In Vancouver, people who use drugs are supervising injections and reversing overdoses

Pop-up injection site coordinator Sarah Blyth with an overdose naloxone kit in vancouver’s Downtown Eastside Jan. 30, 2018. The former pop-up safe injection site now has a permanent home next door to the former temporary site.

Hundreds of times each day, people settle into individual mirrored booths in a building in the heart of the Downtown Eastside neighborhood of Vancouver, British Columbia. They unpack the drugs they’ve brought and then do their thing, prepping, then injecting. But here, they shoot up under the watch of a nurse. Clean needles and naloxone are within easy reach.

Mat Savage credits the place with saving his life.

“I don’t even remember finishing the shot, I just remember bringing it up, starting to do it,” Savage said, describing an overdose from about four years ago.

An overdose can happen when too much of a drug like heroin takes over receptors in the brain. It slows down vital functions like breathing, turning a powerful high into a potentially fatal one.

Savage, who’s 44 now, says the nurse at Insite immediately responded, giving him oxygen and naloxone. The medication blocks the heroin and can reverse an overdose on the spot.

After years of heated debates, rising overdose and HIV infection rates, and mounting pressure from people who use drugs themselves, the Canadian government opened Insite in 2003, making it the first publicly sanctioned injection facility in all of North America. It has on-site health services, is in a part of Vancouver that has long been a nexus for illegal drug use, and has been the subject of research — a required condition for operating.

To people like Savage, the opening of Insite was a powerful alternative to him and others using alone in alleys or parks, fearing arrest and risking a fatal overdose.

“If we could do away with drugs, that would be great but that’s not a reality,” said Savage, adding that some people are not able or don’t want to stop using. “The reality is drugs are here, people are going to use them.”

Fast forward to 2018: Despite having overseen some 3.5 million injections and reversing thousands of overdoses since opening 15 years ago, Insite alone could not hold off the deadly impact of an influx of more potent drugs like fentanyl. The narcotics have made their way into the illicit drug supply throughout North America, fueling an unprecedented number of overdose deaths in the surrounding community and continent.

In Vancouver alone, overdose deaths have shot up 80 percent just in 2016. The region continues to wrestle with the highest overdose death rates in all of Canada, with fentanyl detected in a majority of cases.

The escalating situation in Canada has activists like Tina Shaw pushing supervised injection into new spaces outside the walls of Insite, which until recently was the only option for supervised injection in Vancouver.

‘We weren’t going to stand by and let people keep dying’

Shaw is a petite redhead with a big presence who for years battled a cocaine addiction. She says she knew she had to do something when people started dying in record numbers.

“Paramedics were so overworked it would take between 12 and 25 minutes to show up for an overdose call [and] 12 and 25 minutes is too long,” Shaw said. “They’re gone.”

