Waiting for asylum, migrants in limbo grow desperate

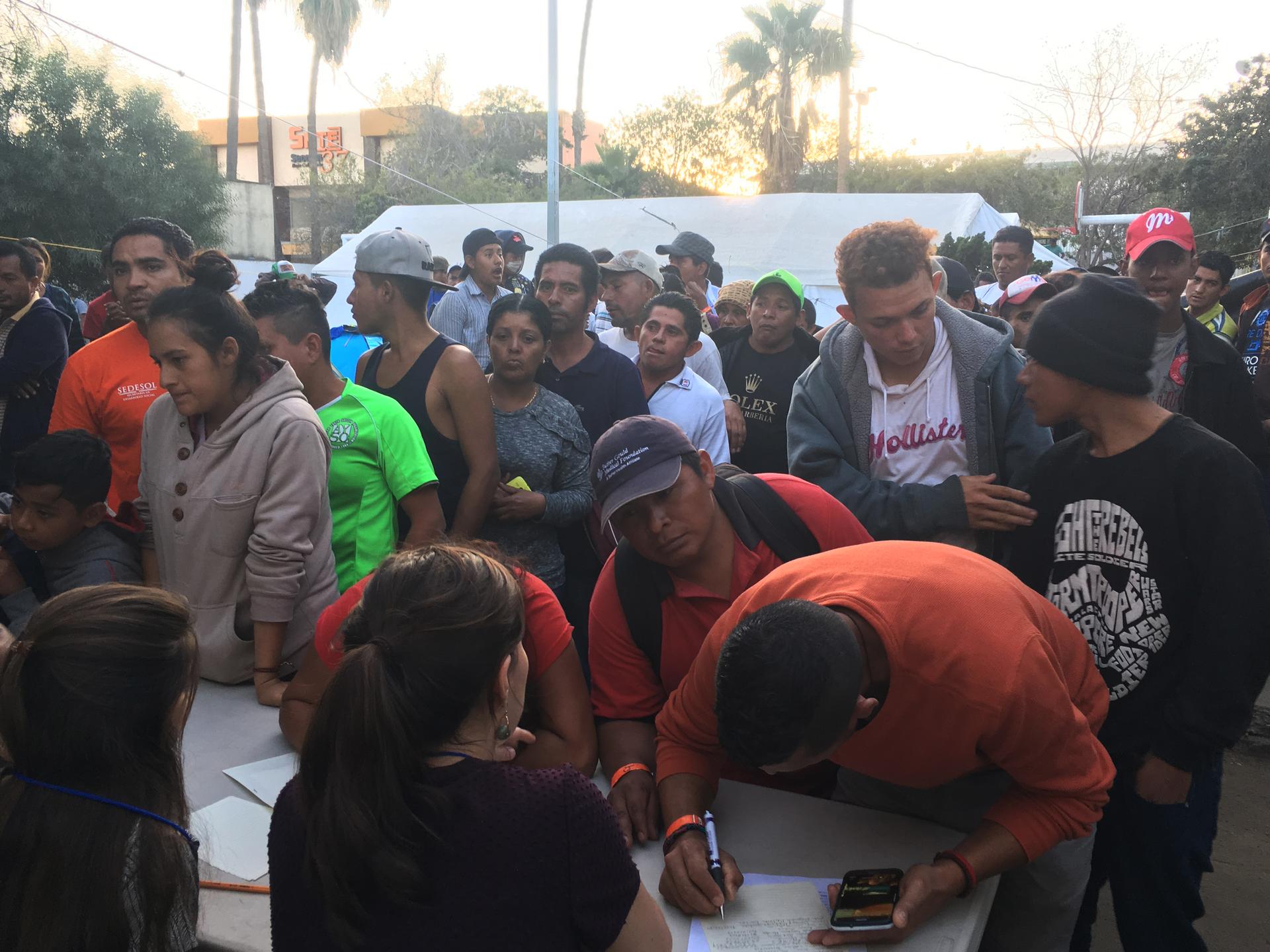

Migrants from Central America trying to reach the United States wait to receive food in a temporary shelter in Tijuana, Mexico, Nov. 18, 2018.

Blankets, tarps and people cover most of a municipal sports complex in Tijuana, Mexico. Men mill around in groups talking. Kids play on a jungle gym. Mothers breastfeed their babies. It’s the temporary shelter for around 3,000 Central American migrants.

