In Canada, some doctors are prescribing heroin to treat heroin addiction

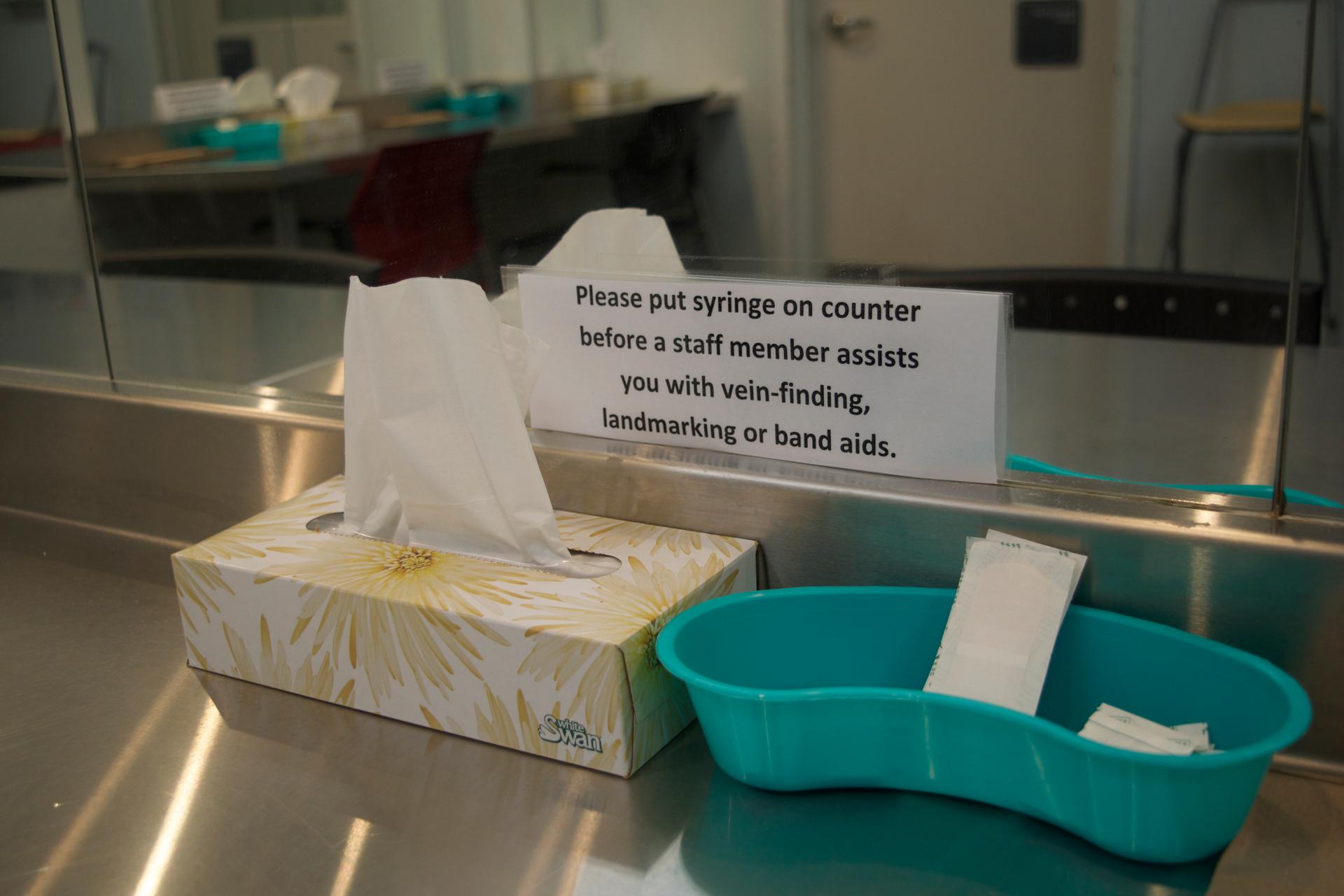

At Providence Health Care’s Crosstown Clinic, patients received a measured dose of either hydromorphone or diacetylmorphine at a window in this room. Then they sit in here and inject it, under the supervision of a nurse.

Every day, Brent Olson travels some 20 minutes by train into Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighborhood. He has a degenerative hip disorder and uses a walker to get around. But there’s no way he’d miss this clinic appointment.

“The best decision I’ve ever made in my life was coming here,” Olson said. “I wouldn’t be sitting here talking with you. I’d be dead.”

He makes his way past the double security entrances, checks in and heads to a room in the back of the Providence Crosstown Clinic. There, a health worker hands him a syringe through a window. Then he sits at a long, metal table against a wall that’s lined with mirrors. He finds a vein on the inside of his arm and injects the drugs while a nurse stands nearby.

Related: In Vancouver, people who use drugs are supervising injections and reversing overdoses

“I put a cap on the lid, return it and that’s the name of that show,” Olson said after a recent injection.

Olson, who’s 55, is one of several dozen patients at Crosstown Clinic. He and the others come in three times every day to receive a closely-monitored dose of diacetylmorphine, otherwise known as pharmaceutical-grade heroin.

Related: Is acupuncture a viable alternative to opioids for patients in pain?

Like the US, Canada has been wrestling with a growing drug crisis. Deaths from overdoses in Canada have reached unprecedented levels, up to nearly 4,000 last year. In response, the government has pledged more resources for addiction services.

Primary treatments involve maintenance medications like methadone and newer ones like suboxone. Still, not everyone responds to these medications, whether because of continued cravings or harsh side effects. That’s prompting a small but growing number of doctors to take another approach: prescribing heroin to treat opioid use disorder.

