Blame game over aid leaves Syrian refugees stranded in desert ‘death’ camp

Many people living in Rukban — a remote, informal desert settlement in Syria — packed all their belongings into cars and left when the Syrian war reached their towns. Here, a woman washes a large carpet for her home.

Stranded in the remote deserts of Syria near the Jordanian border lies Rukban Camp — an unofficial tent city of over 40,000 displaced people who fled from war in Syria. What began as an informal settlement in 2014 evolved over time into a complex camp with no running water, regular food supplies or access to medical care.

“I can’t explain to you how bad the situation is,” Rukban resident Muhammad A’kil, 27, told The World over a smuggled satellite phone that connects to the internet for about one hour every few days. A’kil, originally from Homs, Syria, has been in limbo at the camp for four years.

“Don’t call it Rukban Camp; it’s a death camp.”

“Don’t call it Rukban Camp; it’s a death camp,” A’kil said.

At Rukban, babies die of cold, children of hunger, and adults from minor illnesses while waiting for Jordanian authorities to administer special passes for emergencies only. The situation was a disaster even years ago — and it’s only gotten worse since the diplomatic blame game over responsibility for reaching Rukban with essential aid has heightened.

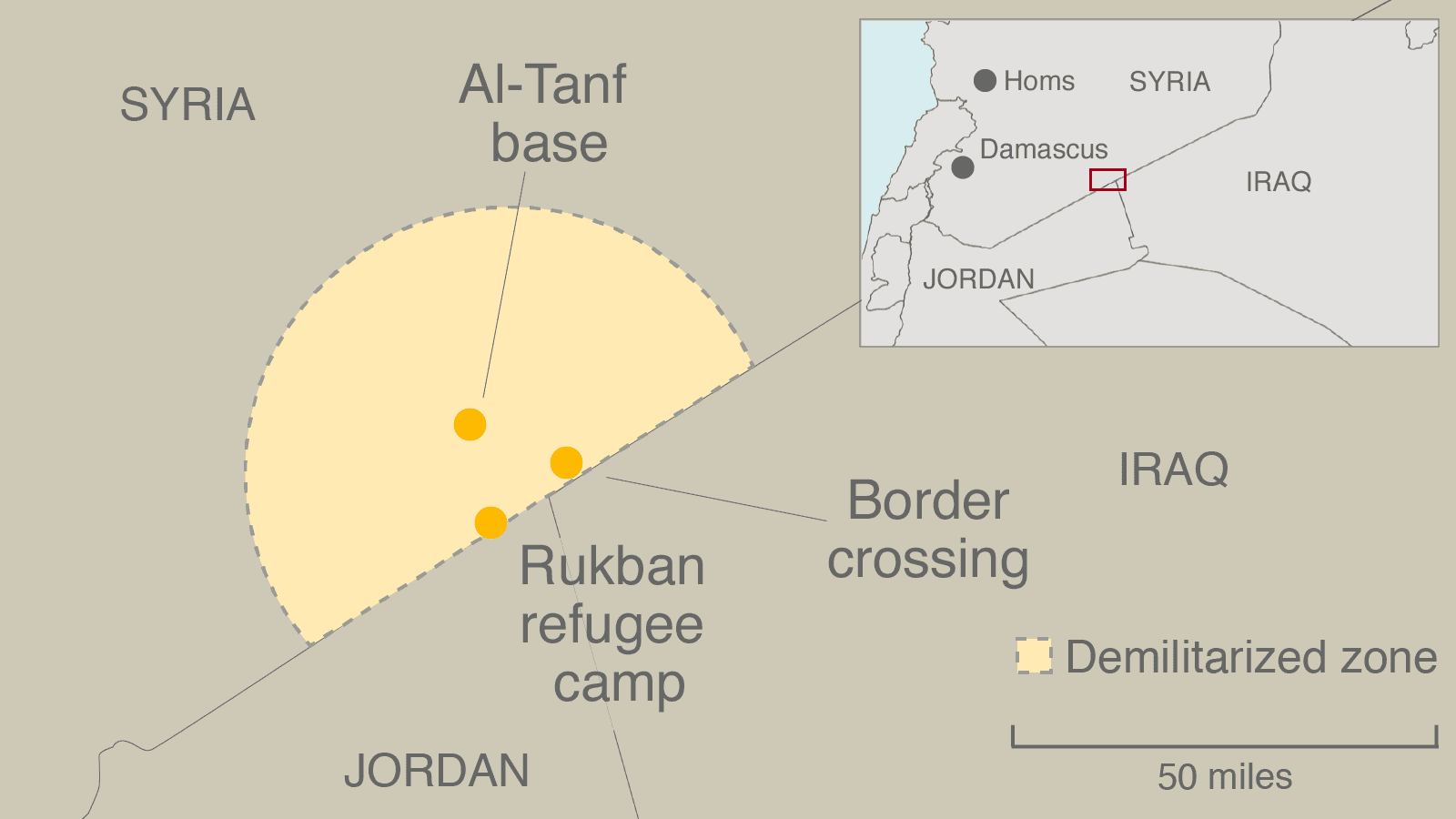

Just 15.5 miles up the road from Rukban is a US military base at al-Tanf, staffed with around 200 American soldiers and allied rebel fighters. And just across the border on the Jordanian side, United Nations aid trucks wait for the diplomatic signal to deliver the badly needed aid.

But the border gates — only two miles away from the first tent that forms Rukban — remains shut.

The aid blame game, explained

With hungry people on one side of the border, and trucks full of food on the other, it seems like an easy fix — but a complex web of negotiations between leaders of Syria, Russia, Jordan, Iran, the United States and the United Nations have stalled aid for months at a time.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Damascus is fully stocked and ready to deliver aid to Rukban, but it requires Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government to grant permission to send any aid convoys.

“Anytime we talk with the UN to get the food, they say, ‘There’s no shortage of food or medicine or any kind of support, but we need Damascus’ approval; without Damascus, we cannot move.'”

