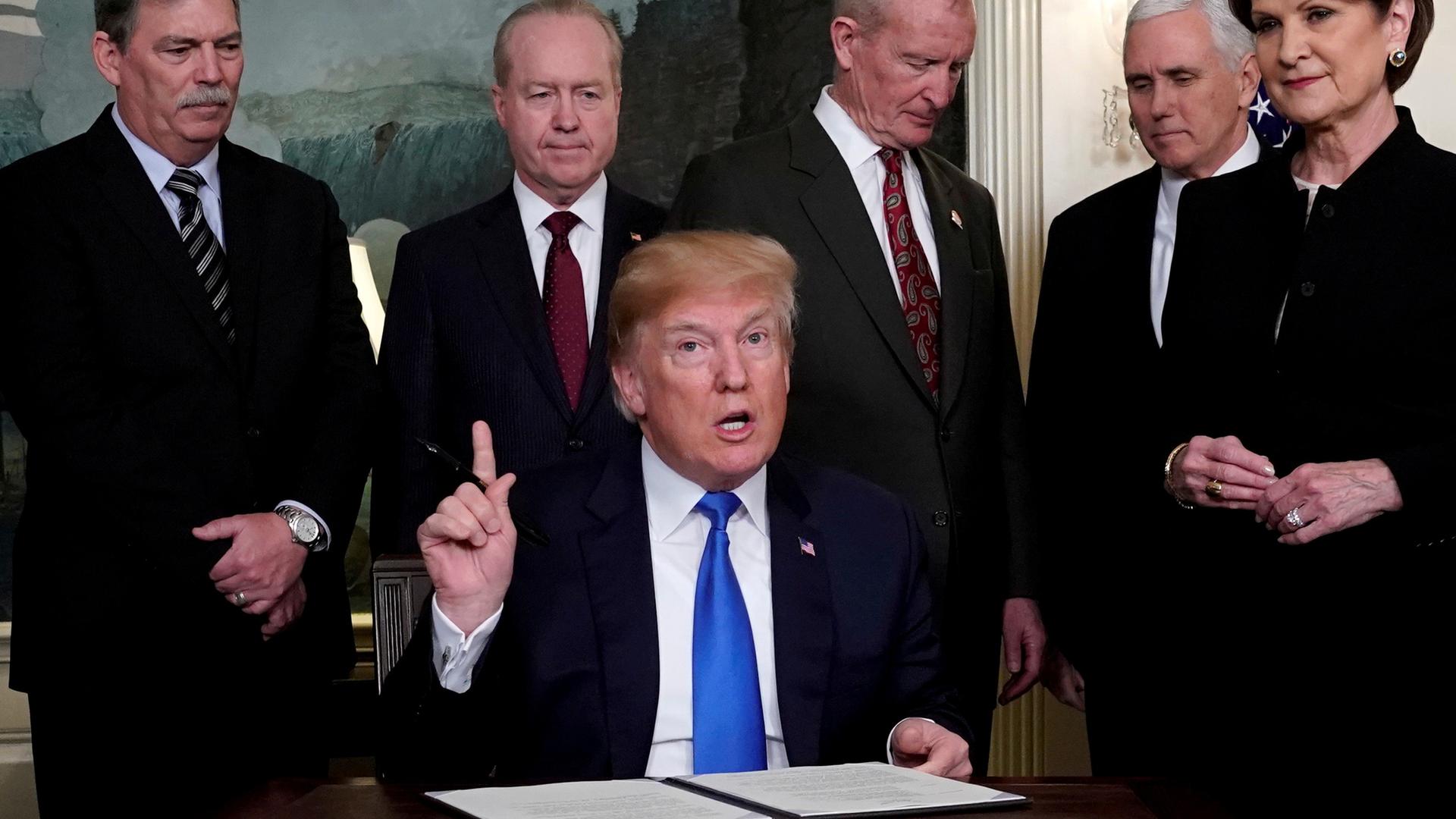

President Donald Trump, surrounded by business leaders and administration officials, prepares to sign a memorandum on intellectual property tariffs on high-tech goods from China, at the White House in Washington, March 22, 2018.

