As the Arctic warms up, a ‘new ocean’ is bringing new commerce to the top of the world

Nome, Alaska, mayor Richard Beneville is excited about the opportunities that climate change is opening up for Arctic communities. In recent years less ice has meant more tourism for the town of about 3,800 people near the Bering Strait between the US and Russia. “If people can get there, they’ll go,” Beneville says. “Tourism according to Dicky!”

This story is part of our series The Big Melt. It comes to us through a partnership with the podcast and radio program Threshold, with funding support from the Pulitzer Center.

Richard Beneville never figured to end up in Alaska. He was a song and dance man in New York City.

“My ambition all my life has been the theater,” he said. “Give me a microphone and a top hat and a pair of tap shoes. I started tap dancing when I was 6.”

But Beneville developed a drinking problem. His family intervened and sent him to live with his brother in Alaska.

He never looked back. Thirty-six years later, he’s found himself in a job he could never have imagined back in New York.

“I’m mayor of Nome. And it’s a kick in the ass!”

Nome is a town of about 3,800 people on the southern side of the Seward Peninsula, the knob of land way out on Alaska’s western coast that forms the eastern side of the Bering Strait between the US and Russia.

“This is a cool town,” Beneville said, adding, “a really cool town. And it’s a cool time to be mayor because so many exciting things are happening.”

Things like “the opening of the Arctic. I mean, we could start there,” he said.

Related: Ice is us: Alaska Natives face the demise of the Arctic ice pack

“What’s happening is the increased accessibility of going through the Bering Strait for a longer period of time each year because of climate change and the opening up of what is referred to by many as a new ocean. And that would be the Arctic.”

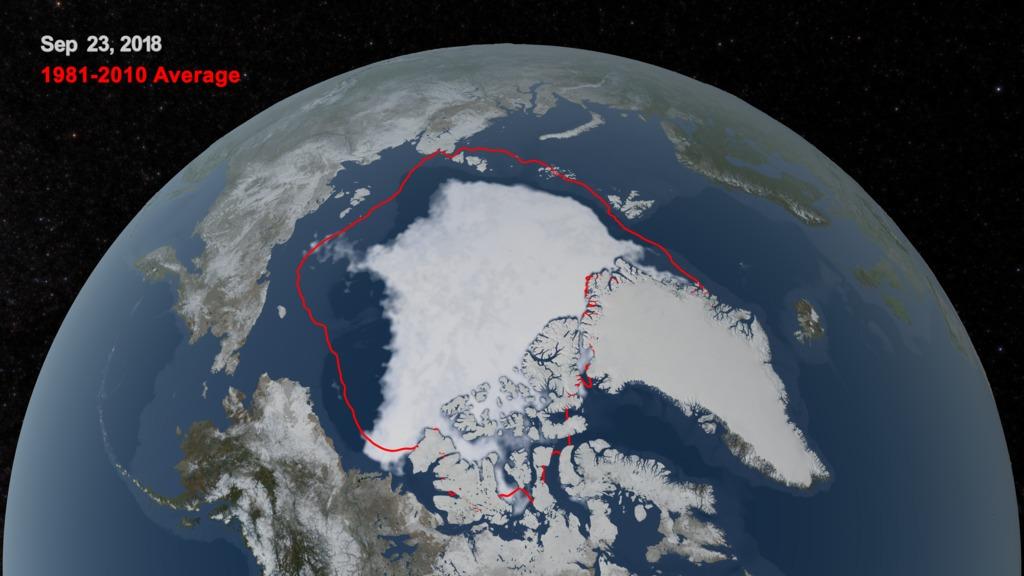

The Arctic Ocean has always been largely impassable for most ships, locked up in ice year-round. But with climate change, the Arctic region is warming up faster than any other part of the planet. Polar ice is receding quickly, especially in the summer months, which means more ships are able to come to the region, including more and bigger cruise ships. Tourism is booming in many Arctic communities, with cruise companies offering trips to watch polar bears, go dogsledding and even view receding glaciers before they disappear.