“Anytime we talk with the UN to get the food, they say, ‘There’s no shortage of food or medicine or any kind of support, but we need Damascus’ approval; without Damascus, we cannot move,'” said Bassam Barabandi, an adviser to the Syrian opposition High Negotiations Committee who worked as career diplomat for the Syrian government in Washington until 2013.

Related: As US declares victory over ISIS, a withdrawal from Syria proves perilous

“Jordan has made it clear that they will not allow anything to come from Jordan to Syria. Iraq did the same, so the only way to get the food or humanitarian aid is from the UN office in Damascus,” Barabandi said.

Jordan sealed the border after an ISIS-claimed suicide bomber struck the crossing in 2016.

The American military base at al-Tanf has an airstrip that could be used to fly in humanitarian aid, but they don’t use it, Barabandi said. “America says they don’t have any legal mandate to support these people, even if they are just a few miles away from them.”

Yet, when Syrian and Iranian forces have entered the 34-mile perimeter around the base, American warplanes have responded with strikes — effectively putting Rukban and its residents under American protection from Assad’s forces.

Al-Tanf was originally intended as a launchpad for fighting ISIS in southern Syria, and for the train-and-equip program for allied rebels, which ended in failure in 2015. As ISIS was beaten back from the area, al-Tanf’s mission has gradually evolved to include countering Iran, and de facto protecting the people of Rukban camp.

The dusty highway that passes through Rukban leads all the way from Tehran, Iran, to the Mediterranean Sea — and while attention is on the battle to retake ISIS’s last stronghold, US military officials still consider al-Tanf crucial to blocking Iranian oil- and weapons-supply lines from reaching Damascus.

Russia and the Syrian government charge that the American base at al-Tanf is blocking convoys from reaching Rukban. Assad and Russia have tolerated the base’s presence on Syrian soil as part of an agreement that the US would only attack ISIS — not support any rebel attacks on government forces. But with ISIS now down — yet still not defeated — the raison d’être for an American presence at al-Tanf fades — along with Assad’s patience.

“The US will remain at al-Tanf to continue the campaign against ISIS.”

