Ice is us: Alaska Natives face the demise of the Arctic ice pack

Bowhead whale bones form an arch on the beach near in the Iñupiaq community of Utqiagvik, Alaska, once known as Barrow. Whales have been a crucial food source along the harsh and isolated Arctic coast for millenia.

This story comes to us through a partnership with the podcast and radio program Threshold, with funding support from the Pulitzer Center.

David Leavitt has spent a lifetime watching ice, and how it’s changing.

“Long time ago … good ice all the time,” he said.

Leavitt is 88 and lives in Utqiagvik, Alaska, once known as Barrow, the northernmost city in the US, on the shore of the Arctic Ocean.

Leavitt grew up in the region, hunting with his family and living the seminomadic life that for thousands of years was the hallmark of his Iñupiat people, one of the Indigenous groups of the North American Arctic.

Sea ice is a big part that life. At least, it used to be.

“Really, not good ice anymore,” Leavitt said, straining to find the right English words to describe the change he’s seen. “Yeah, ice isn’t ah, you know, it’s not good anymore.”

Related: The Arctic’s Sámi people push for a sustainable Norway

When he was a child, Leavitt says, the ocean would freeze in October. But now, sometimes it’s not even frozen in December. The ice also lasted longer back then. He says it often wouldn’t melt until July.

“Come up here for the Fourth of July with a dog team,” Leavitt said, recalling the days when he would take a dogsled to summer celebrations on the ice.

His eyes lit up as remembered the scene.

But, he repeated, “Not anymore. You know, you know, that ice is not good anymore.”

It’s not good anymore because the Earth is warming up fast, and it’s warming fastest in the Arctic. The Native communities of northern Alaska have been watching that happen for decades.

“It was a gradual change and then it accelerated,” said Gordon Brower, who also lives in Utqiagvik.

Related: Arctic permafrost is starting to thaw. Here’s why we should all care.

Like Leavitt, Brower remembers when it was normal for the sea ice here to stick around well into the summer and build up from year to year.

“In the ’70s, you had multiyear ice, all the way up to the 1980s,” he said. “And to me, that’s a vivid memory, because that’s when I was very active as a young person.

“And then from the ’80s to the ’90s, another era of change in the ice. And then from the ’90s to today, a much more accelerated pace, because the retreat is so extensive. You would see probably retreats in the ’70s [of] maybe 15, 20 miles. But today, you’re looking at a retreat of ice for hundreds of miles.”

Brower remembers this so clearly because he spent a lot of time living on the ice, learning how to hunt whales, something that he knows many other Americans don’t look kindly on.

“I know it’s not a very big thing to talk about down states,” he said, referring to the Lower 48, “about catching whales and killing them. But we have been doing that for thousands of years to survive. That’s the only way we could have survived here.”

Related: An Alaskan village is falling into the sea. Washington is looking the other way.

Whales have always been a crucial food source along the harsh and isolated Arctic coast. Even today, food that’s shipped into grocery stores here can be wildly expensive, so the ability to hunt whales really matters. That’s why Indigenous communities in Utqiagvik and across the Arctic fought hard for the right to keep their subsistence hunt when most commercial whaling was banned a few decades ago.

Brower says people here use every part of the whale, and they share the food throughout the community. To be part of a crew providing this food was — and still is — a major source of pride.

“The whale brings on a festival of its own,” Brower said. “Everybody gets new garments and clothing, and sometimes people get married and other things happen.

“It feels good because a whale means so much. Because there’s the widows; there’s the ill; there’s the children; there’s the ability to make food manageable for a large community. It makes me feel good that I’m doing a service for my community.”

The whales hunted here are mostly bowheads, which can grow up to 60 feet long and weigh 100 tons. Brower learned how to hunt whales as a child, and he says a big part of that education involved learning about sea ice.

“Our camps were sometimes 15 miles out” on the ice, he said. “We would live offshore for up to a month trying to harvest these marine mammals.”

Related: In Iceland, a shifting sculpture for a changing Arctic

The hunting parties would bring food and shelter but they didn’t need to bring fresh water because they could get that from the ice itself. This is one of the things Brower learned — as sea ice gets older, it squeezes the salt out. So, if you have ice that’s five or 10 years old, you can melt it and drink it.

