Does Duterte’s wrath against the Catholic Church have no limit?

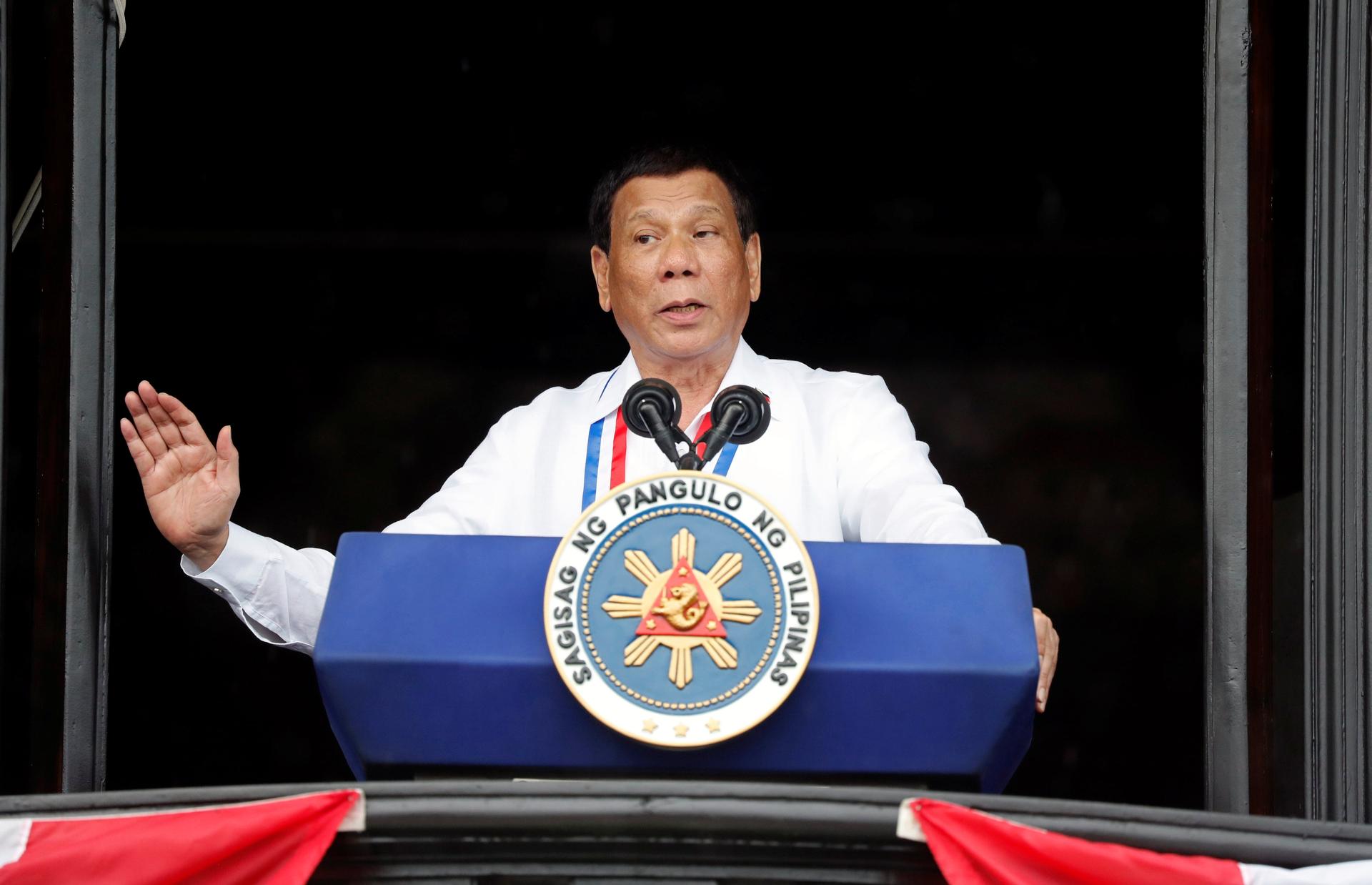

President Rodrigo Duterte speaks during the 120th Philippine Independence Day celebration at the Emilio Aguinaldo shrine in Kawit, Cavite, in the Philippines, June 12, 2018.

Rodrigo Duterte delights in shock value. He’s threatened to slap UN officials. He once told former US President Barack Obama to “go to hell.” As for his signature policy, a war on meth that has killed as many as 20,000 people, the Philippine president vows to “slaughter” drug users just as Adolph Hitler killed Jews.

But in recent months, Duterte has focused much of his wrath on Catholic holy men — a group that past presidents have courted and criticized gingerly, if at all.

Yet, Duterte calls them “sons of bitches” and talks openly about wanting to beat up bishops and priests. To another bishop who condemned his drug war, Duterte said he’d have the man beheaded.

Attacks on the church are now part of the Duterte doctrine, which contends that it is “the most hypocritical institution in the entire Philippines.”

Related: Inside the Philippines’ women-run crime ring selling abortion elixirs

Conventional wisdom says that threatening to fistfight priests is tantamount to political suicide in the Philippines, a nation where the people, government and culture are intertwined with Catholicism. The faith is followed by 8 in 10 Filipinos.

