These Mongolian miners are making gold greener. Now they want their government to help.

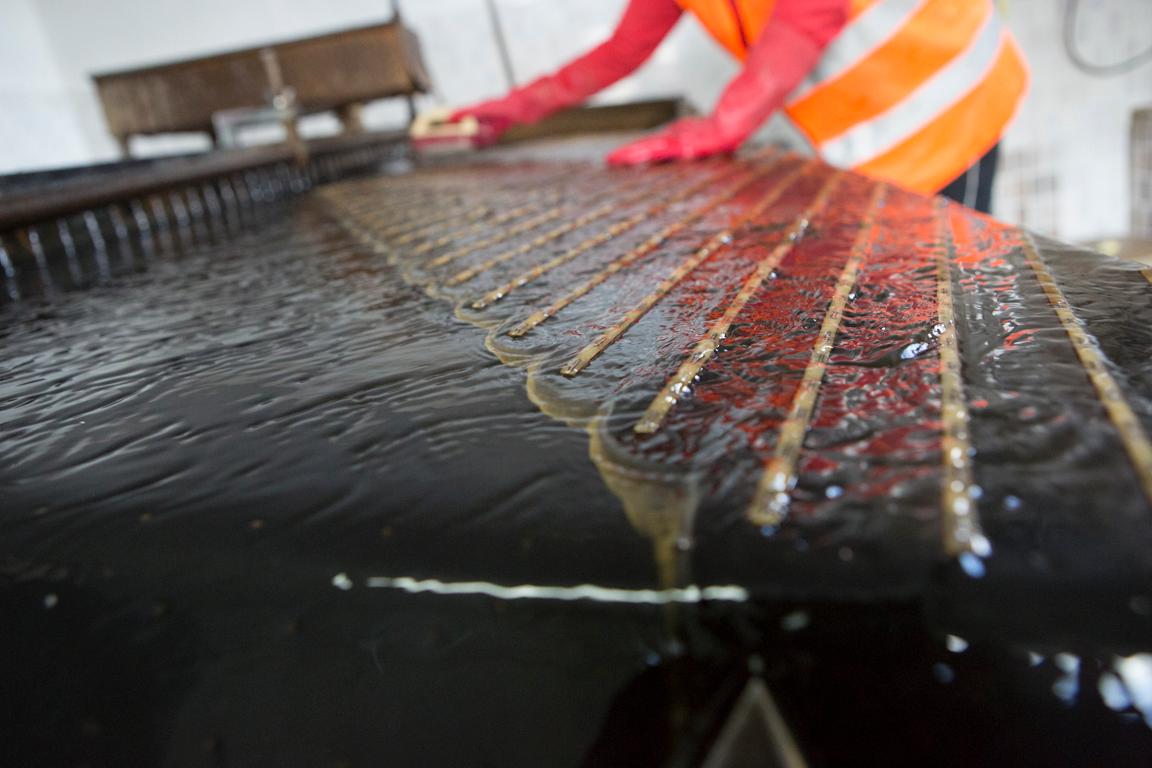

The new water-based process being used by some independent Mongolian miners can extract up to 80% of the gold from the ore and is much cleaner than processes using mercury or cyanide.

The narrow, black tunnel at the bottom of a 70-foot dirt shaft about two hours north of Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, is so small that you can’t stand up. But there are three men down here using headlamps to illuminate a section of rock where they’ve been digging for gold.

It’s grueling work, but it provides some of the few jobs available around here, and it’s important for the whole country. Together, Mongolia’s small and large gold mines produce about 10 tons of the precious metal annually, helping propel a mining industry that’s one of the largest drivers of its emerging economy.

But much of that gold has come at a cost far beyond the taxing physical labor. Until about a decade ago, many of Mongolia’s gold operations used mercury to extract the gold from the ore. And that was a big problem.

“Mercury can accumulate in the food chain and convert to methylmercury, which is toxic to humans,” says Saleem Ali, a professor of energy and environmental policy at the University of Queensland in Australia who’s studied mining in Mongolia.

Recognizing these health and environmental concerns, a decade ago the country’s government shut down all centralized gold processing plants that used mercury, forcing them to switch to less toxic methods. Small producers were left on their own, though, without the resources or know-how to make the change.

“We didn't really know what we were going to do at first,” says independent miner Narantsogt Belkhuu. Without good alternatives, many small operations kept using mercury.

But eventually Belkhuu and more than two dozen colleagues formed a processing cooperative, and, with the help of a government agency from Switzerland, they opened Mongolia’s first non-mercury processing facility for small-scale gold miners.

The facility in the town of Bornuur uses water and gravity — instead of water and mercury — to process gold ore. The ore passes through a crusher and roller mill until it’s pulverized into dirt, then heads to a “shaking table” where the tiny flecks of gold separate out.

It's cleaner than using mercury, but it’s a long process. And Ali says it’s not terribly efficient.

“Using just water, you might be successful with very high-grade deposits,” he says, “but you are not likely to be successful once you start to get to low-grade deposits.”

Ali says most big gold mines in Mongolia now use cyanide to extract gold, as do some artisanal miners. It’s less toxic than mercury, and it works better with those lower-grade deposits. But cyanide processing can still be harmful. So Belkhuu says he’s happy with the water process, which is safer and can still recover more than 80 percent of the gold from the ore.

His colleague in the cooperative, Dambiisurenjav Tovchinnamjargal, agrees.

“Sometimes we don't get anything from here,” Tovchinnamjargal says as he chips away at the walls at the bottom of that mine. “But whenever we do get gold, we actually make decent money."

And Ali says it’s vital income in a country without a lot of ways to make a living.

“This country has enormous mineral reserves, and they don't have much else, you know?” Ali says. “So the mineral resources could be a transformative contribution. But they need to be managed very carefully.”

And yet advocates for independent miners say the government has been slow to help them out by investing in more water-processing plants like this one. To date, only three have been built.

Ali says the Mongolian government is reluctant to encourage what it sees as a largely unregulated industry. But Belkhuu says people will keep digging up gold here with or without government help, and processing it with or without mercury.

“They still don't understand what we are trying to do,” says Belkhuu of the government’s reluctance. He says the government should invest in plants that help small-scale gold miners do their work without poisoning themselves and the environment.

And he wants his plant to be an example.

“My hope is to help the small miners operate well so that the government will support us,” Belkhuu says. “That's my hope.”

Related: Mongolian nomads say goodbye to herding, hello to smog