But, he said, “You don’t see that anymore. And now, you’re going to bring your own water from shore to your camp offshore, because you’re not seeing these glaciated-type ice that develops over long periods of time that are salt-free.”

And that’s not the only change out on the ice.

“It’s considerably, I think, more dangerous,” Brower said. “You’re not as sure-footed on the ice anymore.”

In many communities up here, more people are falling through the ice now when they’re whaling or traveling, especially on snowmobiles. Loss of sea ice affects all kinds of animals, too — the polar bears that we hear so much about, but also narwhals, walruses, seals, even birds. They’re all being affected as the sea ice recedes.

And people much farther away are watching.

“The health of the ice cover is not very good,” said Mark Serreze, the director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

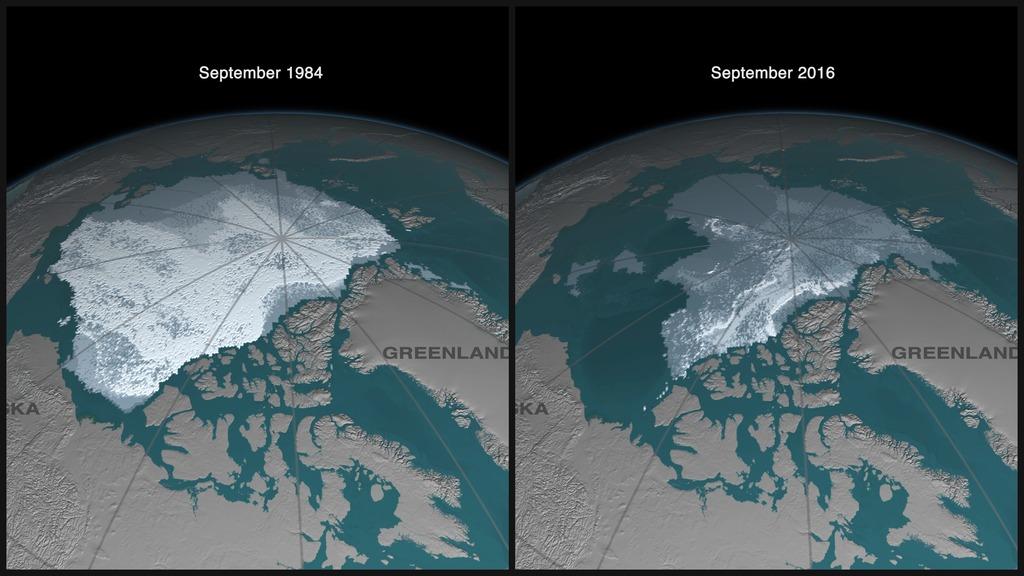

“Since the dawn of this, of the modern satellite record [in] 1979, it’s [been] decreasing in all months,” Serreze said. “In September, especially. September is the end of the melt season in the Arctic, and that’s when the biggest trends have been occurring. Something like 13 percent per decade. It’s tremendous.”

Sea ice grows in the winter, when the Arctic is very cold and dark, and then dies back every summer, when the region gets pounded by nonstop sunlight. But for all of human history, there’s always been some Arctic sea ice that doesn’t melt in the summer — the thick, multiyear ice that Gordon Brower talked about.

And like Brower, Serreze says there’s much less of it now.

“It’s getting so warm now that it’s hard to form all this really old, thick, multiyear ice, and some of [it] just melts away,” Serreze said. “But we really can’t regenerate it anymore.”

That means sea ice in the Arctic is getting thinner while also covering a smaller area. And that is a very big deal because one of the most important things polar ice does for everyone on Earth is reflect sunlight and heat back into space.

Scientists call it “albedo” — how reflective something is. And Serreze says sea ice in the Arctic is “one of the of the higher albedo surfaces of our planet” —a giant, reflective shield, bouncing heat away from us.

This is one of the reasons why the Arctic is warming up so fast.

But it’s not the end of the story of what’s changing as Arctic sea ice disappears.

