When it comes to family separation, healing can take decades

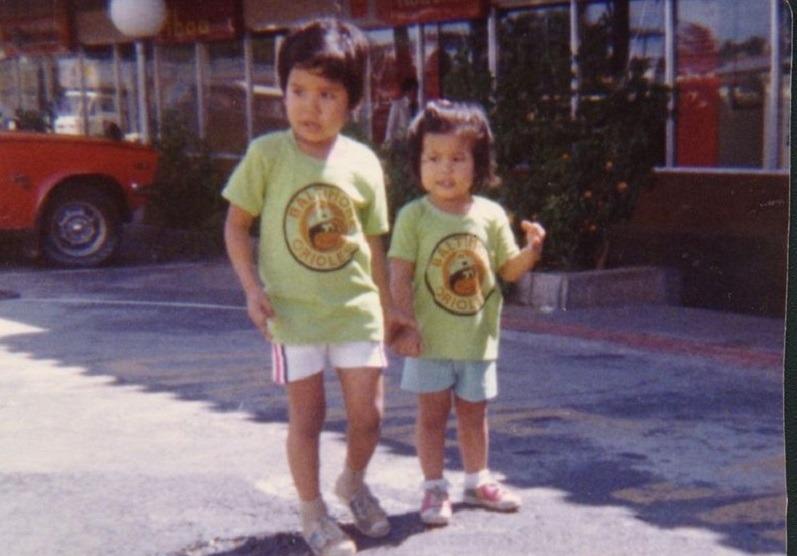

Glady Lee and her brother in the Philippines in the 1970s.

Back in the 1970s, long-distance phone calls were expensive. So the Guinto family, separated by the Pacific Ocean, used cassette tapes to stay connected.

In the Philippines, Glady Lee remembers her grandparents holding out a tape recorder to say a message to her parents living in San Francisco.

“‘Glady, come here. It’s time for you to say hi to your mom and your dad. Tell them what it’s like here. Do you want them to bring you anything from the States?'” Lee remembers.

When Lee was 2 years old, her mom, Nella Guinto, got a visa to go to the US as a nurse. Her husband also got a work visa. The idea was to bring their two kids as soon as they could.

After a long hospital shift, Guinto couldn’t come home and kiss her kids. But she could pick up a tape recorder to send a clip of her voice to her children back in Quezon City. “Have you been good? Have you been playing?” Guinto would say.

Today, mother and daughter are going through some of those cassette tapes. Guinto plugs in an old boombox, and she slips in a tape labeled “1978.”

Related: ‘We’ve been there’: Native Americans remember their own family separations

On it, Lee is speaking Tagalog. She’s 4.

This tape is from a few months after she and her brother finally got to the US. She’s telling her grandparents in the Philippines that she’s going to kindergarten soon, and the family is sharing a one-bedroom apartment.

And then there’s the tape Lee’s grandparents sent back: They’re promising to kill plenty of chickens, so they can feast next time the children visit.

So many of the tapes Lee and her mom find are broken. Perhaps the sounds from that critical time apart have been erased. But not in Lee’s mind. It’s all still vivid, even at age 44.

“We weren’t able to go backward and talk about being apart from each other,” Lee says.

So far, she has talked about the painful memories only with other people — not her mom and dad. That’s because everyone in the Philippines told her she wasn’t supposed to be sad. Her parents had made it to America.

“The US was always the place that almost every Filipino wanted to go. That was the dream,” Lee says. “And so the dream was happening for my family.”

Related: A family tries to immigrate to the US, but first, they must live separate lives

But that’s not how it felt to a 2-year-old.

“I was sad every day when she was gone and I just didn’t know who to express that to, because everyone around me was saying that you should be happy, that you were going to join your mom soon,” Lee says, tearing up. “All the feelings that we had about being separated, it’s almost like it was swept under the rug.”

Once Lee made it to California, and she was in elementary school, she saw a movie that reopened some of those wounds.

“You know that scene in ‘Dumbo’ where Dumbo’s mom is in the little jail cell, and she reaches over and grabs Dumbo with her trunk through the bars? It felt like I was Dumbo.”

The pain came back again this summer, when she heard the stories of children separated from their parents at the border.

Lee says the worst news story for her was about a father who called his son in detention.

“Don’t you love me? Why did you leave me?” the boy asks his father. “Why can’t we be together?”

For Lee, this was too familiar. “When you’re a child, those are the only things that you really care about,” she says.

