Hundreds of Haitians took to the streets Friday to demand the release of a final audit report accusing Haiti’s political class of embezzling or misusing well over a billion dollars received through Venezuela’s discounted PetroCaribe oil alliance program.

“Mare yo!” they chanted in downtown Port-au-Prince — Haitian Creole for “handcuff them.”

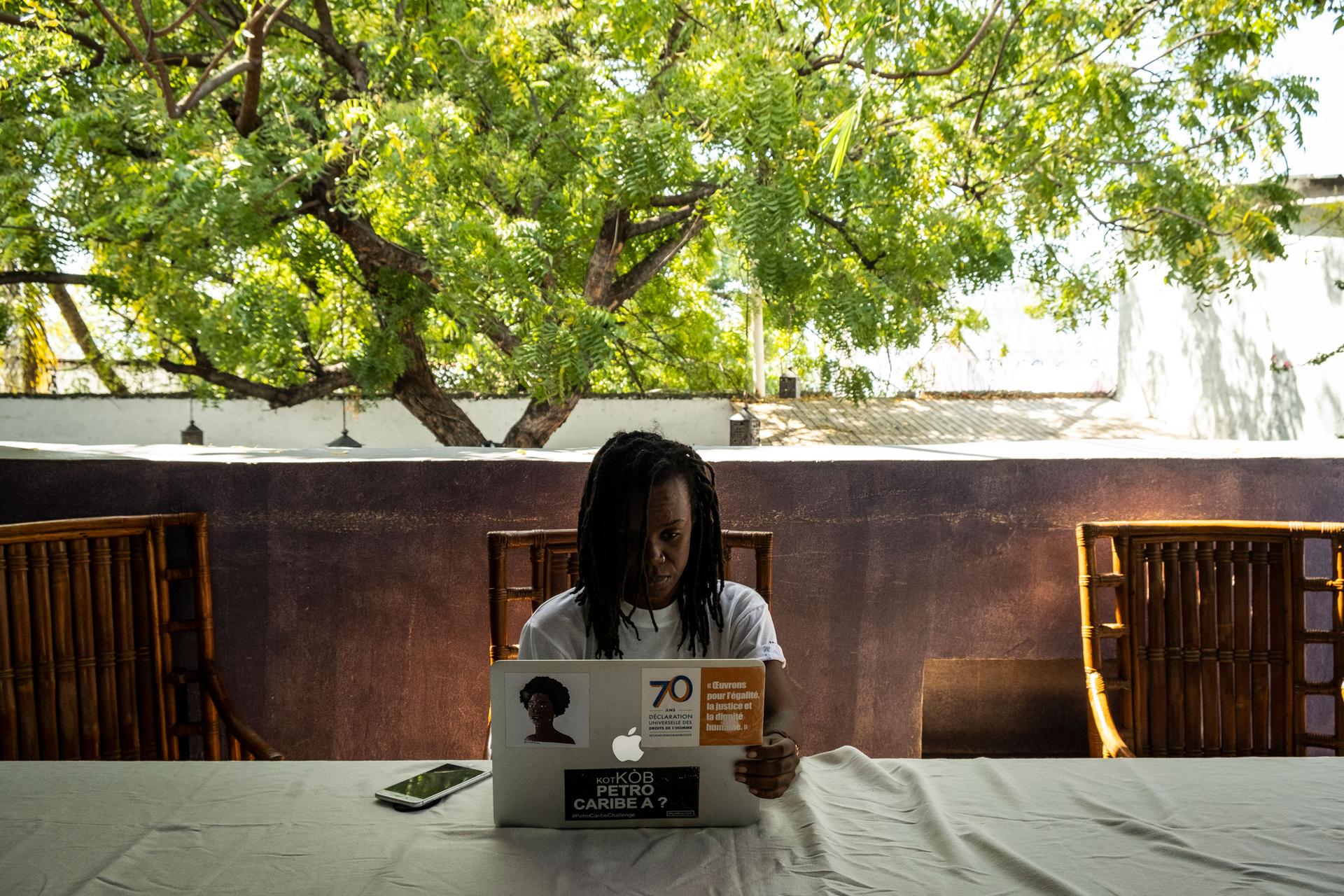

The resistance underway in Haiti started, as modern-day revolutions do, on Twitter. It was August 2018, and tensions were still high after the Haitian government announced — then retracted — a plan to raise the price of fuel by as much as 51%. Gilbert Mirambeau Jr., a 35-year-old Haitian filmmaker and writer, tweeted a photo of himself blindfolded, holding a handwritten cardboard sign reading, “Kot Kòb Petwo Karibe a???” or “Where is the PetroCaribe money???”