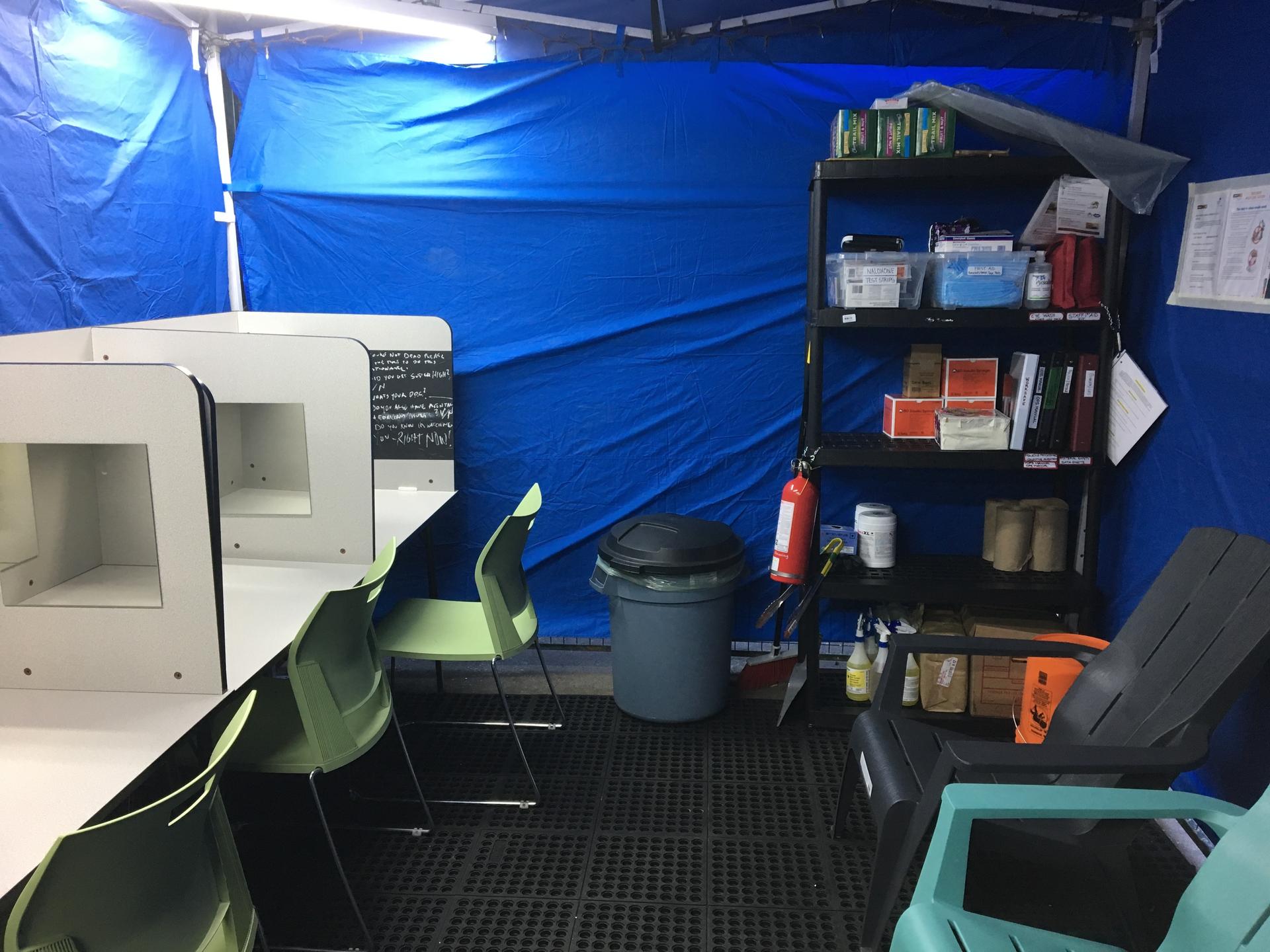

She and other activists decided to set up their own kind of injection sites — often referred to as overdose prevention sites — as people started dying in greater numbers. At first, they put up medical tents in the alleys, right where people were overdosing, standing watch with naloxone and breathing masks at the ready.

“I’ve lost so many people I care about because of fentanyl,” said Shaw. “We weren’t going to stand by and let people keep dying.”

At the time when they first started in late 2016, their tents were illegal. But when public health officials visited, they did not shut them down. Instead, they declared a public health emergency and funded them.

Now, there are more than 40 of these more informal sites across the region, according to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction. They’re in apartment buildings, homeless shelters and even in some rural communities. The local health authority spends nearly $1.8 million a year on these more informal sites, and $33 million on other addiction and recovery services.

A couple semi-outdoor sites have opened, where people can smoke their drugs too. Maps of the locations are advertised on several public health sites and the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs (CAPUD) has even created a manual for how to set up the tents.

‘If there’s a way I can give back just ask and I’ll do it’

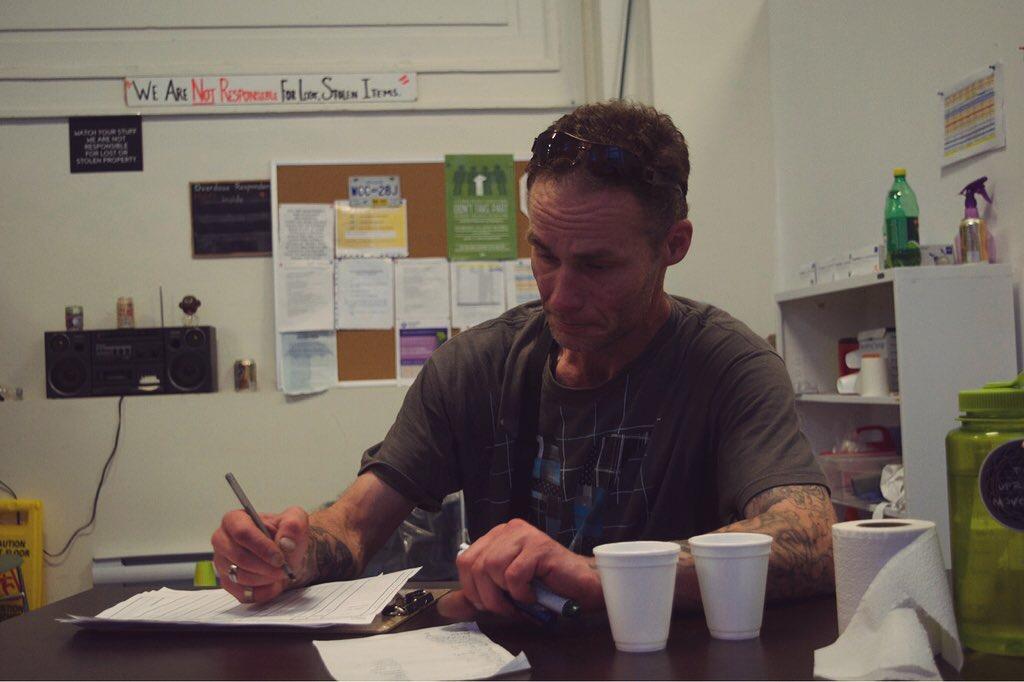

Shaw has been most involved in the Molson Overdose Prevention Site located at the Molson Bank Building in downtown Vancouver. The entrance is in an alley just a few blocks from Insite but there’s a big difference: nurses don’t run the place. Peers like Daniel Beaverstock do.

