After Pittsburgh, Jose Antonio Vargas asks, ‘Who is an American?’

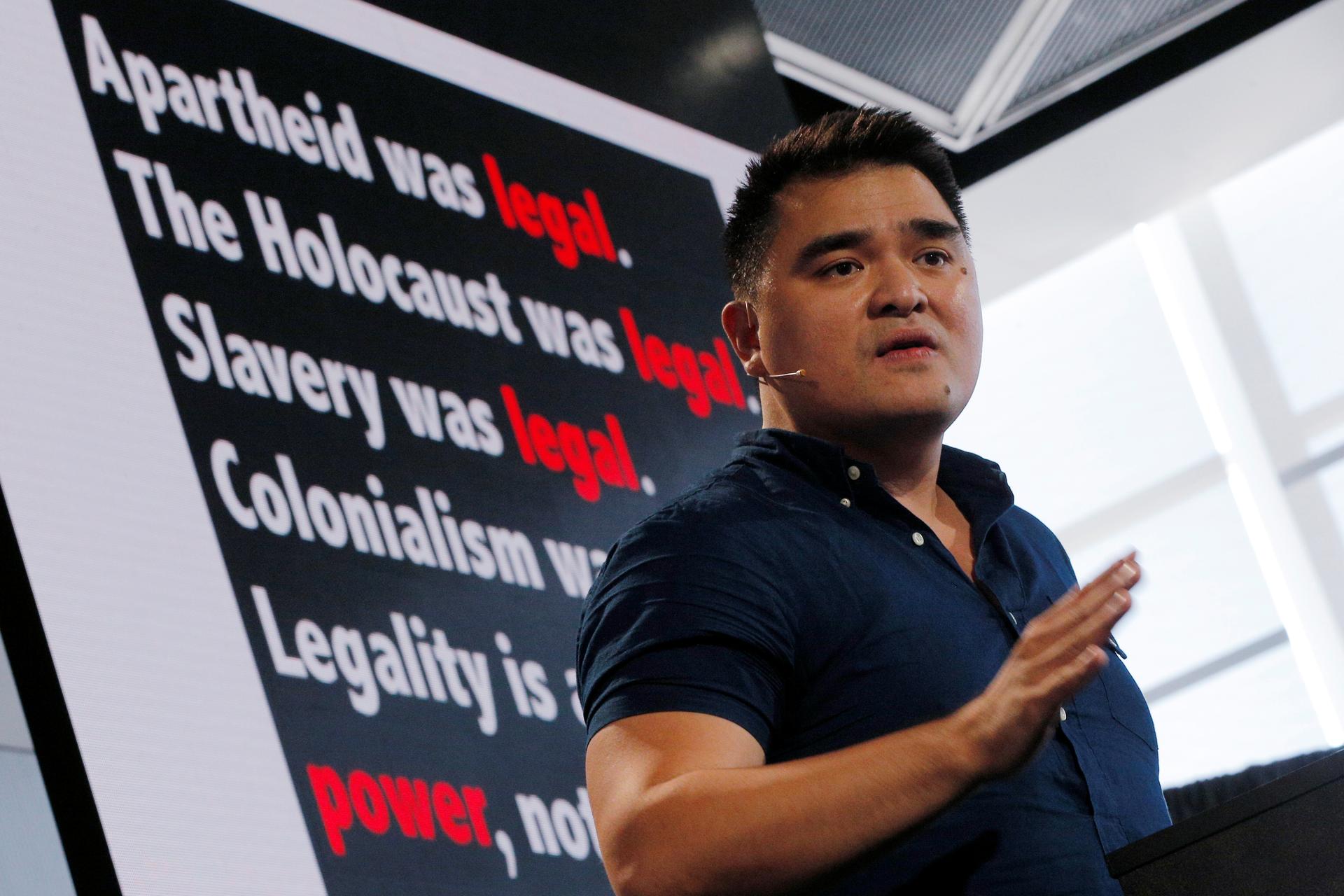

Pulitzer-prize winning journalist, founder of Define American and undocumented immigrant Jose Antonio Vargas speaks during “Defiance!” at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, US, July 21, 2017.

Jose Antonio Vargas is one of the most high-profile undocumented immigrants speaking out in the US today. The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist told The World about his new book, “Dear America, Notes of an Undocumented Citizen.”

After we spoke to Vargas, President Donald Trump told Axios that he plans to sign an executive order that would remove the right to citizenship for children of non-citizens and undocumented immigrants born on US soil.

We reached out to Vargas to ask what he thought of the potential end to birthright citizenship in the US.

“Is citizenship merely an act of birth?” he asked. “Or is it more than that? What are we really striving for as a country? What do we really want as a country? How do we see people beyond just labor and beyond what they contribute economically, but what they contribute as people, as human beings?

