Trapped by border closings, these young migrants are hiding out in an abandoned warehouse

Two migrants play checkers with bottle caps in an abandoned warehouse where they live on the Greek island of Lesbos.

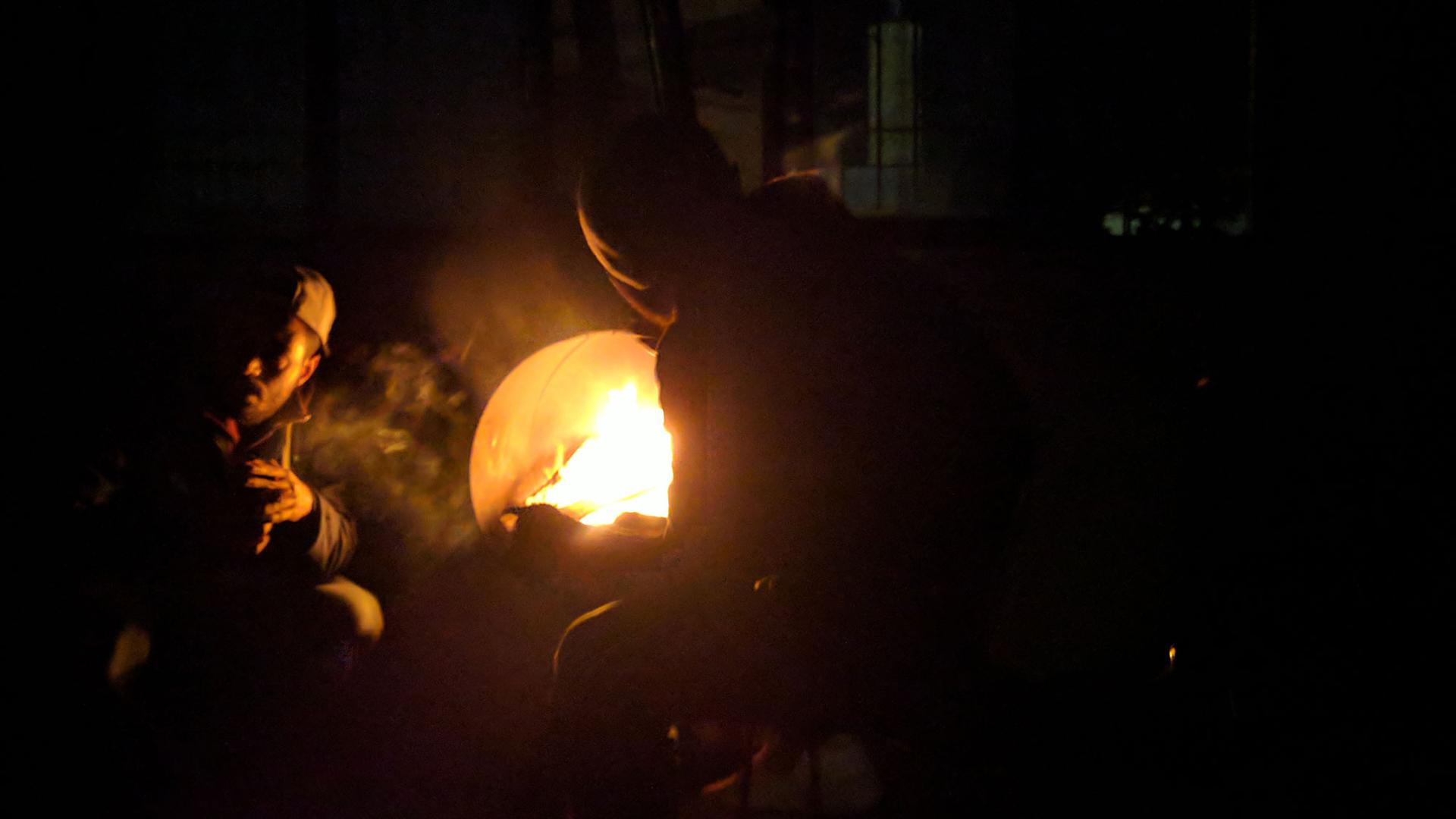

In a dark, abandoned warehouse on the edge of Europe, a group of young men are gathered around a fire with a nervous eye on the exit.

They came here to the Greek island of Lesbos from Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco in the hopes of pressing on to mainland Europe and to a better life, but they are stuck.

