The early impact of solar tariffs: Fewer American projects, fewer American jobs

Workers install panels at a solar farm built by Cypress Creek Renewables in Laurinburg, North Carolina. The company has cancelled projects in 10 states since new tariffs were implemented.

Cypress Creek Renewables builds and manages large-scale solar farms across the US, which supply power to utilities. The company’s CEO Matt McGovern said “it’s very difficult, if not impossible” to find all of the solar equipment it needs from US manufacturers.

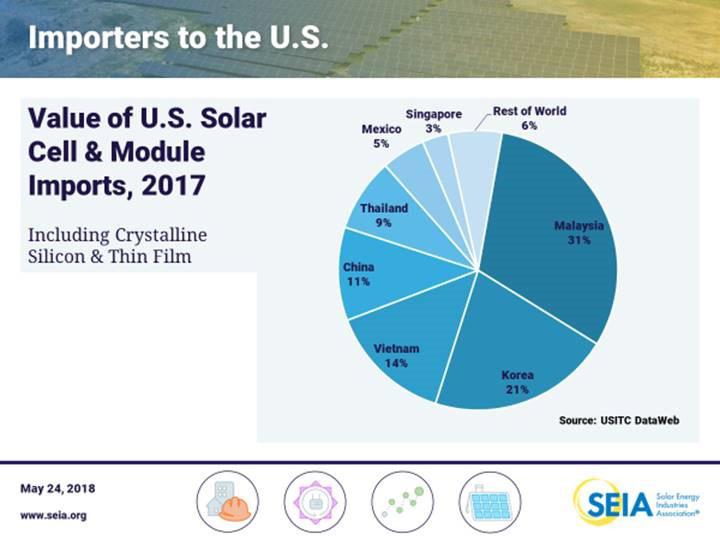

So, McGovern says he has to turn to Asia to import equipment: “Malaysia, Vietnam, South Korea, some out of China.”

Since January, imports of solar cells and modules (basically a panel) have come with a 30 percent tax.

“It’s been meaningful,” McGovern says. “The impact, direct for us, has been the cancellation or delay of around a gigawatt-and-a-half of projects.”

That could’ve supplied power to about 250,000 households for a year.

Tariffs, basically taxes on imports, have become a favored tool of the Trump administration. President Trump is now asking for an investigation into whether imported autos pose a threat to national security. If it’s found they do, the Trump administration could impose tariffs.

The administration has already imposed tariffs on steel, aluminum and washing machines, and has been threatening a lot more. Back in January, the administration imposed tariffs of 30 percent on imported solar cells and modules, aimed at Chinese and Asian competition. The tariffs decrease annually, falling to 15 percent in the fourth and final year.

It’s only been four months, but the US solar industry is putting off a lot of projects this year because of the tariffs, says Abigail Hopper, the CEO of the Solar Energy Industries Association.

“So what does that translate to in terms of jobs? We think about 23,000 jobs will either be lost, actual people will lose their jobs, or jobs that won’t be created [this year],” Hopper says. “Companies would have grown and would have invested in their workforce, and they’re not going to do that now because of the impact of these tariffs.”

Hopper’s association is working with a bipartisan group in Congress to repeal the tariffs. She’s not optimistic. Hopper says their best chance could be when the United States International Trade Commission re-evaluates the tariffs in two years.

“Two years is an awfully long time,” Hopper says. “And the worst part about it is that it’s just opportunity lost, it’s opportunity lost for no apparent gain.”

Not everybody agrees with that. Two American companies argued last year that Chinese-owned firms were engaged in unfair competition, over-supplying the US with solar cells and modules that have been heavily subsidized by the Chinese government. They argued that China’s solar strategy has nearly wiped out American manufacturing.

The Obama administration had already put tariffs on solar imports from China; the Trump administration broadened them because China was getting around the duties by setting up shop in other nations.

One of the two companies that brought last year’s trade case was Oregon-based SolarWorld Americas. A month ago, the Silicon Valley based company SunPower bought it. SunPower’s CEO Tom Werner said the tariffs made the Oregon factory an attractive acquisition.

“I felt it was better to swim with the current, so to speak,” Werner says, referring to the Trump administration’s policies that “strongly desire” American manufacturing.

But large companies like SunPower are global — the company is majority-owned by the French company Total — and SunPower also builds solar cells in the Philippines and Malaysia. And Werner said its Asian manufacturing isn’t relocating to Oregon.

“The challenge of moving large-scale manufacturing anywhere is that you’ve invested, in our case, over a billion dollars, and you’ve not gotten the full return on that investment,” Werner says.

So, if his company now manufactures in Asia and Oregon, where does that leave Werner on the tariff question?

“I’d say that my experience as an operator of a company is that tariffs are difficult to work,” Werner says. “They get implemented quickly and then they’re super hard to react to, and so they distort the market. So I’d have to say as an operator, I find them difficult.”

He says his company is also now paying between $1.5 million and $2 million a week for import tariffs.

Werner adds that tariffs focus on yesterday’s battle: “I think the objective should be to win in the next wave of innovation in solar, which is the integration of solar with batteries.”

The other company that brought the trade case was Georgia-based Suniva. The company, which is majority Chinese-owned, didn’t respond to interview requests.

MJ Shiao, who researches renewables and emerging technologies with the research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, agrees that tariffs are a “fairly crude” way to encourage American manufacturing.

Shiao says the US needs a long-term vision, not tariffs that phase out over four years.

“These other countries like China have invested in their manufacturers, whereas in the US, we don’t really have a clear and coherent solar manufacturing policy,” Shiao says.

Shiao would like to see more workforce development programs and government incentives to invest in research and development in tomorrow’s innovations.

And remember, the argument over solar tariffs isn’t just about jobs; it’s also about climate change. Shiao said that as solar imports become more expensive, fewer will get installed. And fewer solar panels could mean continued reliance on fossil fuels in the short-term, and more greenhouse gas pollutants in the atmosphere.

“Around 7.7 gigawatts of solar energy that could’ve been installed over the next five years — that is no longer economically attractive,” Shiao says.

That would’ve been enough energy to supply all the households in a city roughly the size of Chicago.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?