“We have to ask ourselves not only the question of citizenship but how do we as a country and as people define who an American is?”

A transcript of The World’s conversation with Vargas about his latest book and how it fits into public discourse is below.

Rupa Shenoy: So much has happened in the last couple of days. Has anything that has happened in particular made you reflect on your background?

I’ve been thinking a lot in the past 48 hours about all the Jewish Americans in my life. And as it happens, when I think about being an undocumented immigrant in this country and I think about the people who welcomed me into their lives, some of them are Jewish people.

And given the context of what happened in Pittsburgh and the fact that the gunman had a history of criticizing Jewish people being so welcoming of other immigrants … I just cannot stop thinking about that context.

Other immigrants like yourself?

Yeah. You know, when I got to this country in the early ’90s, I didn’t really know anything about Jewish people. I mean, I remember one of my biggest sources of confusion earlier on was like, “What is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?” I didn’t know anything about that and I didn’t know anything about Jews.

And especially when I got to a high school, there was the Greenstein Wade family. It was the first time I’d ever had a Jewish friend but I didn’t know what that meant either. Her name was Natalie Wade. A classmate then, I ended up meeting her mom, Gail, and Gail’s mom, Rita, and Rita’s husband, Eli. And then they kind of adopted me into their family.

And then when I got to the Washington Post, I was assigned a professional mentor and his name was Peter Perl. And he taught me the meaning of the word mensch. I didn’t know what that was. He got hired at the Washington Post in 1981 — the same year I was born. So he had been there for a while. He was the first and only adult at the Washington Post that I told I was here illegally. And he made a very crucial decision that basically saved my career.

To accept you coming out as undocumented?

Yeah, I came out to him. You know, I got hired at the Washington Post after right out of college, June 2004. By October, I was really paranoid. I just thought that someone was going to out me, someone was going to find out at some point. And I was so paranoid that I ended up deciding to tell someone, to out myself to someone, to see what I should do. And so I picked him [Peter] because he was so friendly to me. And I told him everything: the fake papers, everything I had to do to lie my way into a job at The Washington Post.

And I expected him to report me to the human resources department. Instead, Peter said, “You make so much more sense now. This is now our shared problem. Don’t tell anybody else. Just keep going.”

But then you did want to tell everyone else. So you write that piece but then the Washington Post spikes it.

Yeah, the Washington Post spiked it. And actually, I remember Peter and I, of course, we’re communicating throughout all of that. At the time he was still at the Washington Post and he was as perplexed and as frustrated as I was that the Washington Post ended up killing the piece. Marcus Brauchli was the editor-in-chief of the paper at the time. He just told me that he didn’t know what he didn’t know. I think … I had lied about my status and they’re probably wondering what else I was lying about. But Peter, through all of that, stood by me. And actually, now Peter is on the board of Define American which is the organization that I founded when I came out as undocumented.

So I’ve just been thinking a lot about Peter and Gail. And, you know, all those people who happen to be Jewish in my life who made no hesitation about welcoming me into their families.

In the book, you describe how you almost have two families. How did you navigate that?

Well, I think a lot of a lot of people who grew up in immigrant backgrounds can relate to this because there’s the dynamic at home in an immigrant household, that we’re told that we shouldn’t want too much. We should put our head down, don’t make too much noise. We’re here to just work. We’re not here to be visible, to be seen. And yet, I had this other family — that was mostly from my high school, Mountain View High School and then Peter Perl at the Washington Post — who just wanted me to succeed in all the ways I could succeed. So it was definitely conflicting, but also helpful.

I think if I didn’t have all those people in my life who told me to keep going and that these immigration laws didn’t make any sense at all, I’m not sure I would have had the career that I had. I’m not sure I would have allowed myself to be encouraged and to pursue what I wanted to do.

Why was that an important point to make, that American citizens helped you survive and thrive in this country?

That was not only an important point, but for me, a very central point to make. Because when we talk about undocumented people like me in this country, it’s almost as if we exist like islands unto ourselves. When the reality is, people like me in this country cannot be in this country working, living, surviving, thriving without all those US citizens who help us out at every juncture: at school, at work, at the church.

You know, you can’t separate those two … you can’t separate that kind of reality. And yet when we talk about immigration, especially illegal immigration, the role of US citizens are actually not much part of the conversation.

OK. Back to 2011, when you decided to go public with your status. Earlier, when you were talking about that, did you say that saved your career?

Well, the irony about all of this is that I thought the moment I came out as undocumented, my career will be over because I know how newsrooms work. Like, I’m supposed to be “objective.” I’m not supposed to air out who I am because that would impact the way other journalists see my work. Especially if you’re a person of color, or gay, or a woman. If you’re not a heterosexual white male, your identity is seen as some sort of an agenda, as a bias. And I knew that growing up. I’ve grown up in newsrooms my entire life and I’ve always had to make sure that people know that my work stands on its own.