“If people can get there, they’ll go,” Beneville said. “Tourism according to Dicky!”

Not all Arctic communities are excited about that. Many towns up here are tiny, so it doesn’t take many visitors to overwhelm the locals. Ships full of tourists can also bring pollution and disrupt wildlife. But cruise ships can bring a lot of money, too, and Beneville welcomes them to Nome.

“It’s an opportunity for us to shine — not just Nome, but the region,” he said.

In 2016, a ship called the Crystal Serenity became the first large cruise ship to navigate the Northwest Passage, the fabled route over Alaska and through the high Arctic Canadian archipelago. It took 32 days, and Nome was one of its first stops.

“Now, we have a cruise that begins in Seward, Alaska,” Beneville said. It “comes up, spends — as I say, you know, 800 people come to tea — and then goes on across Northwest Passage, Greenland, and down the eastern coast, Nova Scotia, all of that, and then ends in New York City. Well, now, that really is an interesting thing.”

Beneville wants to deepen Nome’s port, so even more big ships can dock there. And he’s hopeful those ships will bring more than tourists. He sees a future with Nome as a major way station, with ship traffic driving growth in population, jobs and prosperity.

Related: An Alaskan village is falling into the sea. Washington is looking the other way.

He’s not blind to the downsides of climate change here. But, as mayor, Beneville’s job is helping his community, and he says if he can harness the forces of climate change to do that, he will.

It’s a confusing mix of threat and opportunity here in Nome, and it’s part of a story that’s unfolding all around the Arctic.

Melting ice, breaking ice

Halfway around the world, captain Pasi Järvelin stands on the bridge of the icebreaker Polaris in Helsinki, Finland. Icebreakers are like the offensive line of the ship world. They power through the ice-cutting paths for research boats, oil tankers, military ships — basically, any craft hoping to travel through polar oceans may need help from an icebreaker.

The bridge of the Polaris is so far above the deck that you take an elevator to get there. It’s sleek and modern, with huge, tinted windows and dozens of screens all around. And the captain’s seat rolls forward and locks into place when the seas get rough or the ice piles up all around the ship.

“It’s a quite masculine job, yes, I would say,” Järvelin said with a chuckle. “It’s very exciting, and I like icebreaking a lot.”

A lot of people in Finland like icebreaking.

Related: In Iceland, a shifting sculpture for a changing Arctic

“We dare to say that we are the world champion in icebreaking,” said Tero Vauraste, the CEO of Arctia, a state-owned icebreaker company that owns and operates the Polaris. “There are approximately 130 icebreakers in the whole world, and around two-thirds of those have been designed and built in Finland.”

And Vauraste says icebreakers are actually a growth business these days.

“I’m often asked, ‘Well, the ice is melting, who needs icebreakers?’” he said. “But it’s actually vice versa … There is less ice, but it doesn’t mean that the conditions get easier. They actually are more variable.”

As conditions change, icebreakers are leading the way through the Arctic Ocean, breaking open new trade routes at the top of the world.