The temperature difference between the cold Arctic and the warmer temperate zones is what drives the northern jet stream, the huge river of wind that flows around the northern hemisphere. As the Arctic warms and the temperature difference diminishes, some scientists think the jet stream may be getting out of whack, sometimes sending Arctic blasts south and heat waves north.

There’s still a lot to learn about all of these processes and other impacts of sea ice loss, but there’s one bottom line: Arctic sea ice has helped keep the Earth’s climate running in a more or less predictable way for thousands of years, and as humans warm up the planet, we’re making it harder for the ice to do that for us.

Which is why when Sheila Watt-Cloutier talks about Arctic people, she could be talking about all of us.

“Our lives depend on the ice, the cold and the snow,” said Watt-Cloutier, the former head of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, which advocates for the many different Inuit groups across the north.

It’s just that the people who live in the Arctic see and experience it far more directly than the rest of us. And that means much of the knowledge that people in the region have long relied on doesn’t serve the current generation here.

“Many of our elders are saying, ‘We are teaching you the traditional knowledge that we have been taught over millennia about safety, about the conditions of what is out there on that ice and snow,’” Watt-Cloutier said. “But they say there is a disclaimer now as a result of climate change, where many of our elders have said, ‘This is what I’m teaching you … however’ — and that’s the disclaimer here — “the rules are changing.””

Watt-Cloutier is from eastern Canada, thousands of miles from Utqiagvik, but she says the changes in the Arctic affect all of the 150,000 Inuit people who live here, in eastern Russia, Alaska, Canada and Greenland.

“It isn’t just the ice and the polar bear that we would be losing, but all of the wisdom [that] would go with that ice, as well. And that’s the fear that we have,” she said. “Our culture is so connected to everything that is around us, including the ice. And the ice, of course, is our life force. And as that starts to go, it minimizes our ability to live as Inuit as we’ve known it for millennia.”

That deep and tight connection was on display during a recent performance of traditional Iñupiaq dancing and drumming in Utqiagvik. The performers’ movements were all about hunting — they mimicked the paddling of the skin boats on the waves, and the careful leaps from one ice floe to another.

And they evoked the tight bond in this hunting culture between the human hunters and the animals, including the whales.

But even as they still need whales and have continued their subsistence hunting, people in Utqiagvik have also become part of the global cash economy. These days, they need textbooks, computers and hospital equipment. And in this part of Alaska, a lot of that cash comes from just one source.

“The Arctic is an oil and gas province,” said Gordon Brower. “We don’t have any other horse to ride up here.”

Fifty years ago, one of the largest oil fields in North America was discovered east of Utqiagvik, in Prudhoe Bay. Brower says local people knew then that it would mean big changes in their community, so they worked to forge agreements that would help preserve their culture while using the income from fossil fuel development to fund schools, hospitals, roads and more.

“We needed to do something so we were not completely overtaken and assimilated but to find a way to balance and coexist,” Brower said.

Since then, natural gas and coal have also been found in the region. The money earned from taking all of those fossil fuels out of the ground has transformed life up here, but it’s come at a cost, because those are the same things that, fed into the global economy, are causing the climate to warm up and the ice to melt away.

It’s an irony that’s not lost on people here.

“If you’re thinking about, am I contradicting myself in trying to balance oil and gas development with what’s going on today with the ice extent retreat, the [thawing] permafrost,” Brower said. “I don’t know. But I know we’re going to adapt, and we’ve still got to preserve the whale and do our best” to feed people.

Utqiagvik’s dilemma is the dilemma we’re all facing. We’re all drinking from the same oil well, even as it slowly disrupts everything around us. Oil, gas and coal are woven into the fabric of our entire lives, but the pollution from those fuels threatens all of us.

Some of the damage from that pollution is already baked in, but we know enough to be able to limit it — around the globe, and here in the Arctic. The first step, Mark Serreze says, is facing facts.

“We understand the basic science here,” Serreze said, adding, “We have got this nailed down. Climate change is real, and it is us.”

Amy Martin is the executive producer of the podcast and radio program Threshold.

Threshold producer Nick Mott contributed to this story.