I remember when I was at the Washington Post and I started writing about HIV AIDS, the AIDS epidemic in Washington, DC … an editor I really admired stopped by my desk one night and said, “Hey, you know, being an openly gay journalist writing about AIDS is not the way to get ahead in this newsroom.”

I was so taken aback by that comment. But I understood where he was coming from and what he was trying to say.

You were coming out at a time when the other so-called “Dreamers” were coming out for the first time. What followed was President Barack Obama taking executive action to protect “Dreamers.” Have you thought about how that moment and how your part in it led to what we’re experiencing today?

I think all of these moments build on top of one another. When I came out as undocumented, years before that, there had been many undocumented young people who had been coming out. What was different about my story was that I was a journalist. You know, I worked in newsrooms and I think a lot of my colleagues in journalism were just surprised that someone kind of made it in their own newsroom. Right?

All of a sudden, [we weren’t] just at school, in college. Or not just in the farm, harvesting crops, or not just a nanny babysitting kids — which is kind of how people usually think of people like us. I was in a newsroom — and I have to tell you I’ve heard from so many undocumented journalists of all different ages.

So that’s been really interesting. But for me, coming out was also a way to say that this is bigger than the Dream Act. You know, I was a “Dreamer” before there was a Dream Act. I was a dreamer before there was any language around it. We [undocumented immigrants] couldn’t find each other. There was no social media. There was no Google. So, I’m kind of from the older generation of dreamers.

Also: DACA Diaries, a series about the young people who call themselves dreamers

In the book, you write about something I actually hadn’t seen anyone talk about before, frankly. You write: “To some longtime activists and organizers, my arrival to their movement was too late and my story was too complicated.” And some have called your decision to go public with your undocumented status a “career move.” How do you react to that?

So I have to tell you, writing about all of that was so hard just because I didn’t want to make it seem like I was “complaining.” You know what I mean? I’m sure after reading the book you got a sense that I really wanted to write it in such a concise way — kind of make sense of everything that’s happened. But yeah, that whole idea that I did not fit the stereotype of what an undocumented person was supposed to be …

I remember early on I met a woman who had done such a spectacular job supporting undocumented students. And she told me that my story was problematic because I had broken all those laws and now I’m admitting to it and it didn’t fit the “faultless Dreamers.” Like, “It wasn’t their fault! It was their parent’s fault!” Right? My story was much more complicated. The narrative that I was trying to present wasn’t as “sympathetic.” And the fact that I had been so open about all the laws that I had to break — because look, if I can’t be honest about that, then what am I doing? I have to be honest from the very beginning about saying, “OK, these are the laws and I had to break them just so I could have a career. Just so I could survive. Just so I could pay taxes — because we do pay taxes. We do contribute.”

So that was really tough to do. And as a journalist, I didn’t really have any training in terms of how to deal with activists. You know, I wrote about activists I didn’t know. I wasn’t friends with them. So it was just it was very disorienting.

Do you think you represent undocumented people? Or can any one person represent [undocumented immigrants]? Because you say people call you “the most famous undocumented person” in the end of the book.

And I don’t even know what that means! I have no idea what that means … There is no one story. There is no singular narrative. I would argue that we are where we are right now because we’ve fallen into that idea that there’s one narrative, and one story. And the story is “it’s the border, it’s the wall. They’re taking over. They’re not contributing. They really didn’t want to be here.”

That whole narrative that is so just insipid and ugly and untrue, it elected a president.

So you have become an activist. Is that fair to say?

You know, I’ve gotten to this point now where I try not to be bothered by how people define what I do. As far as I’m concerned, I write, I report, I make films. That’s what I do. Everybody else can call me what they want to call me. And in many ways, I think what people describe my work as says more about them than it does about me.

And part of what you do is go on — you mentioned Bill O’Reilly — other Fox programs. I guess the question is, how do you accomplish what you hope to accomplish during those appearances?

I just remember the that first time I ever really saw the country — meaning, Wisconsin, Iowa, Ohio — was in the 2008 campaign. I was at the Washington Post. I was a political reporter. I was sent because I was one of the few people on the political team that wasn’t married. [Laughs] So, they kept sending me to places.

So they sent me to Iowa for the whole month. Iowa has 99 counties. I’ve been to every single one of them. I know every single Starbucks in the great state of Iowa. And that was the first time that I really spent considerable time in a place that wasn’t urban or it wasn’t “liberal.”

And it was a real wake-up call. For me, that was when this idea that we don’t live in a country where there’s a shared narrative. Like there are countless numbers of Americans whose reality is shaped by Fox News, Breitbart, Drudge, Daily Caller. There’s an entire media ecosystem that exists that is, like, parallel to the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Associated Press, the BBC, NPR.

