South Korea’s latest big export: Jobless college graduates

A jobseeker looks at a booth during the 2018 Japan Job Fair in Seoul, South Korea, Nov. 7, 2018.

Cho Min-kyong boasts an engineering degree from one of South Korea’s top universities, a school design award and a near-perfect score in her English proficiency test.

But she had all but given up hope of finding a job when all her 10 applications, including one to Hyundai Motor Co., were rejected in 2016.

Help came unexpectedly from neighboring Japan six months later: Cho got job offers from Nissan Motor Co. and two other Japanese companies after a job fair hosted by the South Korean government to match the country’s skilled labor with overseas employers.

“It’s not that I wasn’t good enough. There are just too many job seekers like me, that’s why everyone just fails,” said the 27-year-old, who now works in Atsugi, an hour southwest of Tokyo, as a car seat engineer for Nissan.

“There are numerous more opportunities outside Korea.”

Related: K-pop stardom lures Japanese youth to Korea despite diplomatic chill

Facing an unprecedented job crunch at home, many young South Koreans are now signing up for government-sponsored programs designed to find overseas positions for a growing number of jobless college graduates in Asia’s fourth largest economy.

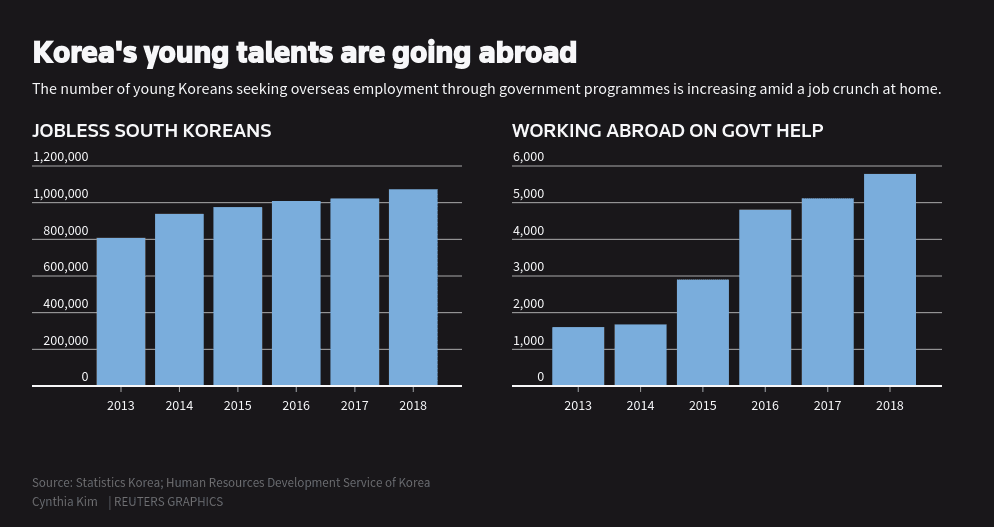

State-run programs such as K-move, rolled out to connect young Koreans to “quality jobs” in 70 countries, found overseas jobs for 5,783 graduates last year, more than triple the number in 2013, its first year.

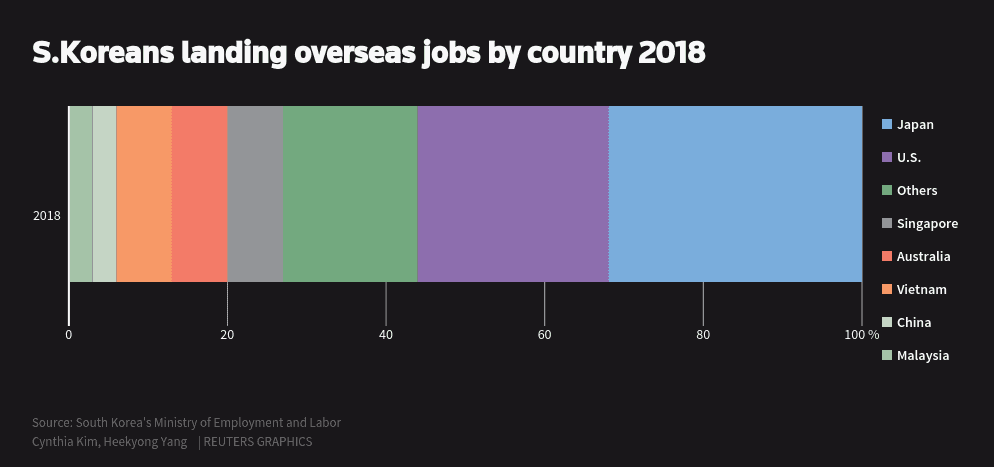

Almost one-third went to Japan, which is undergoing a historic labor shortage with unemployment at a 26-year low, while a quarter went to the United States, where the jobless rate dropped to the lowest in nearly half a century in April.

