A micro safari through household germs reveals that cleanliness isn’t always a good thing

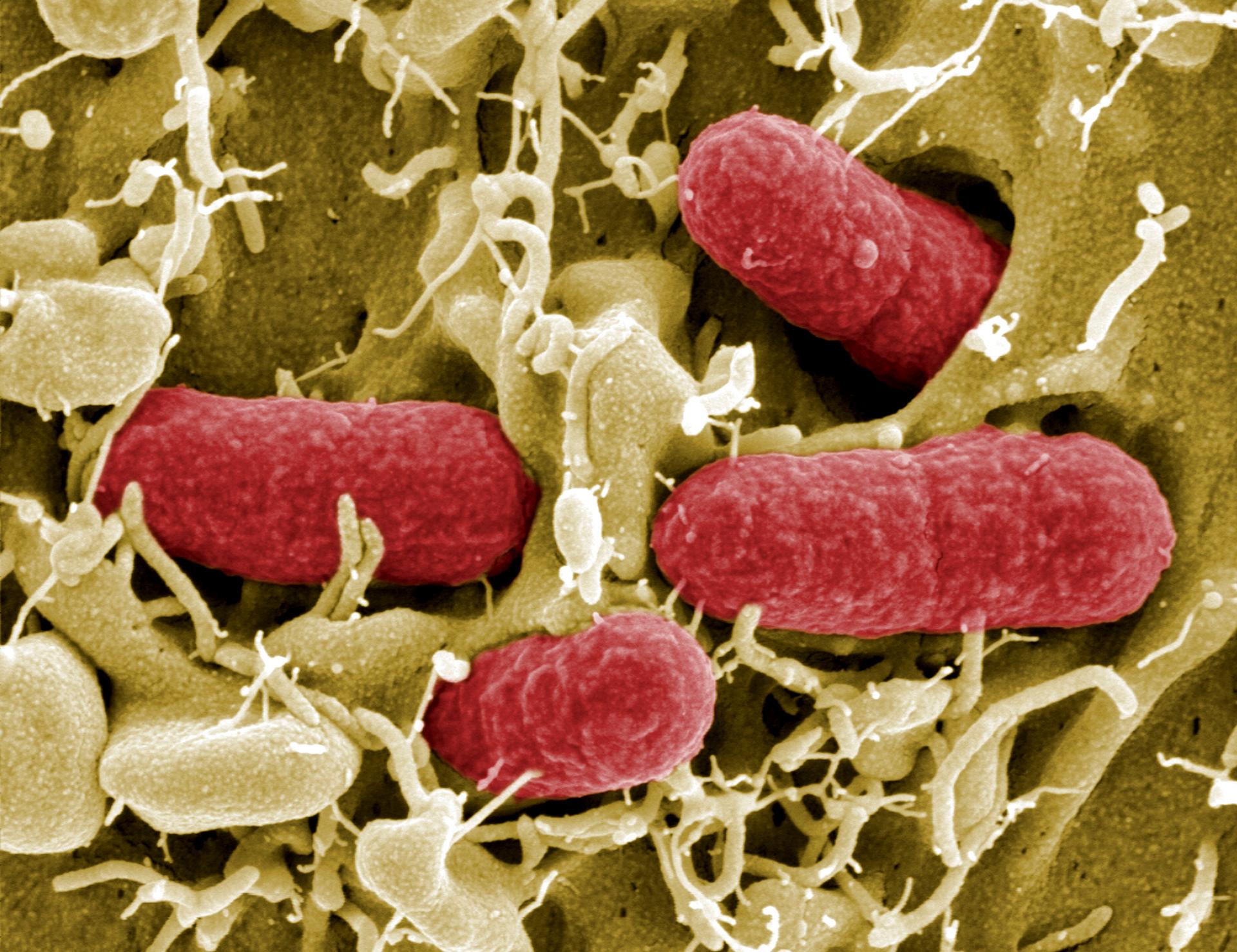

Bacteria shown in an electron microscope.

Queen Elizabeth I — who ruled England from 1558 to 1603 — one declared, “I bathe once a month whether I need it or not.” Without question, our perception of cleanliness has changed radically, but our modern-day obsession with hygiene may not be an unalloyed good.

Every imaginable surface around us is covered in bacteria, according to Rob Dunn, a professor of Applied Ecology at both North Carolina State and the Natural History Museum of Denmark. In his book, “Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honeybees, the Natural History of Where We Live,” Dunn explains that we are always surrounded by countless creatures that are naked to the human eye.

Related: Superbugs: India and the Rise of Drug-Resistant Germs

If you were to take a journey through your home with a microscope in hand, “It’d be like going off in a ship, like Darwin traveling the world, and every time you came around a corner, you’d come across something new,” according to Dunn.

Germ theory, which came into wide acceptance in the late 1800s, brought much greater awareness about health and hygiene and helped people understand how disease could be spread through touch, the sharing of water, etc. But over time, there has been an increased fervor about getting rid of bacteria, sometimes with unexpected consequences.

Lots of bacteria help us and enrich our lives, Dunn says. He explains that when we season our food with salt, the flavor comes from square-shaped bacteria that have been present in the salt crystal for hundreds of thousands of years. Lots of our yogurt is produced from the bacteria bulgaricus, which — if you can believe it — traces its roots to a man in Bulgaria.

Related: The future of agriculture may be too small to see. Think microbes

Dunn believes our obsession with cleanliness really began after World War II, when the language and sentiment of the battlefield moved into our homes. Pesticides and antimicrobials began to be used as weapons against the microscopic beings in our living spaces, and the need to control and sterilize our homes came to define our modern sense of hygiene. Companies were able to tap into consumers’ fears and sell products that promised to kill all forms of germs, both harmful and benign.

The problem, Dunn says, is that bacteria that harm us are only a tiny minority of the species around us. “When we try to kill everything, we are more likely to favor the harmful species,” he argues, “and that sets us up for all sorts of problems.”

The use of household products that claim to kill 99 percent of germs, is the “ideal recipe” for speeding up evolution, according to Dunn. He says we are creating an environment that’s counterproductive and actually promotes the evolution of the surviving 1 percent. Similarly, the overuse of antibiotics has led to the evolution of new resistant, species of bacteria.

Dunn believes it’s time to change the conversation, and imagine a different kind of future, one where germs and microbes are viewed a little less skeptically – and, more often, as assets to human health.

Nadia Lewis is an intern at Innovation Hub. A version of this story originally appeared on the Innovation Hub blog.