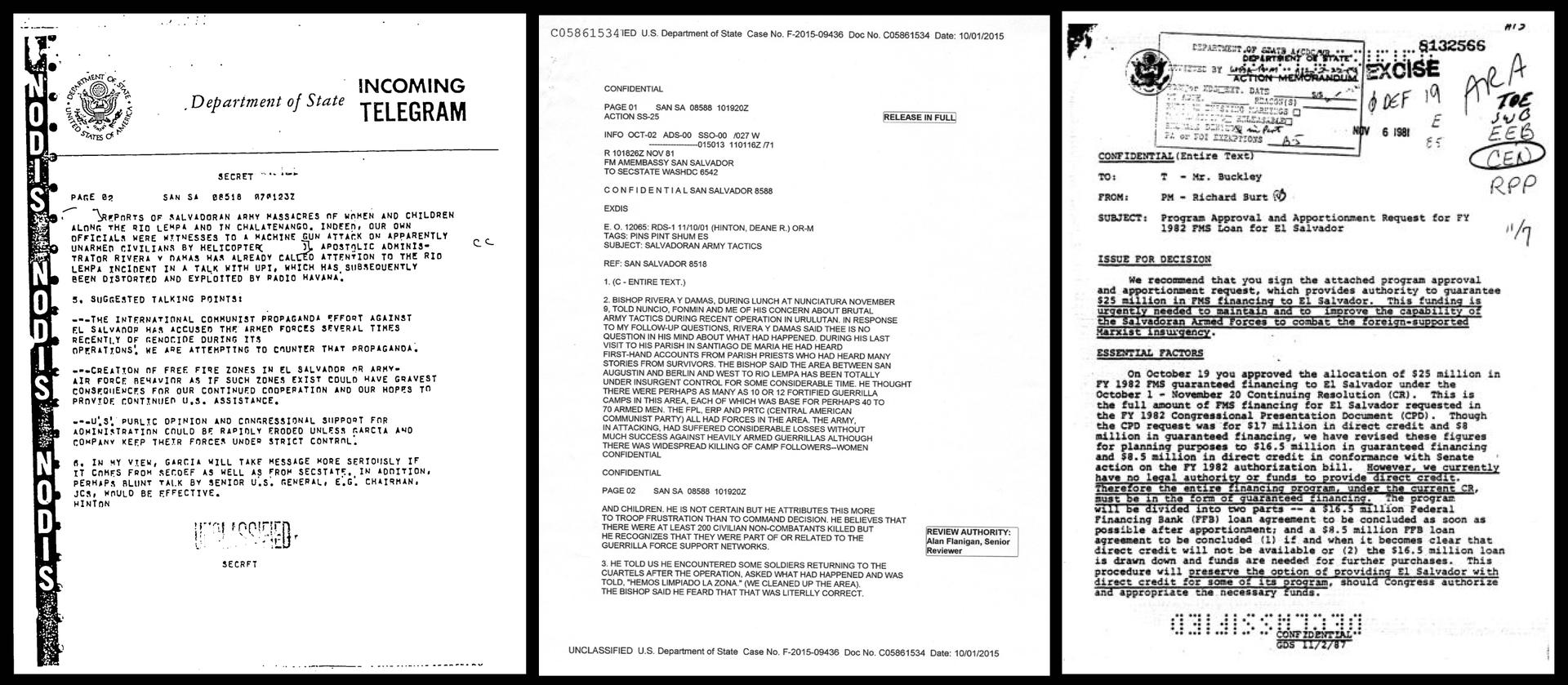

One telegram to the US Department of State dated November 1981 reads: “[We] have detailed reports of Salvadoran Army massacres of women and children … Indeed, our own officials were witnesses to a machine gun attack on apparently unarmed civilians by helicopter.”

Another sent days later reads: “[T]here were at least 200 civilian non-combatants killed.” Later that same week, the US expressed its intention to move forward with a $25 million loan to finance purchase of M-16 rifles, machine guns, ammunition and vehicles for the Salvadoran military.

In response to Omar’s question of whether he stood by his claim that El Salvador represents a “fabulous achievement” Abrams responded, “From the day [US-backed] President José Duarte was elected in a free election, to this day, El Salvador has been a democracy. That’s a fabulous achievement.”

Related: As Venezuela’s crisis worsens, thousands more flee to neighboring Colombia seeking relief

The Iran-Contra affair

Abrams has also faced backlash for his coverup role in the Iran-Contra affair, a scandal in which Reagan administration officials violated an Iranian trade embargo to illegally fund “Contras” or counter-revolutionaries in Nicaragua.

For much of the 20th century, Nicaragua was ruled by the Somoza family — a right-wing dynasty friendly to US economic interests. But in 1979 a left-wing coalition of students, farmers, small business owners and religious groups launched the Sandinista Revolution to overthrow the Somoza dictatorship. Then-President Anastasio Somoza DeBayle resigned, leaving the country in economic ruins. In control, the Sandinistas enacted massive agrarian reforms to subsidize spending on education and health care.

By 1981, the former USSR began donating significant aid to the Sandinistas and the US began supporting the counter-revolutionaries — turning the civil war into a proxy struggle between communist and capitalist interests.

But the Contras — backed by the US government — failed to win widespread popular support or military victories within Nicaragua. By 1985, public opinion in the US also turned against them, leading Congress to cut off all funds supporting their fight against the Sandinistas.

Abrams and other senior officials in the administration continued to finance the Contras against the wishes of Congress. They participated in the illegal arms transfer — widely known as the Iran-Contra affair — by violating the embargo passed after the 1979 Iranian Revolution to selling arms to Iran. They did this by raising the revenue banned by Congress to fund Contra military efforts. Abrams later withheld information about his role in the scandal in a 1986 Congressional hearing.

The Contras, armed and trained by the CIA, committed human rights violations and systemically used terrorist tactics to destabilize the Sandinista government. Americas Watch, later part of Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations Refugee Agency accused the Contras of kidnapping, torturing and executing civilians — including children — captured in combat, raping women and targeting health care clinics and workers for assassination.

With 50,000 dead and basic infrastructure destroyed, the Contra War in Nicaragua ended with the democratic election of a Contra- and US-backed party, and in 1990 the country embraced new policies that opened domestic markets to US economic interests.

Vision for Venezuela?

The clashes between Maduro and Guaidó supporters over American aid raises the inevitable question: Will US aid lead to US intervention? Trump has already sent strong messages to Maduro and his backers, warning that military options remain on the table if a peaceful transition of power does not take place, though some regional experts are skeptical. Venezuelans have been dealing with crisis conditions for two decades, but this is the first time the US has made overt threats of military involvement.

While humanitarian aid would help desperate Venezuelan people in the short run, many have flagged it as a political ploy. Both the United Nations and the International Committee for the Red Cross declined to collaborate with the US, arguing that humanitarian missions should not be linked to political power plays. And with the US’s history of aiding regime change in Latin America — and some of the same key players involved again — the criticism is valid.

Related: Thousands mobilize, some soldiers defect, but Venezuelan aid push ends in chaos

Editor’s note: Kelsey Gilman is a graduate student at the University of Washington’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, where she is completing her doctoral degree in Latin American and Indigenous studies. She is a graduate teaching and research assistant. Her research explores the politics of Indigenous intercultural higher education in Ecuador.