Related: 60 years before BTS, the Kim Sisters were America’s original K-pop stars

There are no strings attached. Unlike similar programs in places such as Singapore that come with an obligation to return and work for the government for up to six years, attendees of South Korea’s programs are neither required to return, nor work for the state in the future.

“Brain drain isn’t the government’s immediate worry. Rather, it’s more urgent to prevent them from sliding into poverty” even if it means pushing them abroad, said Kim Chul-ju, deputy dean at the Asian Development Bank Institute.

In 2018, South Korea generated the smallest number of jobs since the global financial crisis, only 97,000.

Nearly one in five young Koreans was out of work as of 2013, higher than the average 16% among the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In March, one in every four Koreans in the 15-29 age group was not employed either by choice or due to the lack of jobs, according to government data.

Labor mismatch

While India and other countries face similar challenges in creating jobs for skilled labor, the dominance of family-run conglomerates known as chaebol makes South Korea uniquely vulnerable.

The top 10 conglomerates, including world-class brands such as Samsung and Hyundai, make up half of South Korea’s total market capitalization.

But only 13% of the country’s workforce is employed by firms with more than 250 employees, the second lowest after Greece in the OECD, and far below the 47% in Japan. “The big companies have mastered a business model to survive without boosting hiring,” as labor costs rise and firing legacy workers remains difficult, said Kim So-young, an economics professor at Seoul National University.

Related: Trump’s trade war with China drives silent wedge between US and South Korea

Yet while increasing numbers of college graduates are moving overseas for work, South Korea is bringing in more foreigners to solve another labor problem — an acute shortage of blue collar workers.

South Korea has the most highly educated youth in the OECD, with three-quarters of high school students going to college, compared with the average of 44.5%.

“South Korea is paying the price for its overprotection of top-tier jobs and education fervor that produced a flood of people wanting only that small number of top jobs,” said Ban Ga-woon, a labor market researcher at state-run Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training.

Even amid a glut of over-educated and under-employed graduates, most refuse to “get their hands dirty,” says Lim Chae-wook, who manages a factory making cable trays that employs 90 people in Ansan, southwest of Seoul. “Locals simply don’t want this job cause they think its degrading, so we’re forced to hire a lot of foreign workers,” Lim said, pointing to nearly two dozens workers from the Philippines, Vietnam and China working in safety masks behind welding machines.

Related: A new book suggests AI and robots will take jobs — but make the world better

In the southwestern city of Gwangju, Kim Yong-gu, the chief executive of Kia Motor supplier Hyundai Hitech, says foreign workers are more expensive but he has no choice as he can’t find enough locals to fill vacancies.

“We pay for accommodation, meals and other utility costs in order not to lose them to another factory,” said Kim. Out of a staff of 70, 13 are Indonesian nationals, who sleep and eat at a building next to his factory.

No happy ending for everyone

For those who escaped Korea’s tough job market, not all has been rosy.

Several people who found overseas jobs with government help say they ended up taking menial work, such as dishwashing in Taiwan and meat processing in rural Australia, or were misinformed about pay and conditions.

Lee Sun-hyung, a 30-year old athletics major, used K-move to go to Sydney to work as a swim coach in 2017, but earned less than $A600 ($419) a month, one-third what her government handlers told her in Seoul.

“It wasn’t what I had hoped for. I could not even afford to pay rent.”

“It wasn’t what I had hoped for. I could not even afford to pay rent,” said Lee, who ended up cleaning windows at a fashion store part-time before she returned home broke less than a year later.

Officials say they are making a “black list” of employers and improving the vetting process to prevent recurrence of such cases. The labor ministry also established a “support and reporting center” to better respond to problems.

Many on the programs lose touch once they go overseas. Almost 90% of the graduates who went abroad with the government’s help between 2013-2016 didn’t respond to the labor ministry’s requests about their whereabouts or changed their contact details, a 2017 survey showed.

Still, the grim job market at home is driving more Koreans to the program every year. The government has also increased relevant budget to support rising demand — from 57.4 billion won ($48.9 million) in 2015 to 76.8 billion won (about $64.5 million) in 2018, data released by lawmaker Kim Jung-hoon shows.

“The government isn’t scaling up this project to the extent we would worry about brain drain,” said Huh Chang, head of the development finance bureau at South Korea’s finance ministry, which co-manages state-run vocational training programs with the labor ministry. Rather, the focus was on meeting growing demand for overseas experience given so many graduates are outside the workforce, Huh added.

Related: Automation could have a disproportionate effect on women’s jobs

A hopeful scenario would be for the economy to one day make use of the resources these graduates bring home as experienced returnees, Huh said.

For 28-year-old K-move alumni Lee Jae-young, that feels like a distant prospect.

“The one year abroad added a line in my resume, but that was about it,” said Lee, who returned to Korea in February after working as a cook at the JW Marriott hotel in Texas. “I’m back home and still looking for a job.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?