Their claims for asylum have either been rejected or placed at the bottom of the pile. Some have been waiting for more than a year.

If they are found by the police, they will likely be sent home. They are doing all they can to avoid that fate.

“They say we’re not refugees, we are immigrants, so we don't have strong reasons. But there is no one here who left his country without a reason,” says Yassin, a 24-year-old Tunisian, who gave only his first name for fear of arrest.

Yassin is one of about 20 young men from the Maghreb living in this decrepit squat, eking out an existence on their own, set apart from the overcrowded refugee camps on the island.

And there are many others hiding elsewhere in similar conditions.

Yassin spends his days volunteering at refugee centers. At night he and the others gather in the sparse concrete room of this old factory and try to keep warm. Some sleep in tents within its walls, others cram into side rooms with thin mattresses covering the floor.

Tonight they have two bags of flour, which cost less than a dollar each, to make bread for two dozen people.

“We are living under the mercy of God. Some days we eat, some days we don’t,” says another resident, 23-year-old Muhammad, from Algeria, who also gave only his first name for similar reasons.

They rarely let their guard down. Many of his friends have been caught by the police and deported.

“If the police come here, we run,” says Muhammad. “We run out of the closest door.”

Muhammad says he fled Algeria because of political repression, but his claim for asylum was rejected. He has been on Lesbos for 18 months now. Like most others living here, he went on the run rather than be sent back.

“I don’t want to go back to Algeria and I don’t want to stay here,” he says. “The island is a jail, and we are living in a jail within a jail.”

Another resident from Afghanistan who did not wish to give his name said he has been waiting to hear about his asylum claim for a year.

Their predicament owes much to the chaos that has taken over on Lesbos over the past few months. That chaos, and a hardening of Europe’s immigration policies, has meant that only the most severe of asylum claims are being processed properly.

The bottleneck on Lesbos came about due to a perfect storm of circumstances.

Under a deal between the European Union and Turkey from 2016, any migrants arriving on the Greek islands were supposed to be sent back to Turkey. Asylum claims would be processed on the islands, and migrants would not step foot on the mainland.

The deal marked a major turning point in EU policy. It slammed the doors shut in an attempt to stem the flow of migrants that had been causing panic across the continent.

But only 4 percent of arrivals have been sent back, according to the EU — fewer than 2,000 people.

People have kept coming. The island has seen an influx over the past couple of months of refugees from Raqqa in Syria and Mosul in Iraq — mostly women and children — stretching resources to the limit.

The mayor of Lesbos, Spyros Galinos, says Athens has turned the island into a “concentration camp” by keeping people there.

Today, around 60,000 asylum-seekers are stranded on the Greek islands. At Moria camp, a former barracks turned refugee site on Lesbos, more than 6,000 people are crammed into a space meant for 2,000.

The overcrowding means that asylum claims from people who aren’t from refugee producing countries like Iraq and Syria are being pushed aside or rushed and rejected. Many legitimate claims are falling through the cracks.

“People’s right to a fair asylum process can be at risk if European authorities take fast-track decisions just because migrants of certain nationalities are not usually granted asylum,” Oxfam’s Florian Oel told PRI.

“In some cases, it will be even more important to examine their cases in detail to establish if they are in need of international protection, or not.”

But it’s not just the waiting. Yassin says anyone not from Iraq and Syria is treated like a criminal the moment they step off the boat.

“We come like 50 people in one boat. We are like 20 Algerian and 20 Tunisia and 20 Moroccan. And the first day when they registered they put us all in the jail without reason. Without no reason,” he says.

Eventually they were released. But they have little hope at a fair shot of applying for asylum.

“My plan now, I really hope to sneak inside the ferry or the big cars, the containers. I will go to Athens, then I will complete my journey,” he says.

That is harder than it sounds. He’s been here more than a year, and has been trying since the summer to sneak onto a ferry to the mainland.

Yassin hopes to go to France, where his father lives. To do so, he will have to cross a continent that has changed dramatically in the last two years, when the migrant crisis was at its peak and more than a million people crossed borders at will.

In the meantime, he’d like to see a solution that takes care of everyone on the island.

“It's really terrible to see a woman sleeping in the tent in the rain always, and soon it will be snow, and they didn't get anything,” he says.

“People just come here because they want to find a peace. But then what do they find? They find a tent. It’s terrible.”

Richard Hall reported from Lesbos, Greece.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?