Mosquitoes and a dragonfly fly around a lit bulb on a hot summer in southern Spain.

Mosquitoes are, by far, the deadliest animals on Earth. More than 725,000 people die from mosquito-borne illnesses like malaria each year, and millions are affected by mosquito-borne illnesses, according to the World Health Organization.

Now new technology is being used to try to reduce mosquito-borne illnesses. In particular, introducing sterile male mosquitoes to a population can increase competition for female mosquitoes, eventually reducing the population by as much as 90 percent, according to researchers.

But introducing the mosquitoes to areas affected by mosquito-borne diseases can be a challenge.

“Not everybody lives next to a road. Even if roads do exist in some of these areas, they look very different when the rainy seasons hit. … And of course when it rains … you have pools of standing water and even more mosquitoes,” says Patrick Meier, executive director and co-founder of WeRobotics, a nonprofit with offices in the US and Switzerland.

So Meier and his team are testing a unique delivery method, too: drones.

In partnership with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Insect Pest Control Lab in Vienna, Austria, WeRobotics is testing out the technology and hopes to put it to use in Zika hotspots in Latin America.

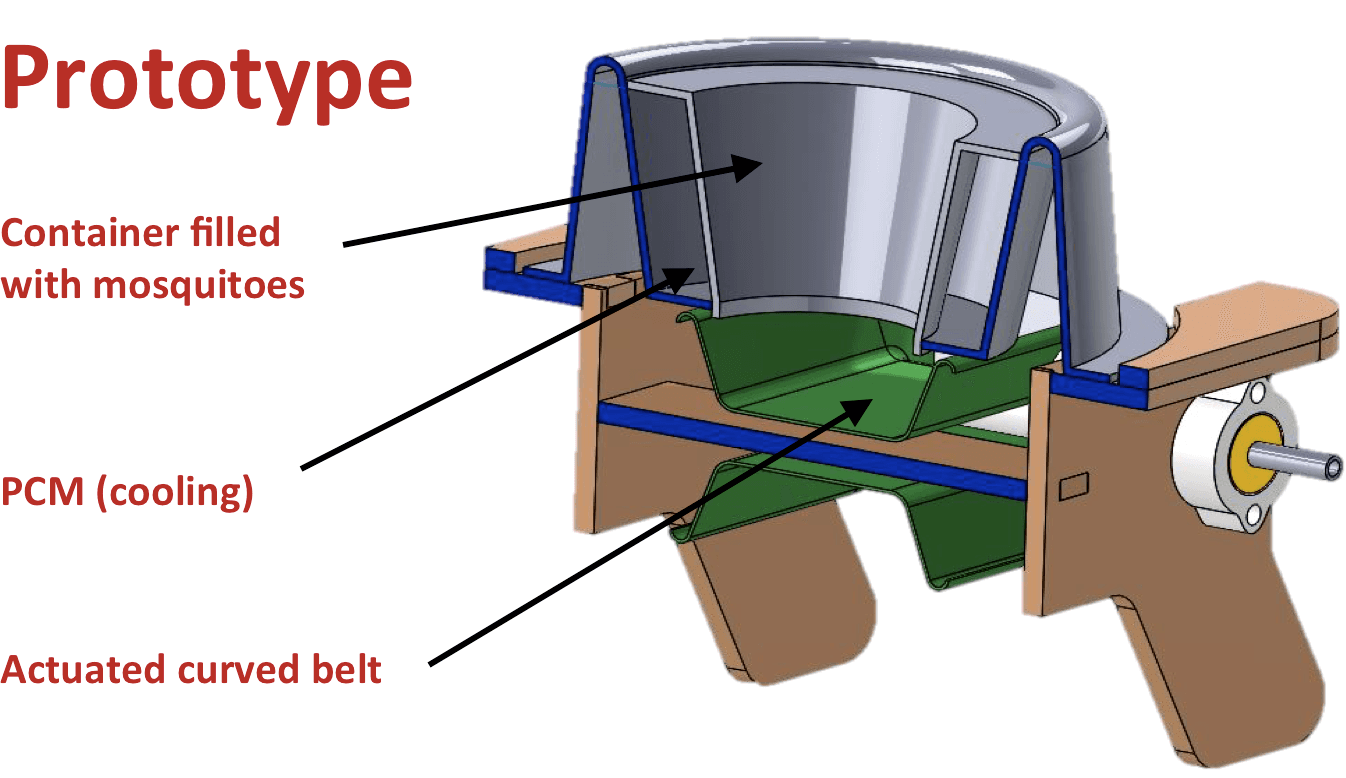

But releasing hundreds of thousands — if not millions — of mosquitoes comes with engineering challenges, Meier says.

“How do you take 100,00 mosquitoes, put [them] in a relatively small box and have them not kill each other?” Meier says. “You have to keep the mosquitoes in a kind of sleep state, which means you reduce the temperature within this ‘box’ between 4 and 10 degrees celsius.”

Other challenges include releasing mosquitoes in a uniform manner, Meir says. “You’re not releasing 100,000 as soon as you get to 400 feet. You’re trying to do a homogenous release over a gridded area. Remember, these mosquitoes are basically knocked out, if you’d like, or tranquilized. How do you ensure that as they’re falling from the release mechanism, they actually wake up in time before they go splat on the ground?”

WeRobotics will begin deploying these drones in the coming months, focusing on communities that are already deploying sterile mosquitoes on the ground, and providing education to locals about the project.

“This is frankly our bread and butter — training, awareness-raising, capacity-building and informing local communities can be used, and are being used, to improve their health,” Meier says.

Other methods to reduce mosquito-borne illnesses range from simple nets and vaccines to mass spraying of insecticides, but many have proved ineffective, costly, and damaging to the environment.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?