Yet, Duterte’s anti-Catholic scorn does not appear to be seriously damaging his appeal. The first polls of 2019 show the president’s approval rating is up to 80 percent.

How is he getting away with this?

“Duterte is just a completely unprecedented species,” says Richard Javad Heydarian, a Manila-based academic and author of “The Rise of Duterte,” a critical examination of the president. “The same kinds of rules that applied to his predecessors no longer apply to him. Because he has changed the game itself.”

There are several forces at play allowing Duterte to attack priests without incurring severe political damage.

Chief among them are the church’s moral crusades, which are increasingly out of sync with modern life. The institution has thrown its political might behind its own war on drugs, namely a campaign to rid the Philippines of contraception — both birth control pills and contraceptive, injectable drugs.

Related: A bill to allow divorce in the Philippines could mean freedom for some women in New York

This movement, bitterly fought in the courts and congress by church-aligned lawyers and politicians, is unpopular among most Filipinos. Nor is the church’s fight to keep divorce illegal. Duterte’s team argues instead that the church should stand down and respect Filipinas’ right to control their destiny.

“There’s a church-versus-state element that you have to look at,” Heydarian says. “It’s kind of a 21st-century version of Henry the VIII challenging the Catholic Church in Rome.”

Then there is the fact that, in the Philippines, practically everyone knows Duterte claims he was molested by an American priest — and has called out his abuser by name.

This seems to provide some cover for his more outrageous comments, in which he asserts that “most priests are homosexuals, almost 90 percent of you, so do not postulate on my morality.” (This go-to line about gay priests comes up in rants about men of the cloth preying on kids — thus callously conflating homosexuality with child sex abuse.)

Related: A new chapter, with the same old words, in the Catholic child abuse scandal

Duterte is also smitten with a book — “Altar of Secrets,” written by a now-deceased journalist named Aries C. Rufo — that exposes sex abuse within the Philippine Catholic Church.

He is so enamored by the book that he often urges crowds to read it during his speeches. Once, in the middle of a Russia Today interview, he ordered his staff to provide a personal copy to the interviewer.

But the book’s author probably wouldn’t enjoy seeing it used as a cudgel against the church, according to Rufo’s friend and colleague, Manuel Mogato, who won a Pulitzer Prize for covering Duterte’s drug war.

“That book was a breakthrough. It’s a well-researched look into the dark secrets of some bishops,” Mogato says. “But Aries was only trying to paint a picture of what the Philippine church actually is — that it contains people who are not morally upright. It’s not an attack on the whole institution.”

Duterte’s attack on Catholicism is a “bad strategy,” Mogato says, because “most Filipinos still have devotion to the church.” The president’s fury has increased as more influential bishops and priests condemn the drug war on moral terms.

“Duterte hates that. He hates any criticism,” Mogato says. “So, he just sees them as the opposition. He’s hoping people lose faith in the church so he can impose his policies freely upon the Filipinos.”

Related: How to rehabilitate addicts in the Philippines’ vicious drug war?

Many in the Philippines have deeply complex feelings towards the church. In recent decades, mass attendance has dwindled. Fewer than half of all Catholics now go each week. Yet, fewer than 1 percent have totally abandoned the institution.

Duterte has also drawn on the church’s bloody history to undermine its moral standing. As in the Americas, where Christopher Columbus converted Indigenous peoples through brutal means, Catholicism was also introduced to the Philippines at gunpoint.

Aligned with the Vatican, the Spanish empire was vicious in its 16th-century mission to conquer the various peoples inhabiting the Philippine isles. They were derided as inferior “heretics” by Spain’s King Philip II — for whom the islands are named after — even though the archipelago was home to well-organized societies running vast trade routes.

Duterte has suggested that, even today, a lingering sense that Filipinos are not equal to Europeans causes the world to pay scant attention to sexual “shenanigans” perpetrated by foreign priests against Filipinos.

(Such revelations are ongoing. As recently as December, an American priest in the Philippines was arrested for allegedly molesting dozens of boys.)

“There is no condemnation … is it because you don’t want to condemn your own countrymen?” Duterte said in a 2017 interview. “Or is it because the victims were just natives? Never mind about them. We were considered natives. And sometimes pictured as apes.”

There is a sense among some Catholics, Heydarian says, that Duterte is a “rude shock that’s necessary for the church to get its house in order.”

“Some people feel he’s gutsy,” he says. “That he’s saying things that even devout Catholics would love to say … Duterte has this gift of strongly anticipating what people want to hear, but can’t verbalize.”

“He’s essentially telling them, ‘Even if you may not agree, I’m the guy who pushes the boundaries.’ He’s like the ultimate free man, if you want to get philosophical … and he’s able to tap into the dark psyche of humanity.”

Related: Teen ‘widows’ of Duterte’s drug war face a bleak economic future

There is one red line, however, that Duterte has not crossed. He is not an atheist, he says, and remains adamant in his belief in an almighty power.

But not the higher power venerated by the Vatican.

“I never said I do not believe in God,” Duterte said in December. “What I said is your God is stupid. Mine has a lot of common sense. And that’s what I’ve told the bishops.”