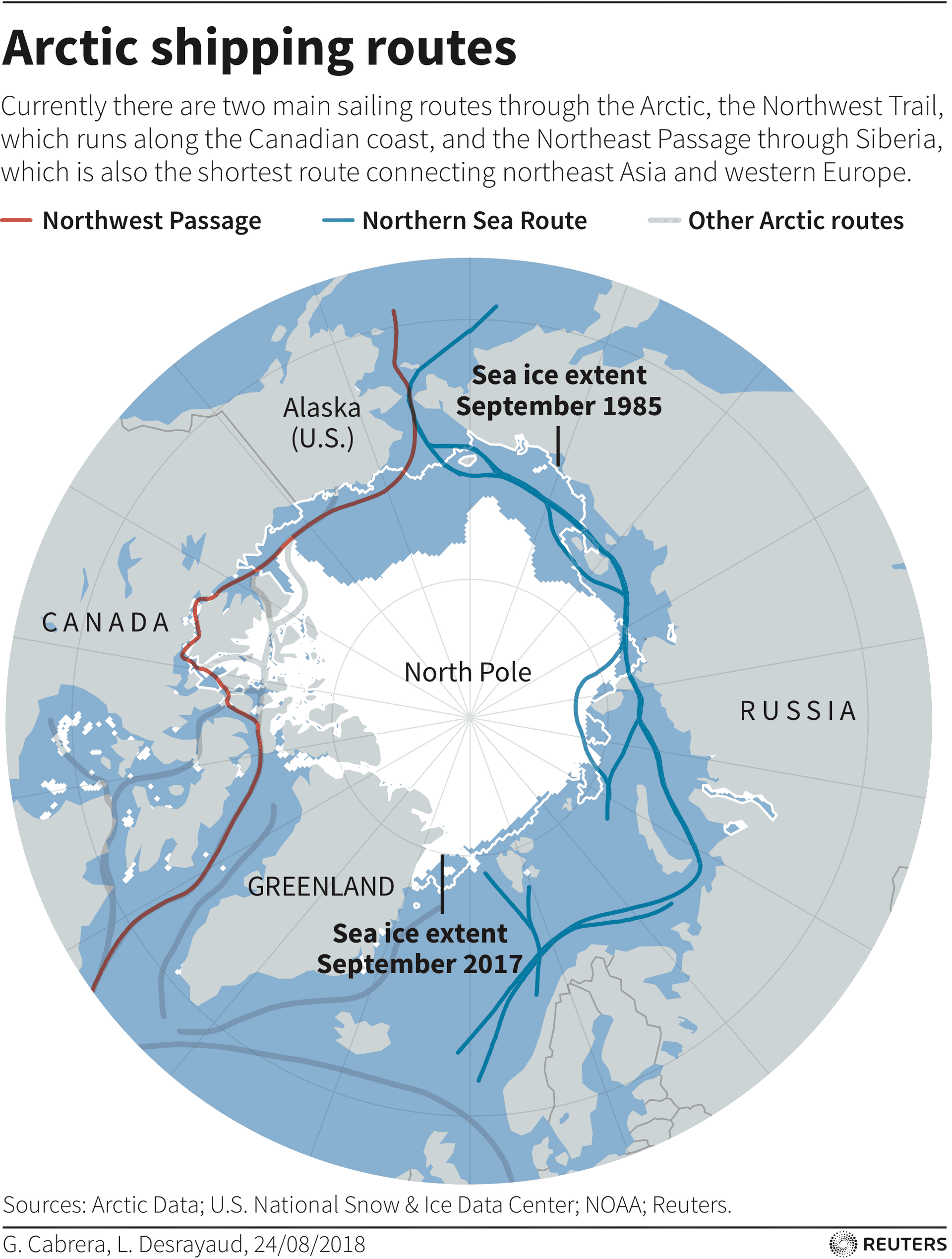

If you’re looking to cross the Arctic by ship right now, you basically have three options.

One is the route Richard Beneville described — the Northwest Passage through the high Canadian archipelago.

On the other side of the globe, there’s the Northern Sea Route along the Arctic coast of Russia and Scandinavia. Russia is actively developing this route as a way of connecting Europe to Asia and making money from the ships that pass by.

But if sea ice continues its precipitous decline, as it’s likely to do, ships might someday be able to avoid both of these routes and use a third one — the Transpolar Sea Route, more or less straight across the top of the world.

And as in Nome, this new access likely will bring more ships.

“There will be [an] increase in the transit traffic, increase in tourism,” Vauraste said. “And of course, the great investment potential, which is worth one trillion. One trillion dollars … spread around the Arctic.”

But all that potential cash isn’t just about traveling through the Arctic.

The Arctic is not a park to be preserved

A 2008 report from the US Geological Survey found that the Arctic is the biggest area of unexplored petroleum deposits left on the planet, with huge potential reserves both onshore and under the sea. Countries and companies around the world are eyeing those deposits, trying to figure if or when or how they might go after them.

