A trailblazing filmmaker wants to make sure Native stories have their place in the American narrative

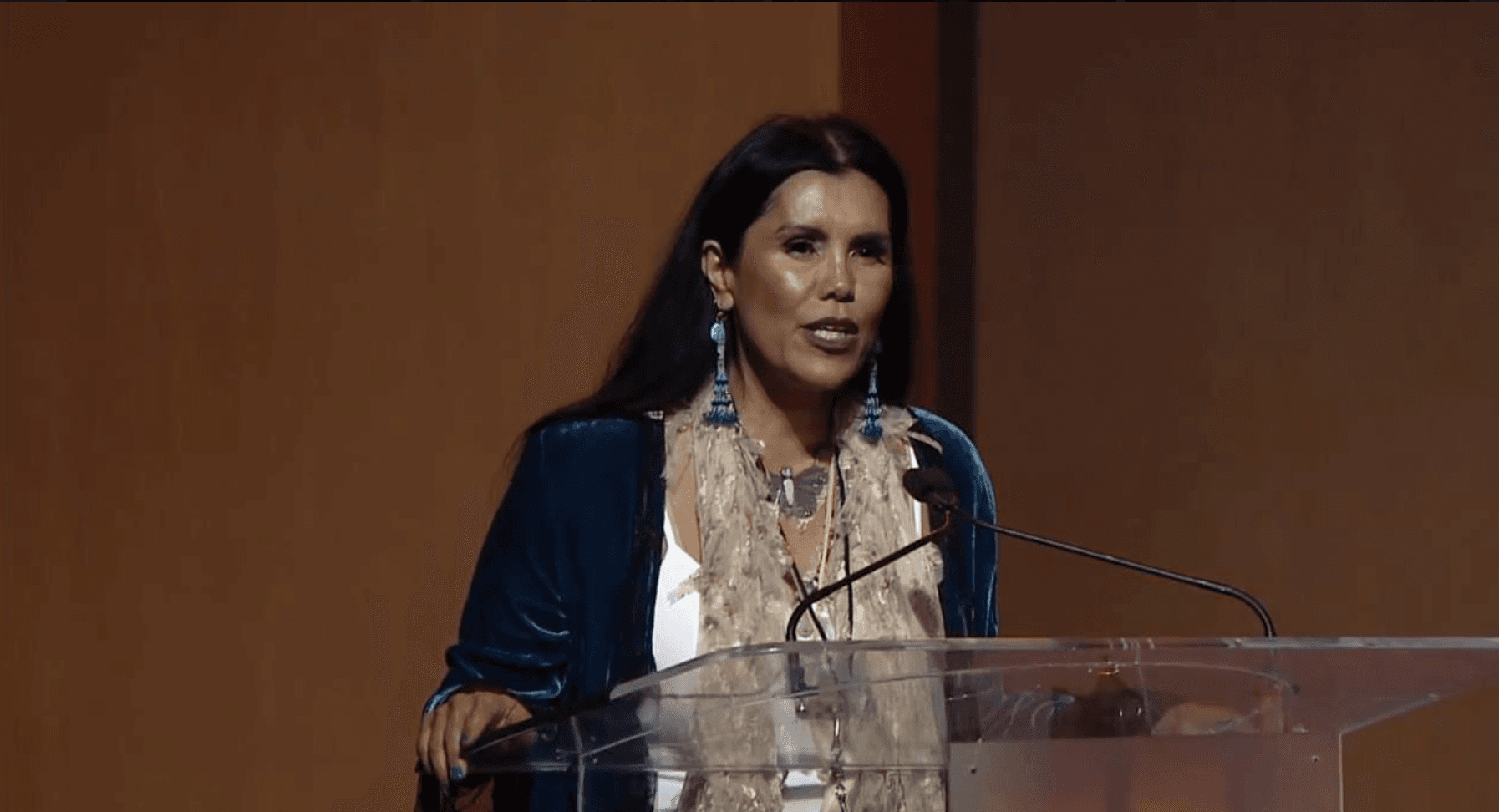

Joanelle Romero

When Joanelle Romero stepped onto the set of “The Girl Called Hatter Fox,” she made history.

She was the first Native American to carry a lead role in a contemporary film, which aired on TV in 1977. It was also the first modern, Native woman story produced in the United States.

Romero was born into Hollywood, the daughter of an actress, Rita Rogers, who starred in Elvis Presley movies. At the age of 12, Dennis Hopper became Romero's legal guardian. Yet her story is more than a laundry list of movie industry name drops.

As the founder of the Red Nation Celebration Institute, Romero is steering the narrative around First Nation people, in TV, film and music.

Christabel Nsiah-Buadi: Let’s start with your role in “The Girl Called Hatter Fox.” It was the 1970s. Given the time, what was the experience like in terms of its production and story?

Joanelle Romero: I wasn't raised on the reservation. I was raised in Hollywood and so I didn't experience a lot of direct racism. When I did this film, it was very challenging because I directly experienced racism. I remember in my hotel room, I called my mom, and I said, "They don't like me because I'm Indian."

