An Alaskan village is falling into the sea. Washington is looking the other way.

This story comes to us through a partnership with the podcast and radio program Threshold, with funding support from the Pulitzer Center.

The sun never really sets on summer nights in the far north, and the endless twilight makes Shishmaref, Alaska, something of a kids’ paradise.

“There’s a lot of kids,” says 8-year-old Walter Nayokpuk, emerging from a swirling kid mosh pit in a wide spot of sand between some houses. “And we can be free!”

Related: In Iceland, a shifting sculpture for a changing Arctic

Free to roam in this Iñupiat village of about 600 people on a barrier island near the Bering Strait, just shy of the Arctic Circle.

There’s a church, a school, two stores and around 150 houses. For kids, it is a very safe place to play, and grow up.

But the paradox of Shishmaref is that it might be both one of the safest and one of the most dangerous places to live in America today: This small community is ground zero for climate change in the Arctic.

Shishmaref is the only town on Sarichef Island. And everywhere you go, you can see the waves and hear the constant roar of the ocean. The island is only about a quarter of a mile wide and it’s getting smaller.

“It’s changed a lot,” says Kate Kokeok, who grew up in Shishmaref and now teaches kindergarten here.

In decades past, Kokeok says, the sea ice around the island served as a kind of buffer, protecting it from the wind and waves when winter storms blew in.

But these days the ice is forming later and later.

“It was always frozen at the end of October,” Kokeok says. “It no longer is.”

That means the fierce winter waves that used to break on the ice far away from shore now slam directly into the island. At the same time, the permafrost beneath the town is thawing as temperatures rise, weakening its foundation.

The combined effect is a quickly receding coastline.

And that’s left Kokeok with a lot of memories of places that are now under water.

“Like, where the seawall is now, that’s where we used to have our playground,” she says. “Down that way, that’s where like 10 to 15 houses were. And, like, the last house that’s there now? There was a house next to it, a road, and then another house … You can see how much land was lost there.”

A lot of that land was lost in a storm in 1997, and then another in 2005. People gathered in the windy darkness to get the residents out and save as many of their belongings as possible.

After that 2005 storm the US Army Corps of Engineers built a new, stronger seawall. Kokeok says that probably saved even more houses.

But the seawall is just a temporary fix. Without the barrier of the ice, eventually, the ocean is going to wash this island away.