“I felt betrayed,” he said last month in Port-au-Prince. “People are literally dying in Haiti because they can’t eat, and they’re going and spending the money that was supposed to help us.”

Related: A family split between the US and Haiti dreads looming loss of legal status

The blindfold was meant to evoke a kidnapping victim — a metaphor, Mirambeau said, for the people of Haiti being held hostage by their corrupt government — as well as the Greek goddess Themis, who raises the scales of justice with her eyes covered to ensure justice is meted out objectively.

Within two days of his tweet, the hashtag #KotKòbPetwoKaribea exploded as thousands of Haitians tweeted photos of themselves holding the same sign. In some Port-au-Prince neighborhoods, it was spray-painted onto every street corner and billboard. The tweets and street protests spread to the Haitian diaspora in Boston, Miami, Montreal and Paris. And #KotKòbPetwoKaribea became the rallying cry for a new movement unlike any other in Haitian history — one led by youth armed with smartphones, who are wielding social media to speak out against impunity and demand transparency from political leaders accustomed to obscuring their corruption behind Haiti’s dysfunctional institutions.

They call themselves the Petrochallengers.

The core group is comprised of 20- and 30-somethings who came of age after Haiti’s devastating 2010 earthquake, from which the country has still hardly recovered. More than $13 billion in postquake aid flowed into the country, though today there’s little to show for it. The misused PetroCaribe funds are viewed as another missed opportunity for Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

For months, they’ve protested the results of two reports — one released in 2017 and another in January — that detail how the PetroCaribe money was misused. The program, the result of an agreement with Venezuela reached in 2006, was meant to give Haiti petroleum at preferential payment rates that would allow the Haitian government to finance development projects — such as housing, schools, hospitals and roads — through domestic oil sales.

Related: With no Carnival, Haiti’s musicians lose more than their stage

But the reports show many of those projects don’t exist, though well over a billion dollars was paid out. And they implicate 15 former ministers and senior officials along with a company once headed by President Jovenel Moïse.

The latest report was supposed to come out by the end of April. Last week, the audit court announced it would delay it until mid-May.

‘The Haiti we want’

On a Tuesday afternoon last month, a dozen Petrochallengers gathered for their weekly meeting in a colorful, art-filled cafe near central Port-au-Prince. Known for attracting activists, expats and an LGBTQ crowd, it’s become the de facto headquarters for their movement.

Édith Piaf’s “La Vie en Rose” wafted across their back-porch meeting space as attendees filed in, several of them dressed in business attire from their day jobs. The table was soon littered with laptops, smartphones and bottles of Prestige, Haiti’s national beer.

Among them was Emmanuela Douyon, a 29-year-old researcher who is starting her own think tank focused on economic development. She was mobilized by Mirambeau’s Twitter challenge and has delayed the launch of her organization to devote more time to Petrochallenge activism.

Uprisings in Haiti tend to have the effect of simply ousting one president or prime minister and replacing him with another, she explained.

“But now, the PetroCaribe challenge is not something against a president. It’s not against a dictatorship. It’s people asking for accountability, and this is a huge problem in Haiti. But it’s been a long time since we have had so many people coming together to ask for it. I think this is really new.”

“But now, the PetroCaribe challenge is not something against a president. It’s not against a dictatorship,” she said. “It’s people asking for accountability, and this is a huge problem in Haiti. But it’s been a long time since we have had so many people coming together to ask for it. I think this is really new.”

The Petrochallenge movement is comprised of two groups: Nou Pap Dòmi, or “We keep our eyes open,” which is focused on government accountability in the short term; and Ayiti Nou Vle A, or “The Haiti we want,” a group that encourages ordinary citizens to get involved in shaping Haiti’s long-term future by encouraging civic engagement, online and offline. Both groups started in the wake of Mirambeau’s tweet.

