‘We’ve been there’: Native Americans remember their own family separations

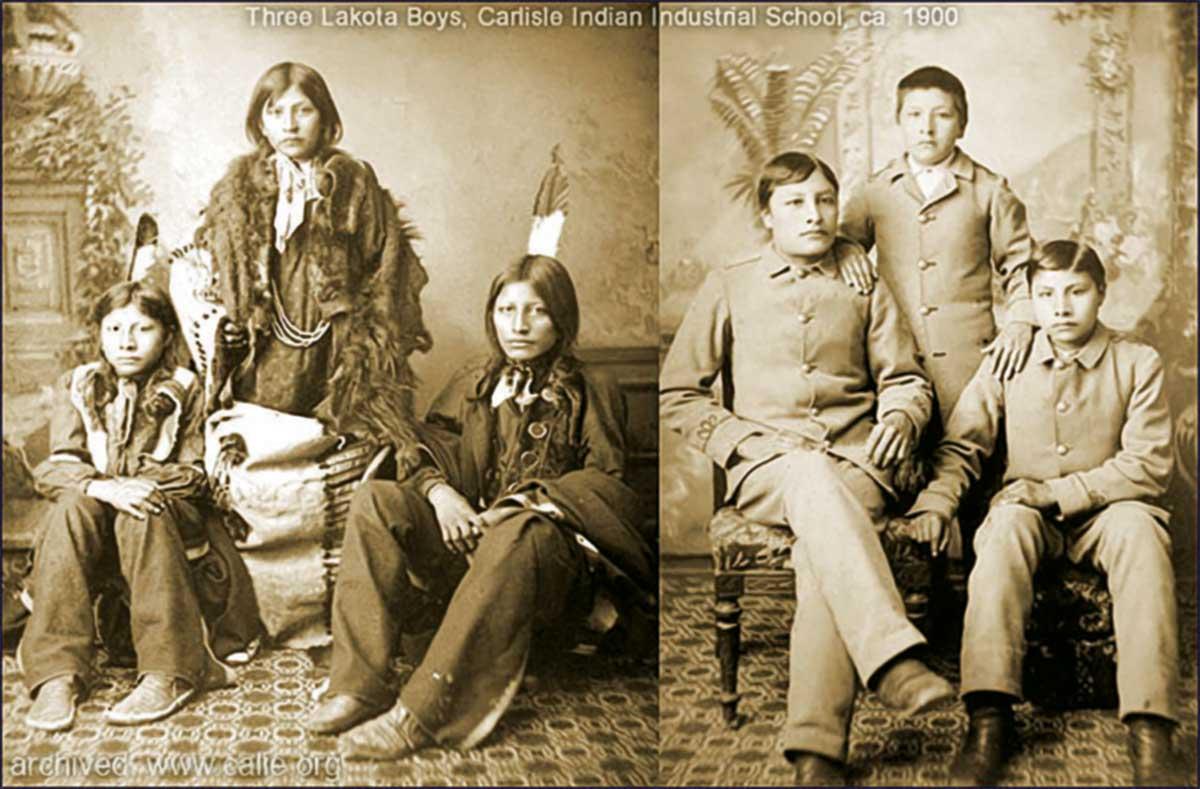

Wounded Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear and Timber Yellow Robe before and after their Pennsylvania boarding school gave them “proper” clothes and haircuts.

Many people in the United States have reacted to the separation of families at the border with sadness, protests, donations and a lawsuit against the federal government. But for some, the story feels especially personal, and familiar.

“My first reaction was, ‘Oh my God, this is what my mother went through,'” says Connie Reitman, who lives in Sacramento, California, but grew up on a Pomo Indian rancheria in the northern part of the state.

Related: This Indigenous tribe in Colombia is run solely by women

“It’s not a new story, unfortunately,” Reitman says. It’s a story her mother told her; a story she told her own children and her grandchildren.

She didn’t hear it all at once. Her mother doled out details gingerly as Reitman was growing up, weighing how much her children were ready for. It took years to tell them.

Related: Indian Country remembers the trauma of children taken from their parents

“All of us would lay in the bed and she would be sewing and she’d tell us about things that happened to her in the boarding school,” Reitman says.

Her mother was referring to a boarding school for American Indian kids set up by the federal government in the late 1800s. At first she shared positive memories about the place — she talked about learning to sew and cook at the school.

Related: On the 150th anniversary of the Navajo Treaty, young Navajo grapple with their traumatic history

As Reitman got older, the story got darker. “I was like probably about 11 or 12 the first time we heard the part about when she was taken from the family.”

One day in the mid-1920s, when Reitman’s mother was about 5 years old, there was a knock on the door.

“It was a federal official that said that my mother had to go to school,” Reitman says.