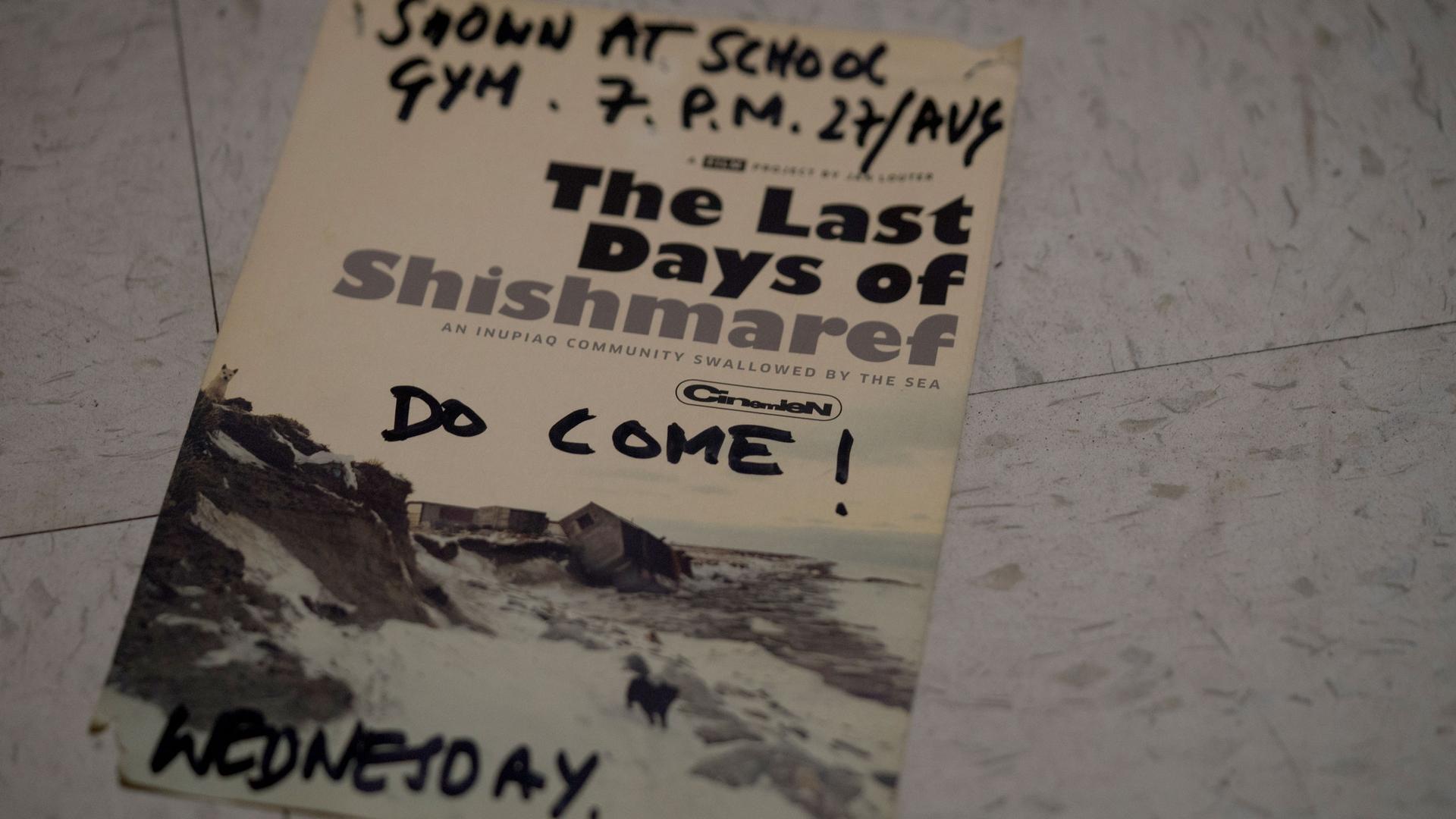

The people of Shishmaref know they’re not safe here, and two years ago, they voted to move the village to the mainland. In fact, the community has voted to relocate three times — in 2016, in 2002 and way back in 1973. People in Shishmaref were worried about erosion even then, although, at the time, no one knew how much climate change would accelerate the process.

They do now. According to a study conducted by a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, tiny Sarichef Island lost an average of seven and a half feet of land a year to erosion between 2003 and 2014.

And as the island shrinks and the sea ice recedes, the risks steadily rise. When major storms blow in, residents have nowhere to run. Shishmaref is not connected to any roads, and in a raging storm planes or boats would have a very hard time getting here.

Of course, climate change is only adding to a problem that already existed in Shishmaref — it was always vulnerable to erosion, making it a risky place for a permanent settlement.

So why was it there to begin with?

It’s a question Kelly Eningowuk, who heads the Anchorage-based Inuit Circumpolar Council in Alaska, hears a lot.

“I’ve heard something to the effect of, ‘These dumb Eskimos, why did they build their community on a barrier island?’” Eningowuk says. “The fact of the matter is, because [that’s where] the church and the Bureau of Indian Affairs school was built.”

Eningowuk grew up in Shishmaref and says until a hundred years or so ago there was no permanent village on Sarichef Island. Her ancestors lived all along this part of the coast, and while they used the island frequently, they didn’t live there year-round.

“They were kind of semi-nomadic. We didn’t have permanent settlements.”

But all of that changed in the early 1900s when the US government and the Lutheran church came to coastal Alaska and built churches and schools. It was an extension of the colonization process that had already swept through the lower 48 states. Alaska Native people were told they had to send their kids to the new schools or risk having them taken away.

So over time, the population of this part of the coast concentrated on Sarichef, and the process of “development” committed them to a spot that turned out to be very dangerous.

“They don’t have any way to get out of harm’s way right now,” says Joel Clement, a scientist and policy analyst who used to work at the US Department of the Interior. “So they’re in a tough spot in the fall with the storm season — and the storm season is expanding. That’s the top-level thing I worry about.”

Clement was one of the people leading the federal government’s effort to help Shishmaref and other coastal Alaskan communities under the Obama administration. When he was hired in 2010, the federal government had already issued two reports — in 2003 and 2009 — describing the threat in no uncertain terms.

The reports said more than 30 villages, including Shishmaref, were in “imminent danger.”

The worst-case scenario, Clement says, is that “a storm comes in and forces them off that land this year.”

At the Department of the Interior, Clement set out to get federal agencies to help protect people in coastal Alaska from the threats of rapid climate change. Shishmaref and other towns were already engaged in planning their own solutions, but the sticking point was money — moving a whole town is a complicated and expensive affair. One federal study pegged the cost of moving Shishmaref at $179 million.