For inspiration, the Petrochallengers have looked to other youth-led movements around the world that used social media, such as the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street and Y’en a Marre, a Senegalese movement created by young rappers and journalists to protest ineffective government and register youth to vote. They’ve also looked to France’s Yellow Vest protests, which President Emmanuel Macron responded to just last week.

Social media is a key component of the Petrochallenge movement, said Gaëlle Bien-Aimé, 31, a Haitian women’s rights activist, comedian and Petrochallenger. For example, people have tweeted photos of vacant lots and skeletal structures where some of the nearly $2 billion in PetroCaribe funds were supposed to have been spent.

“It’s not the first time money has disappeared like this or been wasted. But this is one of the biggest financial scandals in a time when information is not hidden. Everything is posted on WhatsApp, Twitter and other social media.”

“It’s not the first time money has disappeared like this or been wasted,” she said. “But this is one of the biggest financial scandals in a time when information is not hidden. Everything is posted on WhatsApp, Twitter and other social media.”

‘This will make people believe in Haiti again’

The Petrochallengers have pledged to keep protesting until those named in the report are put on trial for the money they stole. They’ve said they’ll keep going until they can vote in a new government, one that answers to the Haitian people. And they want the trial to take place in Haiti, to be overseen by the Haitian judiciary.

“I think if we have the PetroCaribe trial and some really, really, really powerful people go to prison or pay for what they did, then this will show that in Haiti, we too can fight corruption,” Douyon said. “I think it will show us — for the younger generation, this is what we can do. If we reach this, people will start believing that we can create jobs. We can develop Haiti.

“If we have at least the trial, this will make people believe in Haiti again,” she added. “Because for now, no one does.”

The difficulty, however, will be ensuring their activism leads to accountability. The Petrochallenge movement is not aligned with any political party — and that’s by design. They want it to be as inclusive as possible.

Some observers say that could be their downfall.

“This movement is interesting because they tend to be neutral in terms of politics,” said Robert Fatton, a Haiti analyst and politics professor at the University of Virginia. “In one way, that gives them strength. But it also gives them a rather weak hand, because the people who are accused have more power than the people who are accusing them. We’ll see what will happen, whether political parties in the opposition are going to hijack the movement for their political purposes.”

Politicians are already tapping into the discontent. In February, the Democratic and Popular Sector, an alliance of Haitian opposition groups that want to oust the president, promoted protests that turned violent and lasted 10 days, bringing the country to a standstill. Twenty-six people died, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Private businesses were set on fire and looted. And though the protests drew from the same deep well of anger beneath the Petrochallenge movement, they weren’t organized by the same groups of which Mirambeau, Douyon and Bien-Aimé are part.

The Petrochallengers’ insistence on staying out of politics may not be enough, said Jocelyn McCalla, a longtime Haitian human rights advocate based in New York.

“Where they are weakest is in believing that popular pressure alone is going to force the people — the people implicated in the report as well as the people who have influence over the judicial system — to act.”

“Where they are weakest is in believing that popular pressure alone is going to force the people — the people implicated in the report as well as the people who have influence over the judicial system — to act,” he said. “They have to take one more step. And that more that, one more step is being more politically engaged.”

In the Petrochallengers’ view, the pressure they’ve exerted from outside politics has already brought about some change. Their biggest impact has been heightened awareness of how public funds are spent, said Jeffsky Poincy, a 32-year-old economist and Petrochallenger.

“People didn’t know what was happening in the public administration in Haiti, nor with the PetroCaribe funds. Now, they do,” he said. “Now, the government cannot take any action without taking into account PetroCaribe.”

In addition, amid the demonstrations, Haitian lawmakers have forced out two prime ministers and their governments in the span of six months. A new prime minister, Jean Michel Lapin, took the job last month with a goal to quell disagreement among various political factions.

The next generation

Haiti is a young country: More than half the population of about 11 million is under 25 years old, according to World Bank figures. More than 6 million people live below the poverty line of $2.41 per day. They are plagued by a weakening local currency, years of double-digit inflation and widening inequality.

Not only that: Access to clean drinking water has always been rare, and power outages have grown more frequent in the past few months as PetroCaribe woes have the country scrambling for ways to pay for fuel. Gang violence is on the rise.