I was 17, 18 years old, and it was really an intense moment for me, because in my immediate home there was no racism.

How did you process that?

It's been a lifelong journey to process it, and come to terms with it, especially within the film industry. I was the highest-paid Native actress on episodic television for years. Fourteen years ago, NBC, CBS, ABC and Fox have completely written us out of the narrative for Native women. Every once in a while, there'll be a Native actor, man on episodic shows, but yeah, they've completely written our Native women out of the narrative, and it's been 14 years. I spoke with a network a while ago and they said, "Well, we had one actress." I was embarrassed for them. It was like, how can you even say that?

We have a long way to go with this narrative. There was a film, that just won all the awards at our [recent Red Nation Film Festival], called "Wind River." That film had Oscar buzz on it, and it's about our missing and murdered women. That I think has opened up this whole conversation to lend itself to Native women in film. Where are we?

Why do you think Native women have been written out of the narrative?

It's the doctrine of domination and dehumanization. It's generational, passed down from when our lands were taken from us. The whole mission at that time was, if you wipe out the women and children, they don't have a nation. When you hear that over and over again, and it's proven over and over and over again, it just becomes a norm. Then we get written out of the narrative.

I'm an Academy member. I'm the only Native director, producer who made the preliminary documentary shortlist for Oscars (for the film “American Holocaust: When It’s All Over I'll Still be Indian"). Why am I not directing episodic television or anything? Why haven't I even been offered to shadow someone on episodic television if they're so concerned about anyone's ability to direct? There are really no nurturing programs.

When did you become an active advocate for the representation of First Nation people in the media?

I don't call myself an activist, and we're not a cause, and we're not associated with any movement. We're professionals, directors, writers, actors, crew. We're professionals. With that said, I did this film for Ted Turner. It was called "The Miracle in the Wilderness." It was a Christmas movie about how they brought Jesus to Indians; it was a weird thing. I was so tired of being in a buckskin and saying, "Me want more stew meat."

I was just praying on this one day and looked up at this tree and saw this beautiful hawk with her family. I said, "I'm just going to go into directing, and start doing my own thing, because I'm not going to wait, I'm tired of waiting." Twenty-three years ago, I started our non-profit organization, which is Red Nation Celebration Institute. We're the longest standing Native arts and cultural organization in Los Angeles.

Under that banner we have Red Nation Film Festival and in that body of Red Nation Film Festival we've always included Native women in film and television. Then we created Native Women In Film Festival. Then we have Red Nation Television Network which launched in 2006. We launched our online streaming network before Netflix, before Hulu. We were way ahead of our time. We have 10 million viewers in 37 countries. In 2018 we are launching a newsroom of all Native content. We're also uploading 300 new titles on our network.

Who is producing a lot of this content?

We have a staff of five people that help with everything from branding to graphics to uploading, editing, all of that stuff. As far as content, it's all of our filmmakers. We also have a board of directors. There's a lot of A-list celebrities on our board, as well as chiefs of different tribes across the country, as well as Native actors, and actresses. They really help us, guide us with our mission, and to stay on point with our mission and not get derailed.

Our thing is "Natives in charge of their narrative." That's going to be our narrative for quite some time, moving forward, until something changes in this industry.

When our kids, our youth don't see themselves in media, that's a big issue to me. We have the Native youth suicide issue in our communities that is very prevalent. I feel personally that is because they don't see themselves, there's nothing for them to relate to. It's like, what's the point?

It's also the murdered and missing women. I'm a survivor of sexual assault and molestation. It's really important that, as a Native woman, mother, grandma that I speak up.

What do you consider to be some of your biggest successes? Or achievements?

Well, first of all, the birth of my two children. And my grandbaby, now that I'm a grandma.

As an artist, it's being a member of The Academy. That has been my biggest dream since I was three years old, when I started doing plays with my mom and my grandpa. I used to hold the brush and recite my Oscar speech over and over all the time.

To be able, as an artist, to do a lot of "firsts," like with” The Girl Called Hatter Fox.” Because it was a Navajo girl who'd been abused and she was off the reservation, I went in [to the audition] with no makeup, my hair uncombed, barefooted, no jewelry, torn jeans. When I went in to the director and producers, they said, "Your name?" I said, "I'm Hatter Fox." Right then and there, they said, "You have the part."

In regards to our community, I'm very proud that we started our non-profit 23 years ago. We just keep growing and growing and moving forward with our narrative, and not taking no for an answer. That word does not exist in my vocabulary.

Check back here over the next few weeks to read other interviews in our series, "The Media Disruptors," with:

Bhakti Shringarpure (Feb. 23)

Nancy Wang Yuen (March 15)

Christabel Nsiah-Buadi is the creator and editor of “The Media Disruptors” and a public media producer. She also writes about the media, culture and politics. You can follow her on Twitter: @msama.