A Google affiliate is planning a ‘smart’ neighborhood in Toronto. Local opposition is growing.

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Sidewalk Labs CEO Dan Doctoroff, right, smile as they look at city models built by children before a press conference where Alphabet Inc., the owner of Google, announced the project “Sidewalk Toronto,” which will develop an area of Toronto’s waterfront using new technologies to develop high-tech urban areas in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, Oct. 17, 2017.

A little over a year ago, Daniel Doctoroff, Chairman and CEO of Sidewalk Labs, Google’s sister company, took the stage at a town-hall-style meeting in Toronto, Canada.

It was the first in a series of forums co-hosted by Sidewalk Labs to keep the Toronto community in the loop about what they wanted to create there: a neighborhood built from “the internet up.”

“We started with a thought experiment, basically,” Doctoroff told the crowd during that November 2017 meeting. “If you could create a city, or a district, or a neighborhood in the internet era, what would it be? We brought together experts from all over the world.”

And they became convinced, Doctoroff said, that they could “take truly visionary urban planning, mix it together with cutting-edge technology” and begin to alleviate some of the biggest headaches that come with living in a city: traffic, unaffordable housing, pollution and threats to public safety.

“We then decided that what we wanted to do was find the best place to partner to try and explore these ideas,” Doctoroff said. “And out of the entire world, the single place that we thought was the best was Toronto.”

In the deal, Sidewalk Labs got a unique opportunity to test out its ideas about data-rich living IRL — in real life — in Toronto.

Just a few months before, the Google affiliate had responded to a request for proposals put out by a Canadian agency looking for a partner to come up with a plan and funding for a 12-acre parcel of land on Toronto’s Eastern Waterfront. It won.

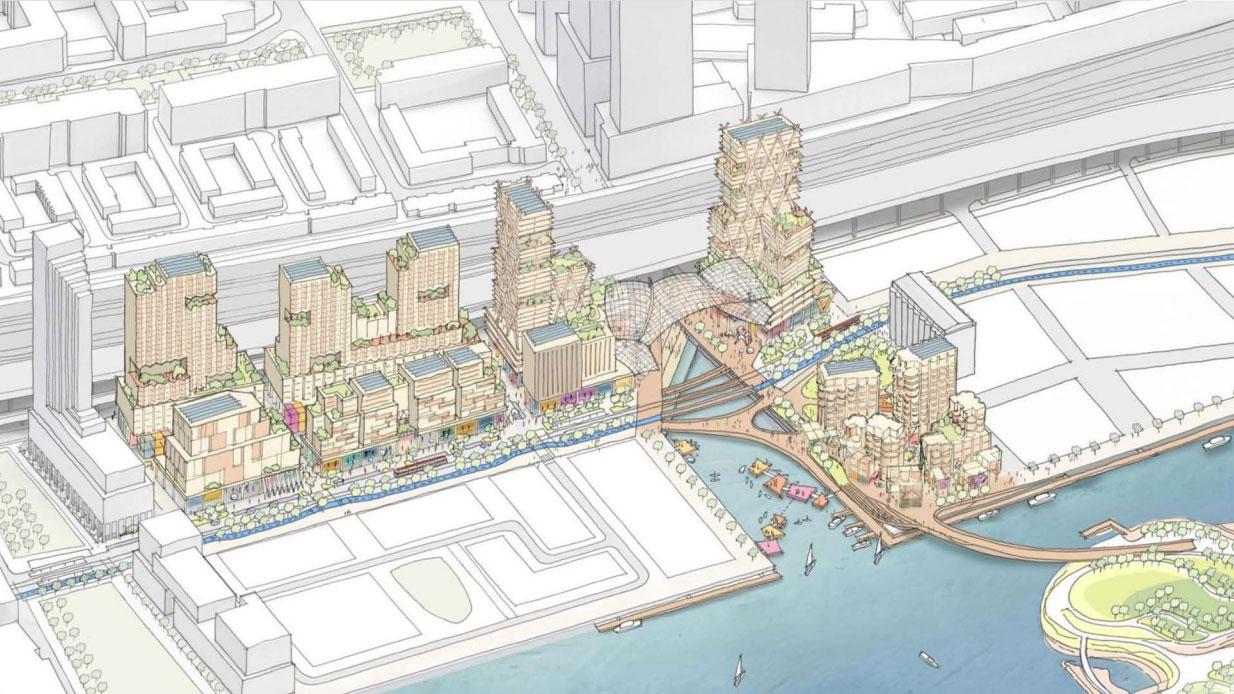

In its initial vision plan, released to the public in October 2017, Sidewalk Labs imagined a futuristic neighborhood “with connectivity designed into its very foundation.” It would have everything from self-driving shuttles to buildings created from sustainable materials to delivery robots and drones and adaptive traffic lights that would predict traffic patterns. It would be data-driven and that data would be used to improve almost every aspect of everyday life.

