The ozone hole over the Antarctic is beginning to fill up. Here’s the bad news.

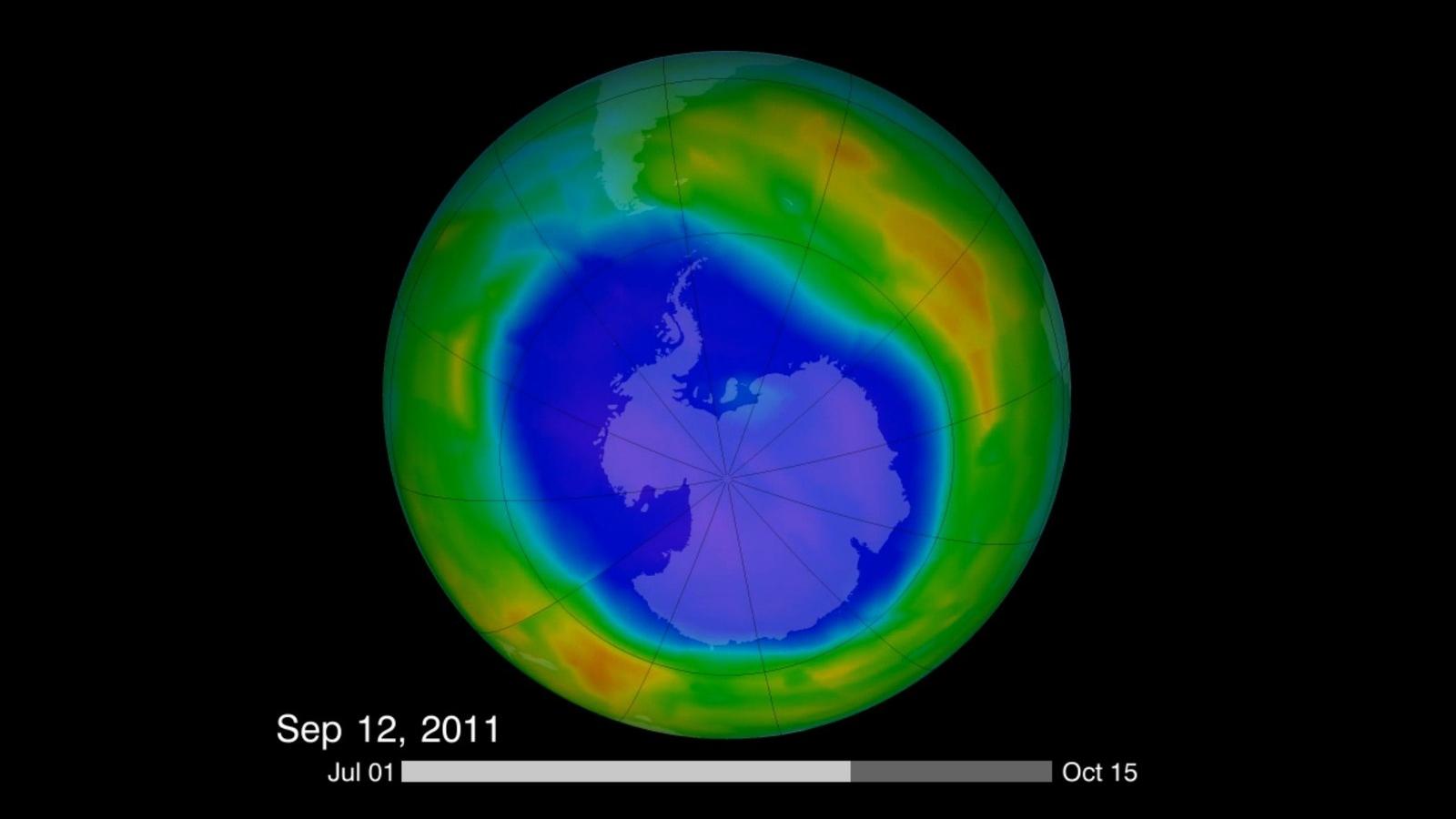

This image is from a video made in 2011 that compiled visualizations of the Antarctic ozone hole. Recent findings have shown that the hole is filling up — while other parts of ozone remain on the decline.

Before the term global warming entered our collective lexicon, environmentalists and scientists had expressed major concern over the depletion of the ozone, the layer of gas that protects the Earth from extremely harmful solar ultraviolet (UV) rays.

This heightened awareness led to the international adoption of the Montreal Protocol in 1987, in which major restrictions were placed on products that contained chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) — thought to be the biggest culprit in the matter.

Now, three decades later, an international team of researchers has revisited the issue with a paper that was recently published in the journal, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Their findings produced a case of good news/bad news, says Jo Haigh, an atmospheric scientist and co-director at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London.

It turns out that the CFC ban in the Montreal treaty has been doing what experts had hoped it would.

“The ozone hole over the Antarctic is gradually filling up,” Haigh says. “So, it is getting a little bit less severe. So, that's the good news and the atmosphere responded as we expected when the chlorofluorocarbons were banned.”

Ready for the bad news?

The future isn't so bright for the ozone near the equator and in the middle latitudes, where the layer is continuing to decline — while leaving researchers like Haigh to scratch their heads over the situation.

“We've got to think about why it's going away and if we can stop doing whatever we're doing to make it go away — and we don't really understand what that is,” she says.

Haigh says there are two major theories to which researchers have gravitated.

The first centers around climate change. Although recent weather patterns have been warming the lower atmosphere, they have been causing a cooling effect in the stratosphere, which changes the circulation of the air.

“That flow is going faster and so this low ozone air is coming up and being transported from the equator to middle latitudes,” Haigh says.

The second theory stems from chemistry and things that are known as very short-lived substances (VSLS) that contain chemicals such as chlorine and bromine. These substances can have a similar harmful effect to the ozone as CFCs.

The findings of Haigh’s team also remind us that we should take precautions to fend off harmful UV rays — especially in the summertime — by wearing longer clothes and hats, Haigh says.

“In the Antarctic, the ozone depletion was very marked, but the sun was not so intense there,” Haigh says. “If you go down to the equator where we all live around sort of 50 degrees north, then the radiation from the sun is much more intense. So, if you weaken the ozone layer, then the scope for more effect from the sun — and in particular, the UV — is affecting DNA and anything that’s living.”

She says that this is especially true for “white people who go around with not many clothes on,” who will be a higher risk for skin cancer.

Going forward, Haigh and her colleagues will continue to monitor the ozone’s measurements.

“Perhaps it'll just mend itself, which would be nice, but if it doesn't, then we've got to try and think why it's happening and try and stop it,” she says.

This article is based on an interview on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.