Shishmaref doesn’t have that kind of money. They barely have any kind of money. Forty percent of people here live below the poverty line and many homes don’t even have running water.

But Congress was not supportive of helping with the move. Many members weren’t — and still aren’t — willing to accept that human-caused climate change is even real.

So, Clement says, “finding dollars was very difficult.”

Then in 2016, President Obama signed an executive order protecting marine resources in the Bering Sea and setting up a new structure for helping Arctic communities respond to climate change.

Clement was optimistic that the move would finally bring meaningful action for Shishmaref. While it came just before Obama left office, Clement was confident it would stand under the new Trump administration.

“Despite all the anti-climate change rhetoric out of these new folks, I wasn’t worried about climate change adaptation [efforts],” Clement says, because they were addressing very visible issues. “People are being directly impacted by climate change. It’s not a model, it’s not a theory, it’s fact. And, of course, I was being very naive.”

But less than four months into the new administration, President Trump revoked Obama’s executive order. The project was dead.

Clement was shocked.

“It was a clear shot across the bow,” he says, “that, hey, it doesn’t matter whether you are working on reducing greenhouse gas emissions or protecting people in peril. Anything that has a whiff of climate change to it has to stop.”

A few months later, Clement got reassigned to a totally unrelated job for which he had no qualifications. And he wasn’t alone. He found out that dozens more senior Interior Department executives had been reassigned.

“I realized … I was part of a purge,” he says.

Clement found a lawyer and filed a whistleblower complaint, which is still pending. He also wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post and started speaking publicly about what’s at stake — not just his and his colleagues’ jobs, but the people of many coastal Alaskan communities.

“Government should be scrambling to try and find ways to get people out of harm’s way,” he says. “It’s what government does.”

And Clement says the crisis facing Shishmaref and other Alaskan villages is just a hint of what’s to come.

If the federal government effectively tells these communities they’re on their own, he says, “they’ll be saying the same thing to Miami pretty soon … What happens up there in the face of climate change is an important bellwether for what’s going to happen in the rest of the coastal areas of the United States.”

“We are all American citizens,” he says, “and we have some expectation that we’re not on our own … That’s one of the things that makes this country great.”

The Interior Department did not respond to two separate requests for comment.

Clement says at least one coastal Alaskan village is likely to be wiped out within the next 10 years. It could be Shishmaref, and it doesn’t take much imagination at all to picture it — the winds wailing, the waves rising, and the frigid water rolling and crashing over the island on a dark winter night.

It’s a nightmare scenario. And it’s completely possible.

So in the absence of federal help, why don’t people just leave on their own? If not as a whole village, then at least as individuals and families?

Clement says that would amount to the “cultural death” of these communities.

“Each one of these villages is its own distinct culture, [they have] their own distinct dialect,” he says. “To ask them to just assimilate into another village somewhere is to ask them to let go of their culture entirely, which I think is just a horrible thought.”

It’s hard to find anyone in Shishmaref who disagrees with this. People here want to stay together.

“Lot of us like to take care of our community first and then ourselves last, you know?” says Shishmaref Vice Mayor Stanley Tocktoo.

People here rely on each other for all of the essentials of life. They visit each other when they’re sick, they take care of each other’s kids. They depend on subsistence hunting to feed their families and share that food with elders and others who can’t go out and hunt themselves. And they know that their future depends on keeping those relationships intact.

“[That’s] just the way our community is, you know?” Tocktoo says. “It comes from family ties, I guess. This community’s like a real big family.”

Tocktoo is on the search and rescue team here and knows better than anyone just how bad things could soon get. He is frustrated by the indifference in Washington.

“We’re Americans too, you know,” he says. “We don’t have to be treated like a third world country.”

And, he adds, “I can’t believe our president don’t believe in climate change.”

But the story of Shishmaref is more than just a story about the impacts and inequities of climate change. It’s a case study on how climate change can’t be understood in isolation from history and politics.

The community is here in large part because outsiders wanted to exert control over Indigenous Alaskans and their way of life. The US government was very effective when it wanted to make people settle in this particular place, but now that it’s clear they need to relocate, it’s so far proven completely ineffective in helping them to get out.

One of the climate change buzzwords right now is resilience. That’s something the people of Shishmaref are already experts in — they’ve been practicing it for a long, long time. What they’re asking for is basically the right to keep their community together so they can continue to practice resilience.

They just call it by a different name. Taking care of each other.

Amy Martin is the executive producer of the podcast and radio program Threshold.