Related: Google workers around the world protest its corporate culture

That utopian urban dream sounded more like a nightmare to many in the Toronto area, including David Murakami Wood, an associate professor at Ontario’s Queen’s University, who researches smart cities, security, and surveillance.

“I do not think that tech corporations are the appropriate organizations to be managing our cities,” Murakami Wood said.

He recounts the period when Sidewalk Labs first arrived in Toronto with resentment: an American company with ties to Silicon Valley had parachuted in to disrupt a city that didn’t want to be disrupted.

“It felt like … being lectured by a load of New Yorkers about how Toronto could be better,” Murakami Wood said. “I think that put a lot of people’s backs up in Toronto.”

(Sidewalk Labs is headquartered in Manhattan, and Doctoroff spent seven years as deputy mayor of New York City starting in 2001.)

But what most bothers Murakami Wood and many others opposed to this project is how Sidewalk Labs ended up in Toronto.

The agency that chose Sidewalk Labs as its partner in this project is not a government agency. Waterfront Toronto is a public corporation, created by the governments of Toronto, Ontario, and Canada in the early 2000s. Its mandate is to develop an 800-acre expanse of land that sits on the edge of Lake Ontario. Sidewalk Labs won the bid to come up with plans for a small slice of that parcel.

“That is not the way things should be done. There should be a participatory process which comes from the bottom up, it should be dealt with through democratic processes,” Murakami Wood said.

Waterfront Toronto has repeatedly stood by its selection process. But criticism of it has been growing in recent weeks.

Related: This Google engineer was asked to create a censored version of Google News for China. He refused.

In a report released earlier this month, Ontario’s auditor general slammed Waterfront Toronto for its handling of the selection process, writing that the agency gave Sidewalk Labs access to more information than other bidders and that it entered into an agreement with the company “without sufficient due diligence and provincial involvement.”

The project is also raising a lot of concerns about data collection and privacy.

“We are in no way ready to manage this type of project where it’s being discussed as a smart neighborhood where there’s gonna be sensors and data collection everywhere,” said Bianca Wylie, a Toronto resident and the founder of the advocacy group Tech Reset Canada. “We never talked about having a smart city. We never talked about being the test bed for a company that’s a Google affiliate.”

Wylie and others involved with Tech Reset Canada have been holding a series of discussions around what this project would mean for Toronto.

In the wake of intense backlash since releasing its first plan last year, Sidewalk Labs has tried to walk back some of the features that would make this smart neighborhood, well, smart. But there are still a lot of questions about how the data of those who live and work in the neighborhood — as well as those who visit — would be collected and used.

Related: EU launches new data privacy rules amid enforcement uncertainty

Several people have distanced themselves from the project or outright quit over these concerns.

Ann Cavoukian, Ontario’s former privacy commissioner who now heads the Privacy by Design Centre of Excellence at Ontario’s Ryerson University, is one of them. Cavoukian was approached early on to become a consultant on this project.

“I was delighted because I wanted it to be a smart city of privacy, not a smart city of surveillance,” she said.

Cavoukian is not against data collection. But she worried that in this smart city environment, there would be no real opportunity for people to opt out of having their data collected.

“You would know … who’s going where … license plate numbers, individuals going from point A to [point] B at what times of day. It would be unthinkable,” she said. “So because of that, I said all the data collected from sensors and other technologies must be de-identified or anonymized at source — meaning, the minute it’s collected, you have to scrub it for all personal identifiers, and then you can use the data but it won’t be about any identifiable individuals, it’ll just be generic data.”

Sidewalk Labs agreed to de-identify all data collected. But the company told Cavoukian it couldn’t guarantee everyone else involved in the project would do the same.

“And the minute I heard that I knew I had to resign,” Cavoukian said. “I had to do it because I had to make a statement that this was not acceptable.”

Sidewalk Labs is expected to release its final master plan for the neighborhood in the spring of 2019. Some critics in Toronto say there’s nothing that can be done to change their minds and that they want to see the project scrapped altogether.

Related: The new DHS plan to gather social media information has privacy advocates up in arms

“We see absolutely no reason to push the reset button and restart this process,” said Kristina Verner, vice president of innovation, sustainability, and prosperity for Waterfront Toronto.

Verner says she wishes critics understood one thing: This is not a done deal.

It may turn out that Waterfront Toronto decides not to move forward with Sidewalk Lab’s plan for the neighborhood.

Regardless of what happens, though, the experience in Toronto shows just how tricky it can be to bring a smart city online.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!