New book looks at medical cures now considered ‘quackery’

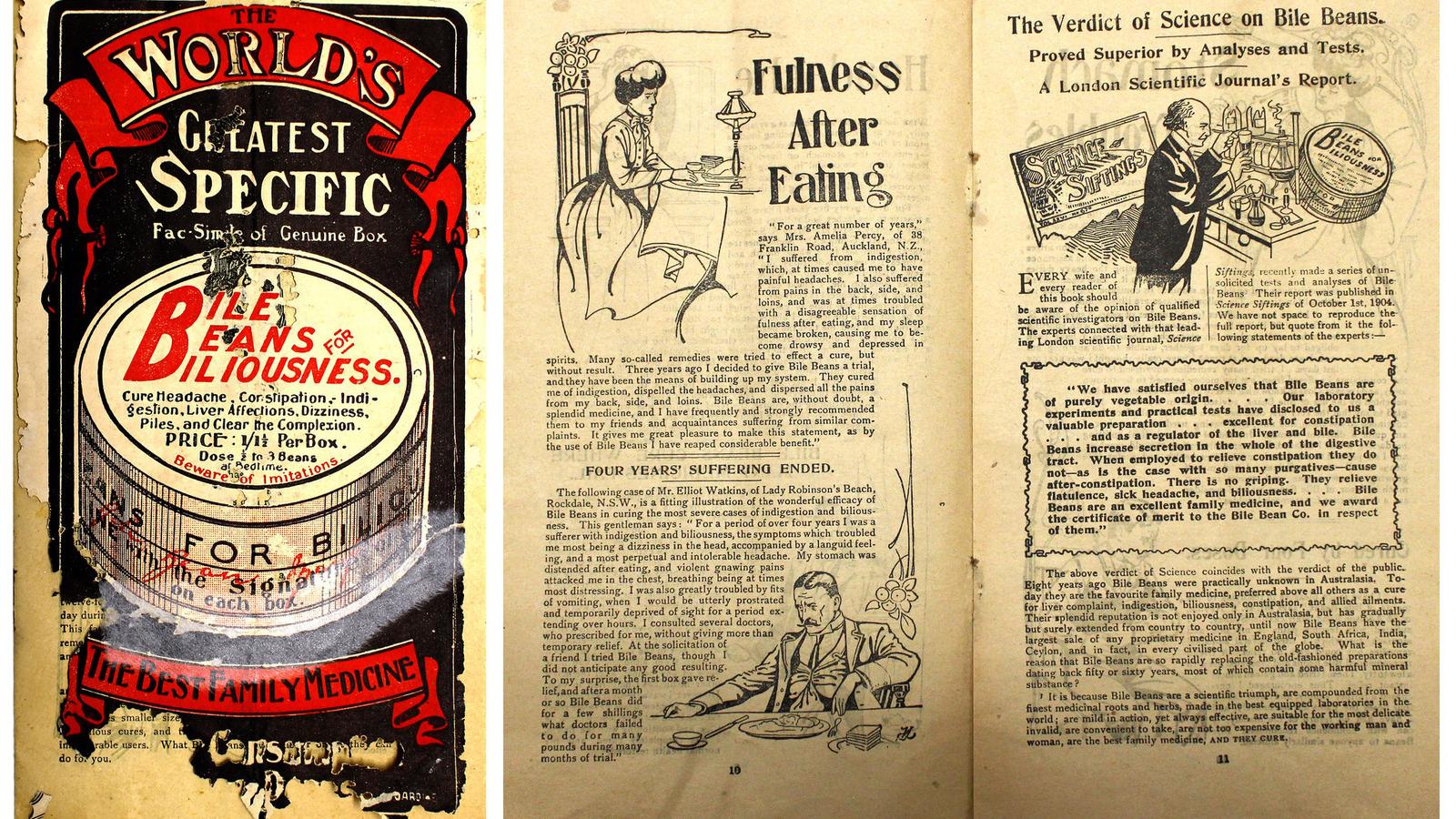

In 1908, New Zealand Parliament passed the Prevention of Quackery Act to defend against claims such as the one featured in this leaflet: "bile beans" that claimed to cure a vareity of ailments, including indigestion, headaches, pimples and sleeplessness.