Then, of course, there’s the corruption. Haiti ranks 161 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

“The country is sitting on top of a volcano of discontent. So many issues are incredibly pressing. To send your kid to school — you can’t do that anymore. Teachers have not been paid, and the price of transportation has increased significantly. It’s impossible to sustain yourself. It’s really a very, very desperate situation.”

“The country is sitting on top of a volcano of discontent,” said Fatton, the Haiti analyst from the University of Virginia. “So many issues are incredibly pressing. To send your kid to school — you can’t do that anymore. Teachers have not been paid, and the price of transportation has increased significantly. It’s impossible to sustain yourself. It’s really a very, very desperate situation.”

Without basic public services and infrastructure, let alone opportunities for social mobility, many young people feel their futures have been stolen.

That’s why the Petrochallenge movement has exploded, said James Beltis, a 36-year-old sociologist and co-founder of Nou Pap Domi and its spokesperson. The group organized Friday’s protest and others last fall.

“For me, it’s a big, historical moment because normally, the Haitian people are victims of political manipulation,” Beltis said. “I feel I’m participating in destroying a system that’s existed for hundreds of years and turned Haiti into a country of beggars. And I’m participating in the construction of a new Haiti.”

The fight is personal for Beltis. He is the father of twins, a boy and a girl. His wife gave birth to them in the United States because of medical complications — and his son, Adam, resides permanently in an Orlando, Florida, medical facility because there’s no hospital in Haiti equipped to handle his life-threatening respiratory issues.

The twins turned 4 last week, and Adam has never been to Haiti.

“I have to take out money every four to six months to travel to the US to see my child. He could be here if the men in the government didn’t steal the $4 billion that was there for development. There would’ve been a hospital here. And this is not the case.”

“I have to take out money every four to six months to travel to the US to see my child,” Beltis said. “He could be here if the men in the government didn’t steal the $4 billion that was there for development. There would’ve been a hospital here. And this is not the case.”

A wake-up call

The Petrochallengers are the latest in a long line of Haitian resistance movements. Haitian schoolchildren grow up learning how their ancestors led the world’s first successful slave rebellion and founded a republic in 1804.

Its more recent history is marked by coups, notably the overthrow of the Duvalier “Papa Doc” and “Baby Doc” dictatorship in 1986. Haiti has hardly experienced a quiet period since, and the past three decades have seen frequent political interventions by the United States and United Nations. Many of the elite families that dominated the economy during the Duvalier era still dominate today.

That’s why many Haitians don’t feel they’re in control of their country’s destiny.

Moïse, the current president, was unpopular long before the PetroCaribe scandal: He took office in February 2017 after a contested election in which only 20% of the electorate voted. Many within the recent protests have called for his ouster.

The PetroCaribe scandal had been simmering for years. International and local watchdog groups long suspected the funds were being misused. Then two reports gave them proof: an October 2017 report by a special commission of Haiti’s Senate, which covered the period from 2008 to 2016, then a January 2019 report by Haiti’s audit court.

The muted, initial reaction to the 2017 report shows how Haitians have become numb to the depths of corruption. It would be several more months until Mirambeau tweeted and got people angry — and prompted them into the streets.

“People needed a wake-up call,” Mirambeau said. “The movement gave them that.”

The reports contain hundreds’ of pages worth of public-works projects that were paid for and never built. They read like a laundry list of what could’ve been, said Etzer Emile, a 33-year-old economist and author of the book, “Haiti Has Chosen to Become a Poor Country: The 20 Lessons That Prove It.”

“PetroCaribe is the biggest chance we missed in the last 30 years, in terms of opportunity to really do something for the country,” Emile said. “If this money was used properly, it could easily generate 5, 6, 7% [gross domestic product] growth for 10 years.”

After Friday’s protest, the Petrochallengers are looking to mid-May, when the audit court said it will finally release the final chapter of its report. It’s expected to implicate many more powerful people. That’s exactly why the Petrochallengers believe they must keep protesting: to ensure it won’t be buried.

Asked whether she considers herself a revolutionary, Douyon laughed.

“I’m afraid of the word,” she said. “It’s too big.”

“At least we are brave enough to say, ‘OK, we want to do something,’ and maybe after that they will call us revolutionary,” she said. “But for now, let’s say that we are citizens. We’re tired, and we are trying to do something.”

Tania Karas, Amy Bracken and Cristina Baussan reported from Port-au-Prince, Haiti.