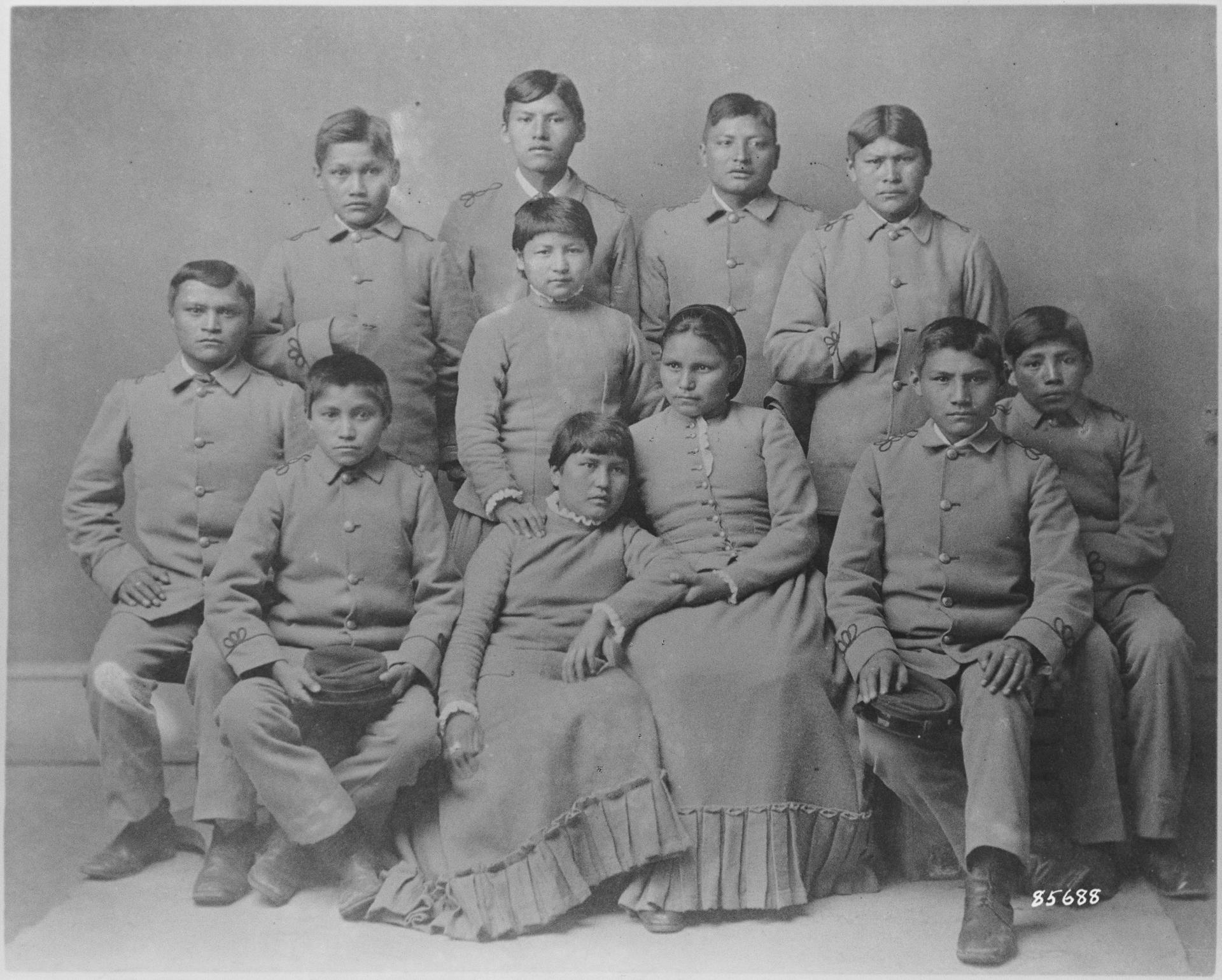

Until the mid-1930s, it was federal policy to assimilate Native Americans by eradicating tribal culture through a boarding school system. “The white man had concluded that the only way to save Indians was to destroy them, that the last great Indian war should be waged against the children,” writes David Wallace Adams in “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience.”

Related: The violent collectors who gathered Indigenous artifacts for the Queensland Museum

There were 25 such schools in the United States, including three in California. Federal officials forced parents to release a certain number of children from each reservation.

Reitman’s family has never known why her mother was taken while other kids weren’t.

“Not very much was able to be said or done,” Reitman says. “She was just taken.”

Taken from her home to Stewart Indian School near Carson City, Nevada, more than 200 miles away.

“So my grandmother and my grandfather didn’t know where my mom was and they didn’t really know how to get ahold of her,” Reitman says.

Related: Can First Nations Court stop Indigenous women from ending up in prison?

Tens of thousands of kids were put in boarding schools, where a report commissioned by the government described hunger, overcrowding, disease and hard labor.

“At the school, her hair was cut. She was not allowed to talk her language. There was a lot of hunger and abuse.”

Reitman says her mother would get punished for crying because she wanted to go home, “but all she could think of was to get home.”

Reitman’s mother contracted tuberculosis and was sent to a hospital in San Francisco. After two years of treatment, she was allowed to go home. She was 14.

“When my mother came home she was not really accepted — ever really accepted — back into the tribal community because she’d been gone for so long,” Reitman says.

She’d been away about nine years.

The trauma of these experiences shaped her life, but it also shaped Reitman’s. She says that’s why seeing children separated from their parents at the US-Mexico border today feels so personal to her.

It’s why American Indian leaders have come forward to condemn the actions.

“It’s a good opportunity for America to be able to relate to what happened to us as tribal people,” Reitman says.

Reitman is almost 70. She runs the Inter-Tribal Council of California and has dedicated her life to working with tribal communities around this legacy of trauma. She says we can’t heal if we don’t remember our history.

“We don’t want this to keep happening to the families, to children, because we’ve been there, done that, and we know what it’s like,” Reitman says. “These wounds are generational, multigenerational. That’s why we have to tell this story.”