Placing red-hot irons on someone's temple for headaches. Drinking mercury for syphilis. Rubbing pimples on dead bodies for acne. All of these remedies to various maladies seem ridiculous now, but at one point they were not.

They are just some of the some of the crazy “medical cures” that are highlighted in a new book written by Lydia Kang: “Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything.”

In addition to exploring centuries of misguided medical treatment, Kang’s book also uses modern-day scientific evidence to determine their efficacy. Although the book features numerous stories about the unorthodox pathways to health, Kang says she heard many more during her book tour.

“There were a lot of people who I’ve met over the course of this last year who would come up to me at book signings … and tell us what their grandparents used to do or their own parents used to do. And so all these other sort of old-timey treatments are coming out through the cracks,” says Kang, a practicing physician based in Omaha, Nebraska, “who has gained a reputation for helping fellow writers achieve medical accuracy in fiction,” according to her site.

Some treatments (some of which are highlighted here) gave birth to phrases that are part of our everyday lexicon, such as like “mad as a hatter” or “blowing smoke.”

The first phrase is related to the consumption of mercury, which was thought to be able to cure a variety of issues. Often it was taken in the form of mercury salts. It was quite common for people in the felting industry to use mercury to power them through long shifts of making large top hats, Kang says. Many of the people who consumed the mercury became sick from poisoning.

“It had a really horrible effect on the body, which is that it caused mercury toxicity,” Kang says. “People would have terrible diarrhea and get these awful sores in their mouths and their stomachs. And sometimes it made them mad as a hatter.”

The term “blowing smoke” actually originates in London during the 18th century, when there was a belief that tobacco smoke could actually revive drowning victims — but the treatment had an enema-like application. There were kits on the banks of the Thames River, Kang says, that contained a bellows and a device to light tobacco.

“They pull your pants down, lift your skirt up, and they get that bellows and try to revive you,” Kang says. “So my guess is that if you’re actually still conscious, it will freak you out into actually trying to run away from the treatment. But that didn’t last very long. People realized after a while this wasn’t the best way to revive people from drowning. But it was used for a while. It’s just hard to believe.”

It was also in London where the barber pole originated. It stems from an odd medical practice in which bloodletting was performed by “barber-surgeons” at the instruction of a doctor to prevent or cure a number of illnesses or diseases, Kang says. The barber would tie a tourniquet around a patient’s upper arm. The patient would squeeze onto a pole to help with the backflow of blood. The barber would then cut the patient’s vein and allow the blood to drip into a bowl that would be set on a windowsill.

“They would take the tourniquet and any kind of bloody rags. … [T]hey’d be drying outside and flapping in the wind,” Kang says. “So you’d see these sort of white-and-red striped pieces of cloth flapping in the wind with the pole and the bowl."

That's where the modern red-and-white striped barber pole comes from, Kang says.

One of Kang’s favorite chapters delves into the medical practice of people touching dead bodies, thinking that the good health of one person could be transported to another.

“Everybody thought that the human body had this sort of magical power in it,” Kang says. “And if you could sort of capture that power at the time when someone died, you could impart that health onto yourself.”

As an example, she mentions the practice in England during medieval times of people rubbing their pimples and sores on people who were freshly hung from the gallows after an execution.

There was also something known as “king’s touch” that went from the 1200s all the way to the 1800s in England and beyond. Believing that kings had divine powers, people would take part in ceremonies in which the king would touch whatever body part was ailing them. They would then receive a special gold coin that people would rub on themselves to continue the healing process.

Kang says it is only a matter of time until people will look at our own modern-day medical practices and shake their heads the way that we do now at various treatments.

One such example, she says, may come from how we currently perform mammograms to detect breast cancer.

“We’re going to look back and say, ‘You used to take the tissue and squash [the breast] between two plates and get these images to try to find cancer when, nowadays, we can wave a wand, or you have a blood test at birth,’” Kang says.

“There’s just so many other ways that we can’t even begin to imagine how we are going to be able to save lives and find diseases early or prevent them. And they’re going to look back right now at what we’re doing, and they’re going to laugh at how crude it was.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.