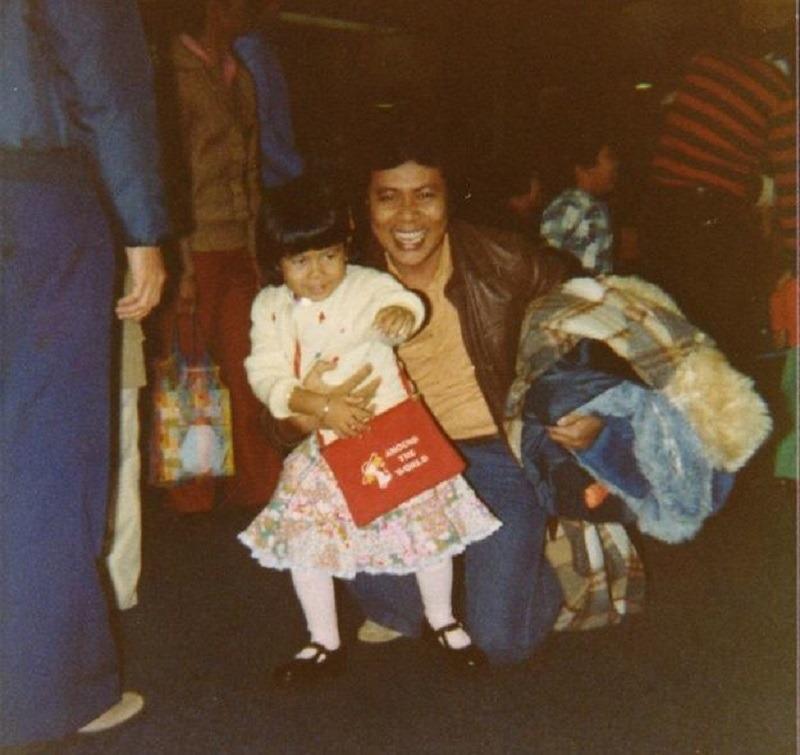

Lee was reunited with her parents when she was 4 and remembers what it was like waiting for her dad at the San Francisco airport.

“’Where is he? That one? Is that my dad?’” Lee remembers. “And then when I see him finally, I’m like, ‘Oh, that’s totally my dad because he’s the one that’s hugging me right now. And he loves me.’”

But after nearly two years apart, it wasn’t just joyful hugs and kisses. Lee still has scars. And hearing those kids crying on the news, she knows it will be the same for them.

“I definitely think that there’s a mental health component. And so it almost feels like it’s affected almost every really close relationship that I’ve had with people,” Lee says.

Or even casual relationships, like the one with her children’s violin teacher, who’s moving away.

“The idea of her leaving just kind of sets me off,” she says. “People leaving is very traumatic.”

Lee has two boys of her own now, ages 10 and 14. When they were younger, she stayed home. She wanted to be there during their toddler years, because her mom and dad couldn’t be there for hers.

She’s grateful her parents got her to California, where she could make that choice. “They put us through college and we have jobs. So that’s how it’s come full circle, I guess.”

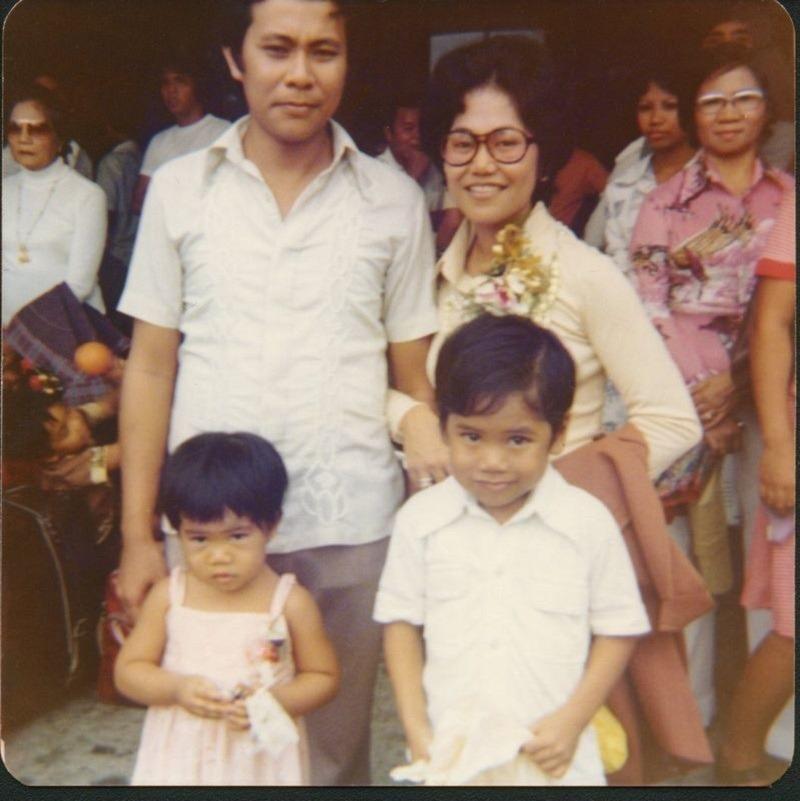

At her parents’ house in Vallejo, Lee joins them on the couch to look at photo albums. Some are so old that they have to unstick the brittle plastic pages to see them.

In one photo from 1976, everyone’s dressed up. Lee is 2, wearing a pink sundress. She looks sad and confused.

Lee asks her mom, “I might just be making that up, but it looks to me like you were crying?”

Her mom ignores the question. It’s only when the reporter presses her that she opens up.

“I guess it’s like a mixed feeling because when I was young, I really wanted to be a registered nurse and go to America,” Guinto says. “But I didn’t really completely feel that the separation will be that bad. And so I realized I had been crying and really missed them. Even leaving them to the grandparents, it’s so heartbreaking.”

Then her dad reveals something huge. Something Lee never knew before.

He and his wife didn’t choose to leave their kids behind in the Philippines. They had to. They couldn’t get them a visa.

“We applied all at the same time, but the consul took them off, the two kids, because the consulate said to establish ourselves here first,” he says.

They didn’t want to leave their kids, but it was a sacrifice they had to make to get to California.

“It was so hard. I could still cry,” Guinto says. She puts a hand on Lee’s back, then chokes up and hugs her.

But Lee remains stiff.

She’s still protecting her parents from her pain.

Later, Lee says she realized something new when she saw her mom finally cry about the separation. Guinto felt guilty about the little girl she had to leave behind.