South-central Wyoming has some of the strongest winds in the United States. The Department of Energy estimates that by 2030, Wyoming has the potential to power the equivalent of 3.4 million homes.

Wyoming’s economy is dominated by coal, other fossil fuels and mineral extraction. The formula here has worked — residents in Wyoming enjoy among the highest per capita GDP in the nation. So naturally, there’s been some hostility toward new sources of energy that could threaten that.

“It’s a complicated history with wind,” says Jeremiah Rieman, director of economic diversification strategy for Wyoming Gov. Matt Mead. “I think you’re seeing a change. And certainly we’re hearing the message loud and clear, as we go through this economic diversification strategy effort, that wind and renewables need to be a part of that.”

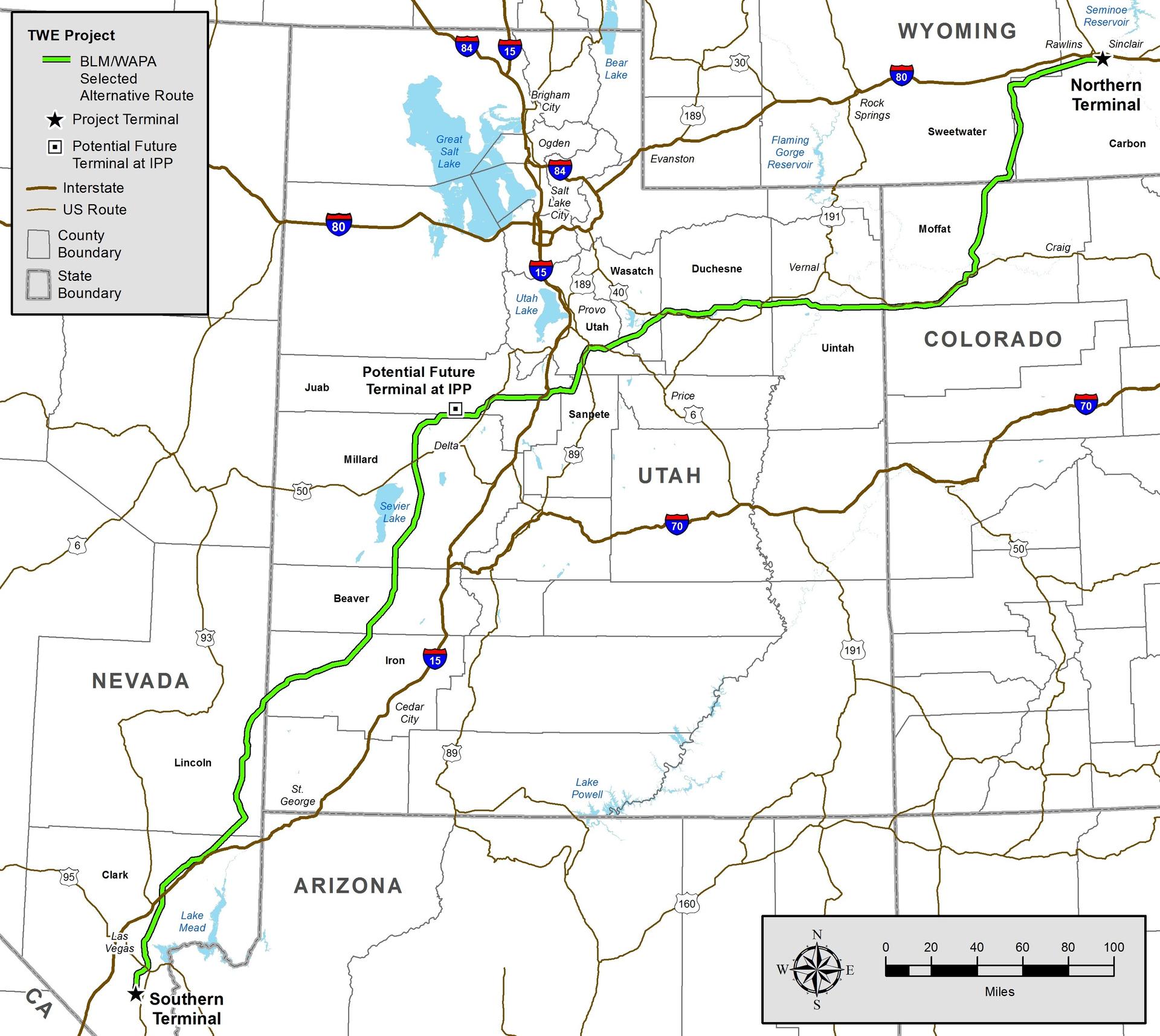

The push toward wind is playing out in a high-rise office building 100 miles south of Wyoming’s capital in Denver. There, TransWest Express is laying out plans to build a 730-mile transmission line across the American West. CEO Bill Miller points to a map and the start of the project — 1,000 wind turbines to be built on a ranch in south-central Wyoming.