Related: US health care companies begin exploring blockchain technologies

“This is just one treatment for a chronic, manageable illness — just like diabetes or high blood pressure,” said Scott MacDonald, Crosstown Clinic’s lead doctor. “[Prescription heroin] is a life saving intervention for a small number of folks with a chronic, manageable illness that haven’t responded to anything else.”

When patients no longer have to spend their time and energy on getting their next fix, MacDonald adds, they can tend to other parts of their life, like housing and employment, and the underlying issues driving their addiction.

For Olson, who’s been a patient at Crosstown for about five years, drugs have consumed most his life. Growing up, he had professional hockey dreams. They imploded when he wrecked his ankle during practice.

“It was a real blow,” Olson said. “I did turn to drugs.”

He describes much of his life after as a blur, spending years shoplifting, going to jail and doing whatever he had to do to feed his heroin addiction. He tried traditional treatment — taking methadone every day — but says the side effects were rough and the treatment didn’t work for him. So, back on street drugs, he knew he was risking his life. He never knew exactly what he was getting — whether that heroin fix he so desperately sought would be his last.

It’s this sort of situation that prompted MacDonald’s move to Crosstown.

Related: As opioids land more women in prison, Ohio finds alternative treatments

MacDonald previously worked at a clinic nearby, providing traditional treatments, like methadone, for opioid use disorder. Methadone and buprenorphine are standard medications, taken by mouth. They work in different ways to relieve cravings for heroin and suppress withdrawal symptoms. But not everyone benefits.

MacDonald points to findings that about one in 10 people don’t respond to conventional addiction treatments. He’d seen lots of people choose street drugs instead, with unstable lives and the persistent risk of overdose.

With prescription heroin, his patients aren’t dying of overdoses. They’re rarely overdosing at all, he says.

Turns out, heroin as a form of replacement therapy is not actually a new idea.

The United Kingdom has used prescription heroin for nearly a century as an option for drug users who’ve repeatedly failed with traditional treatments. Several other European countries run their own programs.

In Canada, Crosstown got its start as a pilot project in 2005, becoming the first place in North America to prescribe heroin. It imports the drug from Switzerland. The dropout rates were much lower for those being treated with heroin, compared to the average dropout rate for those treated with methadone. Patients receiving prescription heroin were also much less likely to turn to street drugs, compared to those taking methadone.

Treating a substance use disorder with the very drug that people are addicted to may seem like a radical idea, but it’s catching on in Canada. That’s, in part, because of more recent research at Crosstown on the use of injectable hydromorphone and prescription heroin — as well as an increasingly contaminated street drug supply.

“Now, everything’s changed,” said Mark Tyndall, director of British Columbia’s Centre for Disease Control.

Tyndall, a longtime doctor in the neighborhood near Crosstown Clinic, has spent his career working on ways to reduce the harms of drug use. But even with these efforts, he says a deadly narcotic called fentanyl has upped the stakes, making its way into the illicit drug supply fueling a surge in fatal overdoses. British Columbia experienced about 500 overdose deaths in 2015. In 2016, the number rose to about 900, and then to 1400 by 2017.

“If it’s at the point where every flop of drugs that people are buying could have a high amount of fentanyl and a potent, deadly supply of fentanyl, I don’t know what harm reduction service we could do to fight that,” Tyndall said. “We need to get people the opportunity to get a safer supply of drugs.”

The Canadian government has eased the regulatory burden on Crosstown Clinic. The regional health agency has also been pushing for expanded use of prescription heroin, by working on ways to make it easier to access, backing new clinical guidelines and supporting more doctor trainings.

Related: Thamkrabok Monastery has a reputation for its cold-turkey detox

Tyndall recently started working at a new clinic just outside Vancouver that offers injectable hydromorphone, which is easier to get. He’s also getting ready to launch a government-funded pilot that would give registered patients access to the drugs outside a clinic.

But using heroin as a way to treat addiction is troubling to some people, like Jeremy Devine.

“Prescription heroin is numbing pain in trauma. It’s not getting to the root cause,” said Devine, a doctor working outside Toronto and beginning to specialize in psychiatry.

Related: A scientist who finds pharmaceutical promise in the venom of cone snails

Growing up, he says he watched a close family member struggle with drugs. To him, prescription heroin reduces what it means to quit.

The policy has faced opposition from Canada’s opposition party, too.

“Keeping somebody safely addicted to drugs is not my definition of success, nor my party’s,” said Marilyn Gladu, a member of the Canadian parliament representing part of Ontario and the conservative party’s shadow minister of health. “We would really prefer to see people not get on drugs in the first place, or see them treated to get off drugs.”

When her party was in power in 2013, it blocked Crosstown’s prescription heroin orders. The clinic challenged the decision, and when the liberal party took control of parliament, the government restored its support.

In recent years, the Canadian government has loosened restrictions on who can provide oral addiction treatments, as well as prescription heroin, and where. Health leaders say it’s vital to have a range of options for people, and British Columbia’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions is now putting about $40 million a year into recovery and treatment services. But, despite that, the drug crisis has created what might seem like a surprising advocate for prescription heroin: police.

“I think it would prevent people from having to go out and commit crime in order to support their habit, or spending every dime that they earn to, you know, maintain their opioid addiction,” said Bill Spearn, a member of the Vancouver Police Department for 22 years.

Spearn says his unit makes plenty of drug busts, but fentanyl is cheap and widespread. He sees drug addiction as a health issue and prescription heroin as one of many types of treatment for it.

He says it could help keep people out the criminal justice system.

British Columbia now has at least five places that offer injectable hydromorphone or prescription heroin, according to BC’s Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. The number of newly enrolled patients is still tiny compared to the tens of thousands of people injecting illegal drugs. Crosstown’s waitlist is about 400 people. A handful of new clinics in other parts of Canada, including Alberta and Toronto, are preparing to open.

This reporting was supported by WHYY’s The Pulse.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?