California emerges as a leader at climate summit

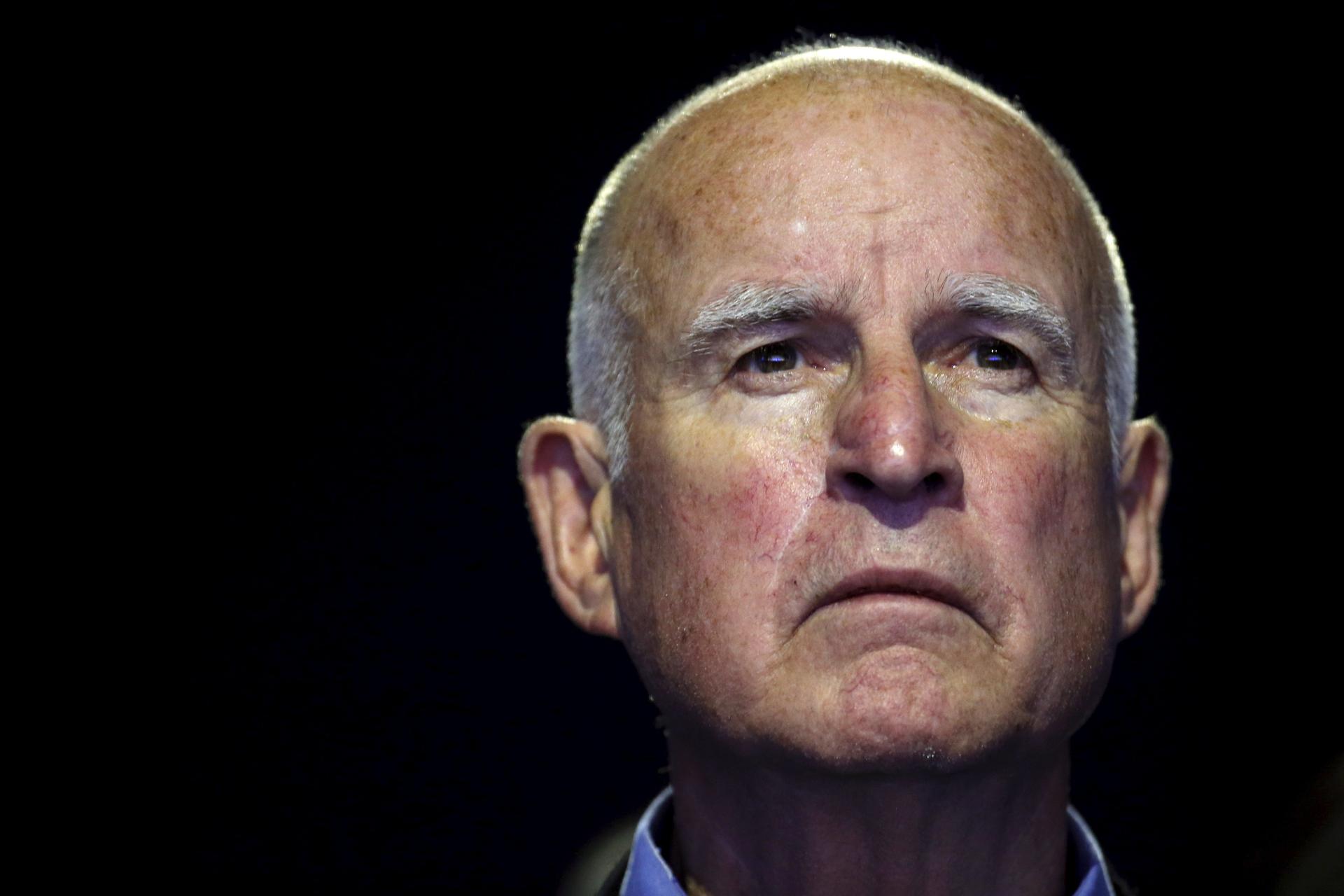

California Governor Edmund “Jerry” Brown attends a meeting during the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) at Le Bourget, near Paris, France, Dec. 5, 2015.

When President Donald Trump pulled the US out of the Paris climate change agreement last summer, cities, states and business leaders quickly tried to jump into the leadership void.

Chief among them was California Gov. Jerry Brown, who announced just weeks later he would gather leaders from around the world for a high-level climate summit in San Francisco.

“I know President Trump is trying to get out of the Paris Agreement, but he doesn’t speak for the rest of America,” Brown said in a video announcing the summit.

Related: Scientists say 25 years left to fight climate change

“We in California, and in states all across America, believe it’s time to act. It’s time to join together, and that’s why at this climate action summit we’re going to get it done.”