“We’re also in active use, most of us,” Beaverstock said. That means there’s a greater understanding between the person using drugs and the person watching over them. “That’s why we’re peers, right?”

Beaverstock often sits at a table by the door, helping people sign in. As part of the intake process, people give a nickname and indicate what kind of drug they’re using. Social workers are on hand, but lots of the staff also actively use drugs and are trained to respond to overdoses. The local health authority, Vancouver Coastal Health, sponsors the trainings and certifies people, both to respond to overdoses and to train others. But it also means that when Beaverstock Is not on the clock, he injects his drugs there, too.

“Both to save my life and how can I encourage people to come use here if I’m out in the streets using myself?” he said.

Beaverstock credits places like these for saving his life dozens of times.

“I said, ‘If there’s a way I can give back just ask and I’ll do it.’”

The main injection room of the Molson site is wide, with eight rectangular metal tables, spaciously set up along the walls. It’s a lot more low key compared to Insite. People can share booths and even help one another inject.

Stephanie Peterson is a regular at Molson, sitting in booth No. 3 on a recent spring evening, prepping her drugs.

“I’m in tears every day because of dope,” Peterson said, adding that she’s been addicted to heroin since she was a teen. “I still use it every day but it’s not like it’s easy to put the dope down. If it was, I’d put it down.”

Fentanyl, she says, has upped the stakes.

“I don’t think people realize how dangerous this whole fentanyl thing is,” she said, as she prepared an injection. “If we didn’t come here, there’d be so many more deaths. So many more deaths.”

‘They die when they use alone and they’re not feeling like they can tell anybody’

Since these informal sites started popping up two years ago, they’ve reported more than 130,000 visits and have reversed more than 1,000 overdoses. The local police are supportive too.

“They prevent overdose deaths and are not a law enforcement issue,” said Bill Spearn, a longtime inspector with the Vancouver Police Department. “I mean, we just want to keep people alive long enough to get them into treatment.”

And the regional coroner’s office at one point estimated that without a response that includes supervised injection, fatal overdoses in Vancouver could be three times as high.

The approach is gaining support in other parts of the country, with more sites opening. But it does have critics.

“What we’re doing now is trying to put a band-aid on the symptoms of what’s happening without ever getting to a more meaningful long-term outcome,” said Tom Stamatakis, president of the Canadian Police Association.

Stamatakis says with such a tainted drug supply, the focus should be on getting people into treatment programs, which can have waiting lists. Ontario’s new conservative premier, Doug Ford, also wants more investment in treatment and recently placed a moratorium on new injection sites in that region.

In the US, where at least a dozen cities — from San Francisco to New York, Philadelphia and Seattle — are considering supervised injection, the deputy attorney general Rod Rosenstein has slammed the idea, pledging to crack down on any attempts, and is instead pushing for more law enforcement.

For Vancouver leaders like Mary Clay Zac, one of the city’s policy directors, supervised injection is part of a smart public health strategy to deal with the drug crisis. No one has died at a safe consumption site, she said.

“One of the biggest problems, though, that we’re still faced with, is that people who use drugs, they die when they use alone and they’re not feeling like they can tell anybody: a neighbor, a friend, their family, to watch out for them,” she said.

To Zac and other officials, the benefits of supervised injection also include preventing costly infections and easing the burden on hospitals and law enforcement.

For Stephanie Peterson, a regular at the Molson, these more informal sites have an added draw: With peers so involved, she doesn’t fear being judged when she comes in to use, whether she’s having a good day or a bad one.

“It’s my safe house, basically. It’s my safe zone,” she said. “Outside these walls, anything can happen but inside no one can touch me.”

This spring, an even more potent batch of fentanyl made its way into the drug supply. Canada has experienced some of its worst spikes yet in fatal overdoses.

“The latest data suggest the crisis is not abating,” a government advisory panel said on Sept. 18.

An average of four people a day are dying of overdoses in British Columbia as of July, authorities said. Recently, a big business association in Vancouver asked for an informal site to be opened in their upscale district, to prevent overdoses in store bathrooms.

Mat Savage, who recalled overdosing at Insite years ago, now works at a site that opened in May right next to a large hospital in Vancouver. It marks the first of these more informal sites to be located outside the Downtown Eastside neighborhood.

The city plans to open at least two more sites by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, where the premier has put a temporary ban on new injection sites, a group has set up their own one in an outdoor park.

This reporting was supported by WHYY’s The Pulse. A previous version of this story misidentified the title of Doug Ford.