President Donald Trump sent off a barrage of tweets this weekend, questioning, among other things, the Russia collusion investigation and the intelligence of Lebron James. In other words, it was a typical weekend. But lost in the mix were two tweets about economics.

Trump said his tariffs will allow us to pay down “large amounts” of the $21 trillion debt. Is that possible? Could tariffs raise enough revenue to substantially reduce the debt?

“No, I don’t think so,” said economist Lee Branstetter at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Thea Lee, the president of the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, said, “Just on a number of fronts, this is a silly claim.”

And economist Michael Klein with the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University just outside of Boston simply laughed at the tweets.

Let’s start at the beginning. How do tariffs work?

Michael Klein said a tariff is like a national sales tax “except it’s special in that the sales tax is only on foreign goods.”

That tax is paid by an American importer (then passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices). Klein said to think of it like going shopping: “When you go to the store and you buy an article of clothing and you don’t pay what it says on the tag, you pay more because at the register they impose a tax,” he said. “The tax [tariff] is collected by the customs authorities.”

That’s how the US raised a significant amount of money during its early history “except historically in the period, the government was a much, much smaller part of the economy,” Klein said.

Related: The US tried extra-high tariffs before, in 1930. It was a disaster.

As the nation grew, the government needed more revenue. In 1913, 42 states ratified the 16th Amendment, granting Congress the power to impose a national income tax.

Late last year, income tax rates were slashed, and Trump’s tax cut is expected to add $1.5 trillion to the debt over the next decade. Could tariffs be a way to fill that hole?

Not even close.

“The magnitude of the tariff revenue is utterly inconsequential relative to our national debt,” Thea Lee said.

Trump’s current tariffs of $50 billion on Chinese imports, at 25 percent, would raise about $12.5 billion annually, assuming trade between the US and China continues at current levels and the tariffs have staying power.

“In an ideal world, if your tariffs are working they should be targeted and they should be short term, in which case they won’t raise very much revenue,” Lee said. “So, if they achieve their desired goal, which is to deter imports and to help American producers and manufacturers, then, in fact, there won’t be a whole lot of imports, and there won’t be a whole lot of tariff revenue.”

Related: Philadelphia ice cream is a luxury in China … with a scoop of import tax

The Trump administration is also considering slapping additional tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese imports at a 25 percent rate. That could raise $50 billion a year in import taxes, again assuming that trade between the US and China continues at current rates. But those additional tariff revenues would also come at a steep cost.

“If tariffs massively escalate, then we could be talking about a much more intense global trade war,” Lee Branstetter said. “And that could have a depressing effect on [gross domestic product], and that could lead to less federal government tax receipts from income and other taxes.”

So, while tariffs would give some revenue through an import tax, they would simultaneously take away by slowing growth and income tax receipts.

“And I think already, we’re starting to see evidence that trade-policy uncertainty is preventing US multinationals and other firms that are highly reliant on international trade from making the kinds of investments they would otherwise want to make,” Branstetter said.

And as China retaliates with tariffs on US goods, American exporters — like soybean farmers who currently sell to China — are losing out on a huge export market.

Also, if tariffs on Chinese imports worked spectacularly — stopping imports entirely — Michael Klein did the math on how much we’d raise from import taxes: “Tariff revenue would be zero.”

But if the US stops importing things like, say, toys from China because they’ve become too expensive due to tariffs, parents will still want to buy their kids toys. So, Americans would have to start making them again at home, thus creating more jobs, right? Well, it sounds nice, but economists say those toy-making jobs probably won’t come to Ohio or Indiana — they’d go to lower-wage nations like Vietnam or Indonesia.

Related: What turns some law-abiding Canadians into smugglers? The high price of imported cheese.

For trade economists, all of this is pretty much as basic as it gets. In addition to teaching students at Tufts, Klein launched a nonpartisan website called EconoFact. It began during the 2016 presidential campaign and now has a network of about 80 economists.

“The reason I started EconoFact was [because] during the campaign, a lot of claims were made that economists knew were just wrong,” Klein said. “So, many economists, myself included, felt that there should be a higher level and a better-informed discussion of economic policy.”

And if Klein were evaluating the president’s Sunday morning tweets for how much economic sense they make, what grade would he give that student?

“I would probably want to talk to the student and ask why that student had not attended class throughout the semester.”