Brown’s mission since then has been to spur action at the city, state, local and business levels to make up for the lack of leadership in Washington as President Trump reverses key climate policies.

He, along with philanthropist and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, have launched America’s Pledge, which has secured commitments from thousands of sub-national actors to cut carbon pollution.

But the biggest test of how much a state governor can really lead on a global problem like climate change came this week as Brown convened the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco.

Heads of state, ministers, CEOs

By the time the curtain raised on the summit, Gov. Brown had assembled a group of high-level international leaders and regulars at UN climate negotiations.

Heads of state from Fiji, Barbados and the Marshall Islands were there, as were environment ministers from national governments, including Norway, Costa Rica, and New Zealand, and the CEOs of big multi-national companies like Starbucks, L’Oréal and Unilever.

Perhaps the most significant sign of Brown’s international clout was the size of the Chinese delegation at the summit.

“The fact that China sent a very high-level delegation to California, that was huge,” said Angel Hsu, an expert on China’s environmental policy at Yale.

Hsu pointed out the symbolism of having China’s top climate negotiator in attendance.

“Minister Xie Zhenhua has led the Chinese delegation for many years at these international negotiations,” Hsu said.

A partnership between China and the US paved the way for the Paris agreement under President Obama. Now, with President Trump having turned his back on climate action, Hsu said Brown seems to be the American half of that key relationship.

“It almost is like China and the US, they haven’t missed a beat in this bilateral partnership on climate change because California has really stepped in to fill the role,” Hsu said.

What does California’s leadership mean?

But California is just a state. It can’t officially negotiate at the UN as part of the Paris agreement process, which is still seen as the backbone of global climate action.

So how much do its efforts matter in a practical sense?

“It matters,” said Ji Zhou, head of the Energy Foundation China. He points out that California’s economy is bigger than most country’s.

“The top-five economy in the world, and also so many states, they continue to follow the Paris agreement,” Zhou said. “This is sort of encouraging.”

Sowing the seeds of action

Leading up to this week’s summit, Gov. Brown announced a slew of new climate policies to sow the seeds of action, including an ambitious law committing California to 100 percent renewable energy by 2045, and an even more ambitious executive order committing the state to full carbon neutrality by the same year.

At the summit, Brown extracted dozens of new promises from states, cities and businesses to cut their own carbon pollution. Ten new states and countries committed to phasing out coal use entirely, more than two dozen governments and businesses set targets for zero-emission vehicles, and 73 cities pledged to go carbon neutral by 2050. Promises were made to green ports, protect forests, and invest in battery storage for renewable power.

No one has tallied up the combined impact all these high-profile new commitments could have, but most summit attendees seem to agree that Gov. Brown’s actions have helped reinforce collective resolve.

“To me, Gov. Brown is a climate hero,” said Todd Stern, the head US climate negotiator in Paris.

“I think that this summit’s been very useful,” he said. “It’s a demonstration of activism, it’s a demonstration of will, it’s a demonstration of engagement by all sorts of sub-national players, and I think that’s all been tremendously useful.”

But, Stern added, “it doesn’t fill the gap of the absence of the United States at a national level.”

‘It doesn’t fill the gap’

Here’s just one example of why: Gov. Brown and former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg released a report this week showing that the voluntary promises made by more than 3,000 cities, states, business and non-profit organizations as part America’s Pledge will get the US less than half the way to the pollution cuts it promised in the Paris agreement. This was billed as a success story by the two leaders, and the report also contained a roadmap to getting the US much closer to its Paris goal. But it also points to the limitations of working with so-called sub-national actors, which include just 17 US states.

Unlike that patchwork approach, federal policies like the Clean Power Plan would have cut emissions in all 50 states.

“The US federal government can drive action all around the entire country, not just state-by-state,” Stern said.

Piecemeal solutions make it harder to reach a national climate goal, which in turn makes it harder for a nation — or a state like California — to push others to work harder to fight climate change.

Meanwhile, a growing body of research suggests that even the Paris commitments to capping rising temperatures are still too high to avoid a climate calamity.

That may be why Gov. Brown compared the task ahead to climbing Everest more than once during the summit.

“Everywhere you look there’s a challenge,” Brown said. “We’re at the basecamp of Mount Everest and we’re looking up to say, ‘There’s where we’ve got to go.’ It’s about that difficult.”

The real reckoning on how successful Brown has been on pushing climate action will likely come after he’s out of office, in 2020, when countries have to up the ante on their carbon-cutting pledges and make the next round of national commitments under the Paris agreement.