“It starts there and runs a little bit west and then due south into northwest Colorado,” says Miller, tracing a line through Utah and then down south of Las Vegas.

If all goes according to plan, in three years Miller says the winds of low-population Wyoming will be bringing electricity to where it’s needed in California.

“To my knowledge, this is the largest transmission line development that has occurred in this country in probably 50 years.”

TransWest Express, which is part of the Anschutz Corporation owned by billionaire Phillip Anschutz, is looking to harness Wyoming’s wind because, well, it’s super windy.

The winds howl in southeast Wyoming because they’re rising at the continental divide, then pushing through a gap in the Rocky Mountains.

“So, if you remember your high school physics class there’s this thing called the Venturi effect where you narrow something and that naturally speeds up an air flow. And that’s really what we have here,” says economist Robert Godby, director of the Center for Energy Economics and Public Policy at the University of Wyoming.

Wyoming may have strong winds, but the state ranks just 16th for wind generation. Godby says Wyoming hasn’t exactly made things attractive for developers: “We have the only wind generation tax in the country, where we actually tax people who produce electricity with wind.”

Meanwhile, many other states are creating incentives for wind development, for example by creating renewable portfolio standards that require a state to obtain a certain amount of its energy from sources like wind and solar.

“I think it’s really unfair that Wyoming has this reputation for being hostile to wind or anti-wind,” says Jason Beggar, director the Wyoming Infrastructure Authority, a state entity tasked with developing large transmission projects.

“It’s not an anti-wind philosophy, it’s just the philosophy of the state — we tax our natural resources to fund government.”

Beggar says it’s tough to build in Wyoming because roughly half of the state is federally owned land.

“So when you go to Texas, or you go to Iowa, you’re generally just negotiating with a landowner, whether it’s a farmer, whomever,” says Beggar. “Well, in Wyoming, you have to file permits with the federal government and that includes things [like] land use, wildlife mitigation, mineral disturbances. There are factors and factors and factors.”

Beggar says the Trump administration has shown a “willingness” to cut red tape and move things along more quickly. Meanwhile, conservationists and environmentalists have bristled at the rollback of regulations.

There’s another challenge facing Wyoming wind: climate change skepticism. Coal burns dirty and produces a lot of greenhouse gasses. Many states are pushing renewable energy to move away from that. But in Wyoming, it’s complicated.

“Climate change is a pretty tough subject to talk about with some people because it’s a threat no matter how you look at it,” says Robert Godby. “It’s a threat to world climate, it’s also a threat to people’s livelihoods [in Wyoming]. And those two things are kind of in conflict. If you’re a state like Wyoming where you produce so much fossil fuel, in particular coal, that’s threatened by any sort of climate change policy we might put in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Wyoming’s governor, Matt Mead, professes skepticism on climate science, but not on the markets, which are moving away from dirtier-burning fuels like coal. That’s why he’s pushing for a more diversified economy.

At the end of the day, the debate in Wyoming is really about jobs.

Bill Miller says that when people learn about the tax revenues and jobs their transmission line and wind farm will bring to Wyoming, they like that.

“These are good, high-paying jobs. And when we finish this project, the permanent jobs are going to be roughly 150 people, well paid, fully-benefitted jobs that are really a boon to those communities,” says Miller.

Wind projects in Wyoming won’t come anywhere close to creating enough work to replace the coal industry. Still, the jobs are an important part of the state’s broader diversification strategy.

“Roughly 60 percent of our youth, between the ages of 18 and 24, will not be here 10 years from now, and that’s a trend we would like to see disappear,” says Rieman.

Whether new opportunities come from digging up coal or harnessing the wind, for job seekers in Wyoming, that detail may be of secondary importance.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!