Tommie Smith and John Carlos of the US raise their fists in a “Black Power Salute” during the playing of the national anthem at the Olympics in Mexico City, Mexico, 1968.

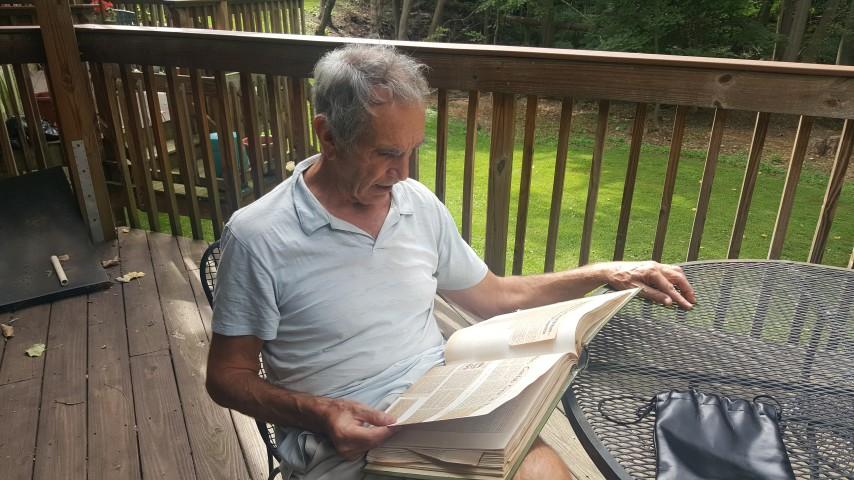

Andrew Larkin’s home in Northampton, Massachusetts is a memorial to his glory days of rowing for Harvard.

Two massive oars, inscribed with accomplishments like winning times against Yale and appearances in international races, hang over the door to his porch. His walls are adorned with black and white photos of young men sporting the Crimson’s signature H on their chests.

Larkin pulls out a record from 1968, the most important year in his athletic career: a scrapbook filled with news clippings.

That year, Larkin and his Harvard teammates represented the United States at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City. There, American runners John Carlos and Tommie Smith turned the world on its head by raising two fists in the air while the national anthem played. The black athletes later said they were protesting racial and economic inequalities.

Ten days before the opening ceremony, police and military troops in Mexico City opened fire on thousands of unarmed student protesters, killing hundreds.

For Larkin and the Harvard crew, it was hard to stay focused just on college and rowing because there was so much turmoil in this country, with protests against the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, and the massive confrontation outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

“It was a time where you had to get involved. Or at least I felt that, or we felt that,” Larkin said. “It’s a little silly to be playing around in boats when the whole world is going to hell.”

Heading into the Olympics, there was talk of black athletes sitting out of the games to protest racism.

The Harvard Crew, who were all white, wanted to help, so they drafted a letter that stated their support for their black teammates.

“We figured we could write letters,” Larkin said. “That was it. We didn’t have any idea that we were gonna do anything more audacious.”

But not every member of the crew signed on to the letter. And the boycott? It never came to pass.

Leon Coleman, a hurdler for the ’68 team from Boston, Massachusetts who finished fourth in his race, said there was a lot at stake.

“I had ran in the snow. I had ran in Franklin Park in the cold in the morning,” he said. “And then somebody tells you to boycott … You know, a lot of people gave up a lot of stuff for those events.”

Many athletes also feared repercussions back home if they demonstrated, he said. Coleman returned to historically black Winston-Salem State University in North Carolina and became a track coach.

Coleman, who now lives in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, was in the Mexico City stadium when Smith and Carlos came in first and third in the 200-meter final.

When the “Star Spangled Banner” came on over the stadium’s speakers during the medal awarding ceremony, Smith and Carlos each raised a single, black-gloved fist in silence.

“All of a sudden we saw some black gloves and we saw some fists go up,” Coleman said. “It was a shock for everybody. People really was amazed about it.”

The repercussions were immediate.

Smith and Carlos were both expelled from the Olympic Village and faced death threats upon returning home. Neither ran in the Olympics ever again.

But they weren’t the only ones who faced blowback.

The president of the US Olympic Committee, Douglas Roby, sent a letter to Harvard’s crew coach expressing his displeasure with the team’s actions.

Larkin read an excerpt: “Serious intellectual degeneration has taken place in this once great university, if you and several members of your crew are examples of the types of men that are within its walls.”

“This is hate mail with a letterhead,” Larkin remarked.

Coleman said he and other black Olympic athletes had trouble finding jobs when they got back home.

Nor did being an Olympian protect him from bigotry. Coleman was run out of South Boston simply because he and a friend went for a bike ride.

“The idea of you getting off a plane, and they’re calling you unacceptable names, using the N-word, and you saying, ‘Man, I damn near gave my life to get on this Olympic team,'” he said. “‘And you’re treating me like this? I mean, what the hell is going on?'”

Today, the torch that Smith and Carlos lit is still carried by athletes like Colin Kaepernick, who kneeled during the national anthem of National Football League games to protest police brutality.

Other athletes, like the Patriots’ Devin McCourty, have advocated directly for criminal justice reform.

Amira Rose Davis, a professor of history and women’s gender and sexuality studies at Penn State and a host of the feminist sports podcast “Burn It All Down,” said the athletes of today have even more impact than their predecessors did in 1968.

“So I think as long as our society is obsessed with sports and pour as much money and time into it, it will always create a platform,” she said. “These spaces have been kind of concocted to be this utopia free from politics, even though it’s always been there.”

Their actions in 1968 inspired admiration or hate for Smith and Carlos. And whether it’s a raised fist or a bent knee, the emotional reactions to African-American athletes protesting during the national anthem remain strong.

A version of this story appeared on WGBH.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?