Canada currently bans offshore oil and gas development in its part of the Arctic. The US had a similar ban put in place by former President Barack Obama, but it was overturned by President Donald Trump. In late October, the US gave provisional approval for a project off the North Slope of Alaska that could produce the first oil to be extracted from US Arctic federal waters.

“But the biggest investment potential is in the Russian areas,” Vauraste said. “About 20 percent of the Russian [gross domestic product] is coming from the Arctic areas.”

Vauraste says Russia is already extracting huge amounts of natural gas in northern Siberia, then liquefying it, putting it into tankers and shipping it to Europe and Asia along the Northern Sea Route.

And fossil fuels aren’t the only resources in the Arctic. There are also valuable minerals and metals. Which raises a tough question — is there a danger in profiting off of the global disaster that is climate change?

“I’m not going there,” he said. “Because I’m saying that the Arctic is not a park to be preserved. Nor is it a dirty area where big nasty companies conduct their dirty business. But it’s an area where you need to have a holistic approach on whatever you do.”

Vauraste says holistic means thinking not just about profit but also about environmental impacts and the people who live in the Arctic.

But is there a holistic, environmentally sound way to extract oil and gas? There are certainly ways to drill that are more or less damaging, but even if we don’t spill a drop in the process, we’ll still burn it. And that just speeds up the warming of the Arctic, a process that’s already moving fast.

Related: Arctic permafrost is starting to thaw. Here’s why we should all care.

“The ice is receding and melting in the Arctic Ocean. It will probably be gone in 20 or 30 years for summertime,” said René Söderman, who heads up Arctic policy initiatives for Finland’s foreign service and serves on the Arctic Council, a forum for collaboration between the eight Arctic countries and six Indigenous organizations.

And as the ice cover declines, Söderman says interest in the region is growing quickly, not just among neighboring countries.

“You just have to look at the globe and see who might have interests to deal with when that happens,” he said. “Not only the US and Russia. China very recently published its Arctic strategy.”

But Söderman says it would be wrong to characterize all of this activity as simply a mad dash to cash in on the Arctic as climate change makes it more accessible. He says there’s also a lot of cooperation and negotiation in the region. Arctic Council members have agreed to help each other out on search and rescue missions and potential oil spills. They also collaborate on all kinds of scientific projects.

“So, from this point of view, you could maybe say that the Arctic Council is a confidence-building measure,” Söderman said.

That will be important, because if — or when — the Arctic becomes fully navigable in the summer, it could bring waves of change and not just in the way goods are shipped around the world. Observers say it could rearrange alliances between nations and shift the basic geopolitical order of the whole planet.

There are also big concerns about pollution. Any oil spilled from drilling or ships would be extremely hard to remove from frigid Arctic waters.

That’s something that definitely worries Söderman.

“What is concerning is that when that ice recedes from the Arctic Ocean, probably it will mean more traffic on the sea routes, and that will increase the risk of environmental accidents,” he said.

A whole new world is opening up in the Arctic as the ice recedes. There are dangers and opportunities. And for many people, like Polaris captain Jarvelin, there’s the thrill of blazing trails through a new frontier.

“Like they say in ‘Titanic,’” Jarvelin said about when he’s breaking up ice, “I’m the king of the world.”

You know your captain is confident when he has no qualms about referencing the “Titanic” while standing on his ship.

The greatest challenge here in the changing Arctic, though, may not come from the ice, but the lack of it. We need polar ice to help keep the planet cool. But as the Arctic warms and the ice melts, the process triggers lots of feedback loops — processes in which warming creates new conditions that just contribute to more warming. And this is another one — the warming Arctic is giving us access to more of the very fossil fuels that are causing the warming.

In the long run, climate change will almost certainly be humankind’s most expensive folly ever. But as economist John Maynard Keynes famously said, in the long run, we’re all dead. And in the meantime, there are lives to be lived and money to be made in a changing Arctic.

Amy Martin is the executive producer of the podcast and radio program Threshold.