In his first public address in over a year, Assad reiterated promises that his forces would recapture “every inch” of the country’s territory lost to ISIS, and to the rebel groups who now control the al-Tanf area with US support.

When US President Donald Trump made a surprise announcement in December promising “complete withdrawal” of American troops from Syria, Rukban residents panicked. Without US protection, there would be nothing standing in the way between them and Assad’s forces.

But US military commander Sean Robertson confirmed in an email that “The US will remain at al-Tanf to continue the campaign against ISIS,” declining further comment.

Related: When the US pulls out of Syria, what happens to ISIS?

“The US doesn’t want to be involved in any effort that looks like rebuilding,” said opposition negotiator Barabandi. “They don’t want to look like they are owning anything in Syria. But if the United States wanted to help, they would help.”

Rukban stands out as another bitter example of how delivering humanitarian aid can often get hampered by politics.

“When aid becomes a proxy for a political struggle, it’s just much, much harder to get it to the communities who need it, because one side or the other will see it as a threat.”

“When aid becomes a proxy for a political struggle, it’s just much, much harder to get it to the communities who need it, because one side or the other will see it as a threat,” said Jeremy Konyndyk, former director of foreign disaster assistance programs for USAID in Syria during the Obama administration.

Life inside — and beyond — Rukban

Fleeing the war, many Syrians packed up their belongings hoping to reach Jordan, which has taken in more than 630,000 Syrian refugees since 2011. But as more Syrians continued to flee, it put a strain on Jordan’s limited resources, and eventually, only a small number were granted refuge. The rest were turned away.

Rukban, as an improvised settlement, continued to grow, reaching up to 75,000 people at one point. People clustered according to their hometowns, essentially forming neighborhoods and Rukban evolved into a small city — but it still lacks basic infrastructure.

“Inside the settlement, you have a kind of downtown, and you can see that the people living there are trying to re-create the city life that they were part of before,” said Marwa Awad, the spokeswoman for the World Food Program. Some at Rukban have jobs while others have formed committees. There is even a football league for both children and adults.

The last aid convoy reached the camp in February 2019 after complex negotiations lasting four months between the Syrian regime and elected representatives from Rukban led to a deal. To deliver the aid, the UN needed Assad’s government in Damascus to agree to send the convoys and the Americans at al-Tanf had to agree to allow Syrian troops into its perimeter.

But for some, it was too late.

A’kil says his teenage cousin, gravely ill with pulmonary edema, waited in a line at the border crossing every day for two months to request permission to enter a Jordanian hospital. “The day we buried him, the permission came,” he said.

Aid workers say the aid that did arrive could barely cover residents’ needs through the middle of March.

When Awad went to visit Rukban along with the convoy in February, she said the conditions were worse than other places she visited in Syria.

“They had barbershops, they had restaurants, even a shawarma shop — where nobody was buying — even bread is eight times as expensive as it is in Damascus,” Awad said.

Even after they received the bare essentials of food and medicine, it’s a far cry from a long-term solution, Awad said.

“There is a risk of a lost generation there if these children don’t get out soon enough to be incorporated back into an educational system. There are schools, but they’re really the farthest from what you’d know as a school. … It’s a crisis.”

“There is a risk of a lost generation there if these children don’t get out soon enough to be incorporated back into an educational system. There are schools, but they’re really the farthest from what you’d know as a school,” Awad said. “It’s a crisis.”

According to UNOCHA internal data, the majority of Rukban residents — over 2,700 families — wish to return to their hometowns, which are now under the control of the Syrian government.

“But they also conveyed that they need assurances for their safety and protection both during any process of returning and in the future,” a UNOCHA official in Damascus said via email.

Related: Amnesty accuses Syria of ‘extermination’ of thousands of prisoners

Many Syrians fear imprisonment or being conscripted into the Syrian army after Damascus placed tens of thousands of men under the age of 46 on wanted lists for deserting a second tour of mandatory military service.

“The [Assad] regime is trying to force us by feigning a welcoming face,” A’kil said. “But God knows, it won’t be any welcome. They will kill us.”