This group of migrants has traveled for more than a month to get here, many sustained by their belief that God will open a path for them to reach the US. They’re just a half-hour walk away. But getting in seems more distant than ever. Now, they are weighing their options — none of them good — about what to do next.

Related: After an ugly campaign for immigrants, some midterm wins spark a glimmer of hope

Mirna Amaya rests on a blanket. Her 7-year-old daughter Helen plays with a doll nearby. She is thinking about applying for asylum but isn’t sure. She plans to wait until even more migrants arrive and then go to the border as one big group — like the migrants did in Guatemala when they crossed into Mexico a month ago.

“There has to be a deal to let us in. Because there are too many of us,” she insists.

Ernesto Amaya [no relation to Mirna Amaya] is skeptical this plan will work. He lived in the US for more than seven years. He has two daughters in Ohio, ages 6 and 10. He last saw them six months ago, right before he was deported for selling guns illegally.

“I want to see my girls again. That’s what I’m here for,” Amaya says.

Related: One Guatemalan child’s memory of trying to come to the US: ‘They took my dad and locked him up’

But Amaya says there’s no chance the US will let him in. So he’s going to wait a few months and work in Tijuana to save some money. Then he says he will try his luck crossing the border illegally.

“These people think they are just going to go down there and get some paper or they are just going to cross. I know that’s not true,” Amaya says.“[US officials] are not going to give papers to them. They are just going to cross, and get to immigration jail. And get deported.”

Amaya is right on one account. Only a small percentage of people who claim asylum in the US actually get it.

But the migrants here feel so close to their dream of reaching the US. They are not going to give it up. Still, they’re desperate for information. Most of them have not talked to a lawyer and don’t know what the process is for applying for asylum and whether they qualify.

So when a small group of lawyers and law students from New York University show up at the shelter, hundreds of people crowd around. There are so many people that a volunteer on a loudspeaker implores the migrants to get into two lines and wait their turn to talk to the lawyers. The problem is, they don’t all speak Spanish. For the next hour, I help one of the attorneys field questions.

The questions are basic: How long does it take to fight an asylum case? How long does asylum last, if you get it? Many of the migrants want to know if they have a strong case. But there are not enough lawyers to do that kind of personal consult.

At one point, a Spanish-speaking law student gets on a loudspeaker.

She yells out that for those seeking asylum in the US, the first step is to go to the official port of entry and ask for a number. This generates more confusion. A number? The lawyer says there is a waitlist to ask for asylum, and the number signifies where you are on that list. People are still confused, but the next morning, hundreds go to the port of entry. It’s at the bridge connecting Mexico to the US.

There, a woman volunteer writes down everyone’s information in a notebook and gives them a number. This is the list to enter the US legally and ask for asylum. There are more than 3,000 people waiting on that list, which started in January.

The woman with the notebook tells people to come back in three weeks to check in. But it will likely be months before their number comes up. US border patrol is only accepting around 90 asylum-seekers a day because it says they can’t process more.

After getting their number, Marjorie Castillo and her husband Derian Carbajal walk away, heads down. They left Honduras five weeks ago with their three young daughters. Carbajal says he got death threats because he refused to join a gang. They want to enter the US legally at a port of entry and ask for asylum, but they are getting desperate.

Related: After Pittsburgh, Jose Antonio Vargas asks, ‘Who is an American?’

“The truth is, I don’t think we can wait [in Tijuana] much longer. Our daughters are suffering. In the shelter, there is no water, no food, no medicine,” Carbajal says.

He says he and his wife are considering crossing the border into the US illegally and asking for asylum.

That’s how generations of migrants have done it before them.

But at the beginning of November, President Donald Trump signed an order that basically makes migrants who enter the country illegally — outside of a port of entry — ineligible for asylum. Castillo and Carbajal didn’t know about this, and it worries them even more.

Back at the sports complex, people are restless, anxious. One man approaches me.

“Of all the people here, how many do you think are actually going to get asylum?” he asks.

“I’m not a lawyer,” I say.

“But what do you think?” he insists.

So I tell him: “Not many, but some will.”

He nods his head knowingly. “Yeah,” he says.“There’s a lot of us — those who are here and those still coming.”