So that was a real wake-up call. And then I learned that it’s a mistake to just discount people who watch Fox News. Now mind you, I could I really could care less about Tucker Carlson or Ann Coulter. I mean, I think they’re fantastic actors. Ann Coulter has been saying what she’s been saying since I was in high school, in middle school. She’s been very, very consistent. But I think for them, it’s like a role to play. So when I go on Fox News, I don’t go on there to talk to Tucker Carlson. I go in there to talk to the people who watch Tucker Carlson. And who — whether or not they like it, or whether or not I like it — share the same country. And I can’t afford to just “not want to talk to them.”

One thing I wanted to touch on — we’re looking at this “caravan” coming up from Central America. And the President saying, “We’re not going to let them in,” and things like that. One thing you did in your book is explain the history — up to the point of your own name and how you ended up being part of a family that wanted to come to the States — and how it was influenced by the West. Can you tell that story?

Well, first of all, thank you so much for noticing that. That was a very important detail for me to put in the book. I think that when we explain why people moved to America or why migrants are moving to Europe from Africa or from Southeast Asia or whatever, I think we have a very simplistic way of doing it in America. You know, people assume that migrants know about the Statue of Liberty or the American dream.

I didn’t know anything about that. All I knew was when I was a kid … America was Coke. It was Nike. It was Spam. It was the Hershey’s Kisses. It was all the stuff that my grandparents in America, who are naturalized citizens, sent to the Philippines to my mother and I. So American capitalism was very present since I was a kid. McDonald’s was there, right?

And I think we don’t [evaluate] what American foreign policy, in American economic policy, in addition to the wars that we fight, what those reasons have to do with why people move. You know, I was in North Carolina a few years ago and I was doing this Tea Party event, actually. And I ended up saying that there are 4 million Filipinos in America. We’re the third largest immigrant group: Mexicans, Chinese and Filipinos.

And this white man, elderly white man got up and he said, “Why are there so many of you here?”

And I said, “Well you know, sir, we are here because you were there. The Spanish American War? My name is a product of Spanish colonialism. Jose Antonio Vargas but ‘Jose’ doesn’t have an accent on the ‘e’ because when the Americans took over after the Spanish American War, their typewriters didn’t have accent marks. So my name is a marriage of Spanish colonialism and American imperialism.”

Yes, because I’ve just been prepared. You know, we live in the cell phone era now and so we don’t memorize people’s numbers anymore. So I had to memorize my lawyer’s number because if I get arrested at any point, in an airport or wherever, I get one phone call. And I’ve got to go call the lawyer. All right, so I’m prepared. The bond letters are written so if they detained me, I have letters that I’ve collected from my high school principal, people who have known me since I was a kid, testifying that I won’t be a flight risk. So I’m prepared for whatever that process is.

I’ve been detained already. I know what that’s like. Although … the last time I got detained was during the Obama era. It was only for eight hours. I have a feeling that the next time I get detained it’s not going to be for eight hours. It’s going to be longer than that.

More: Vargas was detained in 2014 in Texas, released and notified to appear in court.

But do you feel like you can talk about that? Because there are children in detention going through worse things …

God. Absolutely. And I got out, right? I got out after eight hours. There was breaking news on CNN. And that’s the thing, like owning up to the fact that I am privileged right now. Undocumented people don’t go publish books and talk to the BBC. And yet, that’s what I’m doing.

My goal in the book was to be as honest about myself and my place in this very complicated reality. And the book, for me, is kind of a statement of independence. Independence from the immigrant activists who may not understand why I do what I do. Like, why Define American — the organization that I founded — we’re not saying, “Go pass immigration reform.” I want immigration reform to pass. But just because we give people pieces of papers and pass laws doesn’t mean that all of a sudden 11 million people are going to be welcomed in American society. So our strategy from the very beginning has been very different from the rest of the immigrant rights movement.

This may sound really trite, but I never had therapy before. I’ve been running since I was 16 years old, when I found out I had been living here illegally. I’d been running ever since and this book was really the first time I sat down and tried to make sense of what happened. Like, why I am the way that I am.

We started out talking about the people who helped you become someone and go places where people wouldn’t think you’d be able to go. Like the Washington Post newsroom. And now we have this synagogue that was attacked. People who did help refugees. Do you think people are still helping young people like you? American citizens are still playing that role? Do you think that’s going to change?

Absolutely. It’s out. It’s happening. They’re helping, I know this. I know this because they follow me on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram and they send me messages. I know this because if it weren’t for the generosity of all these people, including Jews who know a lot about homeland and the search for a home … if it wasn’t for that generosity I don’t really know why the sky hasn’t fallen.

You know at a time like this, I have to believe in love. I have to believe in the generosity of people. I have to believe that we don’t struggle alone. I would argue that after this horrific, horrific tragedy I bet you that more people are going to be more willing to help.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Next: How immigrant rights activists fought — and won — a battle against unjust laws and deportations