How to rehabilitate addicts in the Philippines’ vicious drug war?

There are close to 1,100 patients at Manila's Bicutan Rehabilitation Center, double its maximum capacity.

Not far from the headquarters of the Philippine National Police in greater Manila, a tall concrete gate obscures the sight of a drug rehabilitation center called Bridges of Hope.

It’s safe and secluded, tucked away down a narrow residential side street overflowing with lush greenery. Inside, the center’s senior program director grimaces in frustration. It hasn’t been easy treating addiction since the start of the drug war.

“The reasons for the death of drug addicts have suddenly changed,” says Guillermo Gomez, the director. “It’s not death because of addiction. It’s death because of the environment. Even if you fix him and he gets well, he still might die.”

At least 7,000 suspected drug users and pushers have been killed by police or unidentified vigilantes since July. Some of the victims include those who have voluntarily surrendered to the authorities. Many fear that implicating yourself might actually put you more at risk.

This premonition has reverberated throughout the country’s rehab centers, where drug addicts have sought refuge in hopes of escaping a seemingly inevitable death on the streets. Confronting addiction is no longer the primary motive for drug dependents to enter into rehab, according to Gomez. It’s to guarantee safety.

“There’s a struggle when we have to explain to families that we’re not cold storage here,” Gomez says.

President Rodrigo Duterte has urged the killing of drug addicts “to save the next generation from perdition.” But human rights groups say the government fails to address the underlying factors behind the country’s widespread drug problem.

Street children regularly breathe in addictive inhalants like rugby to stave off hunger. Poor tricycle cab drivers sniff shabu — Filipino slang for methamphetamine — to stay awake throughout the night to be able to earn more money. For the breadwinners of impoverished families, there often seems to be no alternative.

“The problem with the drug war is the way the administration views the drug problem,” says Wilnor Papa, the local campaign coordinator for Amnesty International. “It’s very oversimplified without looking at the root causes.”

The Duterte administration characterizes its efforts, well, in a much more positive light.

“People are saying we support you, Mr. President, because for the first time you can walk in the streets without being bothered by a lot of criminals,” says John Castriciones, undersecretary of the department of the interior and local government.

He points to various community-based livelihood programs (including organic farming and livestock raising) and the expansion of residential rehab centers as evidence of the government’s comprehensive approach to addiction treatment.

“The community must look at [addicts] not as criminals, but as people who need help,” Castriciones says.

His appeal is a far cry from the president’s own words.

“Are they humans? What is your definition of a human being?” the president said last August.

Duterte has pushed for the reinstatement of capital punishment and called on Congress to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 9 years old. In reference to the construction of a new mega rehab center, located on the country’s largest military reservation, Duterte suggested the center “use high-wire fences so [the patients] get scared.”

Many rehab doctors find such rhetoric unhelpful.

“It actually distorts how the [drug] problem needs to be treated,” says Dondi Ayuyao, executive director of the New Beginnings Foundation in greater Manila. “A lot of the emphasis has been placed on apprehension and killing versus attention to treatment.”

Equating drug addicts with criminals has created a climate of fear among users. Perhaps that’s the goal.

Duterte’s iron-fisted approach has encouraged over a million alleged drug users and dealers to surrender. The influx of patients has overwhelmed government rehab centers and challenged doctors to address their patients’ newfound fears.

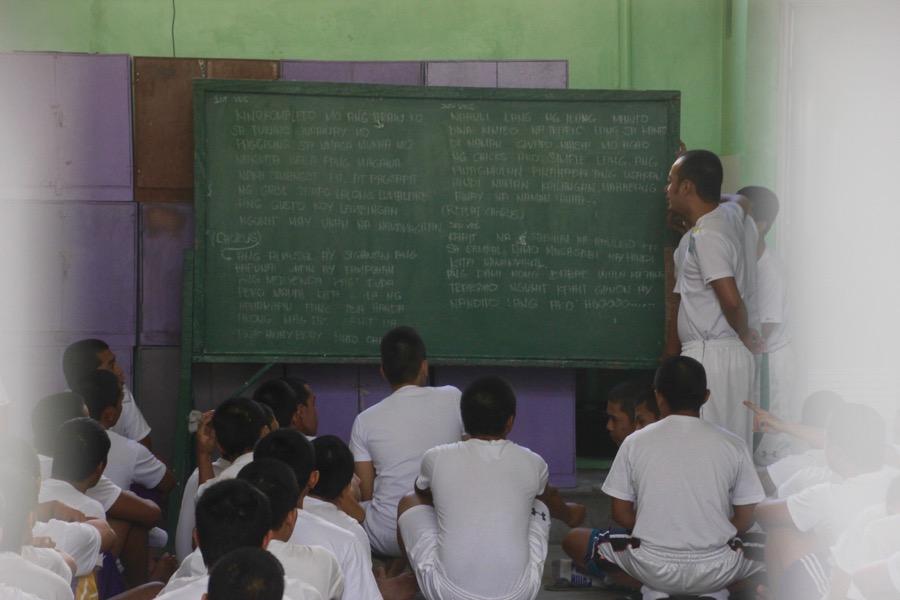

Occupancy at the Bicutan Rehabilitation Center, for example, has been stretched more than double its capacity of 550 beds. As a result, Dr. Bien Leabres has been forced to provide less one-on-one counseling and more group therapies and activities.

When patients vent their fears of reintegrating into society (a common occurrence), Leabres listens.

“We let it flow so they can have catharsis,” says Leabres, the chief medical doctor at Bicutan.

“The challenge for therapists now is to shift the thoughts of the patients from being fearful to motivating them to change,” he adds.

One of those patients is Ramon, 43, whose name has been changed to protect his identity. Ramon surrendered to the police in November after motorcycle-riding men killed one of his friends. At the behest of his concerned mother and wife, he decided to seek treatment. He’s safe now, but still worries about life after rehab.

“When I finish rehabilitation, I hope to get a certification from the PDEA [Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency] to clear my name from the watch list. But even if my name is cleared, I’m still not sure of my safety as long as Duterte is president,” says Ramon.

In 2002, the Philippine Congress overhauled the pre-existing drug treatment policy, taking a more clinical approach to addiction. The government, meanwhile, did little to clean up its rhetoric.

“We often see the police or even our legislators say that the menace of society is drugs and if we solve drugs then we solve everything,” says Lee Yarcia, a researcher at NoBox Transitions. “People like to subscribe to this narrative because it’s an easier solution, but it’s not evidence-based.”

NoBox is a rehab center that advocates harm reduction, a more therapeutic approach to addiction treatment. Its priority isn’t preventing abuse, but acknowledging that “the person using drugs is first and foremost a person,” says Inez Feria, the founder.

Although harm reduction is not yet universally accepted in the Philippines, a bill recently filed in the Senate looks to mainstream the approach.

Until then, drug users will continue to seek refuge in rehab centers. Doctors will continue treating a population consumed by fear and drug users will still be gunned down in the streets. After all, that’s what Duterte promised.