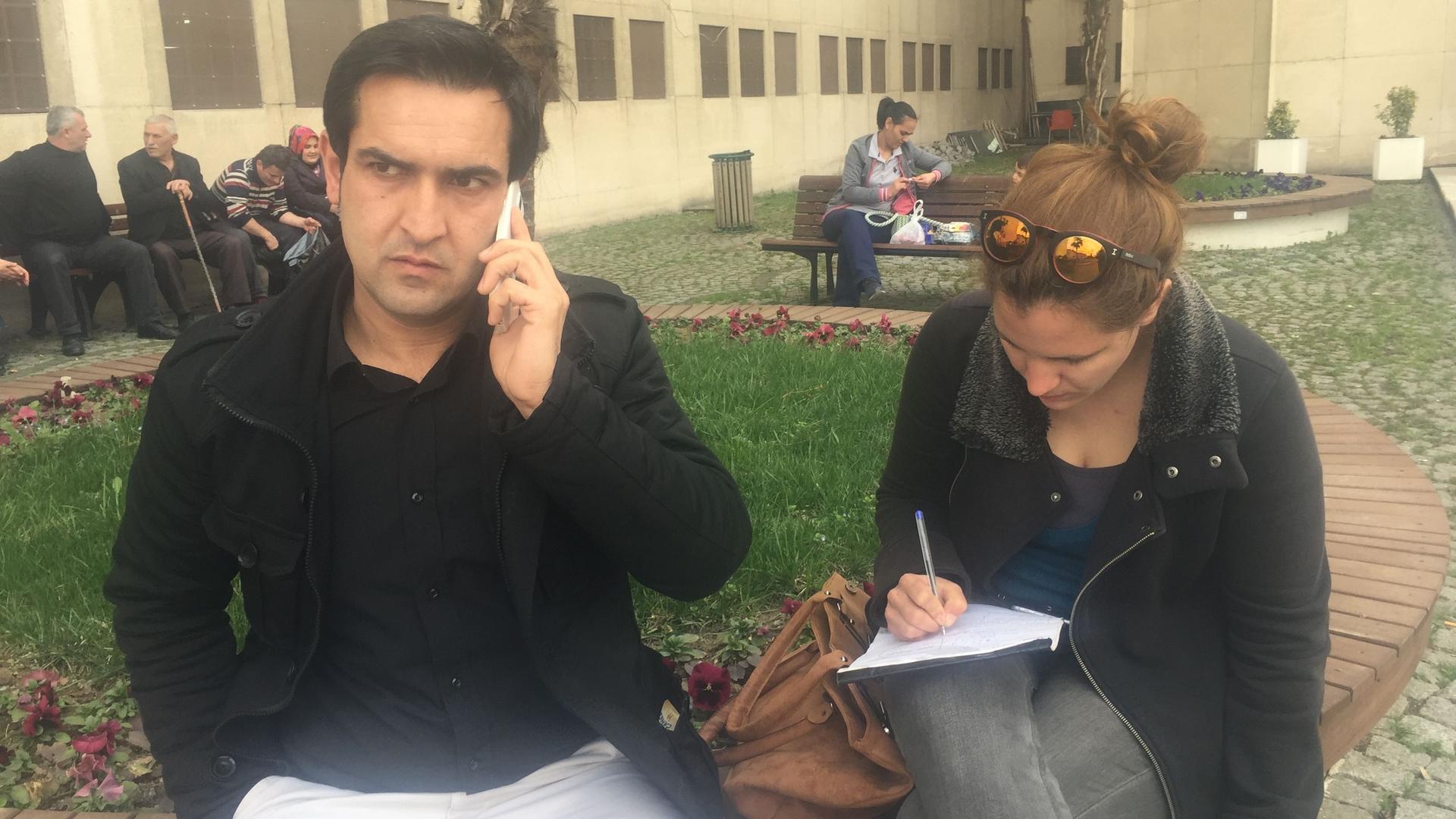

Mujtaba Haidar, left, with help from Stella Chiarelli, right, has visited detention centers, morgues, hospitals and cemeteries throughout Turkey, looking for his missing family. It's been a frustrating search.

As waves crash against a commuter ferry on the Marmara Sea, Mujtaba Haidar lurches forward in his seat. He’s afraid of the water now.

Haidar, 32, and his son Bahram, 8, are the only survivors in their family after a painful journey that began in Kabul almost two years ago and has yet to end.

On the night of Oct. 16, 2015, the family boarded a smuggler’s wooden boat headed from Çanakkale in Turkey to Greece. Haidar paid extra for a sturdier vessel — about $3,000 per person — hoping it would be safer than the rubber dinghies that many migrants were traveling in to make the crossing to Europe.

It was supposed to be a 20-minute ride to the Greek island of Lesbos. But Haidar says the boat lost its way.

“Everybody was checking through GPS,” Haidar says, replaying the scene in his mind. “The wind and waves [were] getting high. Suddenly a big wave crashed the boat. The boat split in half and [in] that second, the boat [went] under the water.”

Since the beginning of 2017, more than 2,400 refugees have died in the Mediterranean trying to cross to safer lands. Some of their remains have been identified, but many are buried without a name, marked only by a number. And many bodies may never be recovered.

Haidar, a businessman who worked with the US military back in Afghanistan, has been searching for his family with the help of Stella Chiarelli, a volunteer with United Rescues, an organization that tries to find missing refugees.

It’s been a frustrating search.

On this morning, Haidar and Chiarelli are taking the ferry from Istanbul to the city of Bursa, Turkey, close to where Haidar’s boat went under. They’re going back to a morgue they visited the year before. Before, they were looking for any trace of Haidar’s missing family. Today, they’re searching for information on how Haidar can give a DNA sample.

When bodies are pulled from the sea and taken to Turkish morgues, coroners collect DNA and keep the samples for five years. If a relative identifies a body (either in person or from a photo), the relative can then give DNA to see if there’s a match. Some refugees in Turkey and Greece have been able to identify their missing loved ones and have held funerals for them.

But after two weeks, unclaimed remains are buried in Turkish cemeteries with a number on the gravestone.

Haidar and Chiarelli have visited detention centers, morgues, hospitals and cemeteries throughout Turkey. Chiarelli has even searched in Greece without any solid leads.

One problem Haidar keeps running into is that the Turkish government won’t accept a DNA sample collected at a private hospital, but government hospitals won’t allow Haidar to give DNA.

“I’ve called the Red Cross in Turkey,” Chiarelli says. “I’ve talked to some lawyers in Turkey and some organizations, and no one seems to know how to get … samples to the morgue in Turkey to try to find a match.”

Three hours later, Haidar and Chiarelli arrive in Bursa. I’m traveling with them on this trip, but when we get inside the morgue office, two Turkish attendants tell me to leave.

“They are having some problems with the fact there is a journalist here,” Chiarelli whispers to me, embarrassed. “They say if you can leave the room, they can give me more information.”

Ten minutes later, Haidar and Chiarelli emerge, looking frustrated. Both light up a cigarette. Haidar says they showed him a website with images of unidentified corpses. Photos were supposed to be taken of all the bodies found across Turkey from at least two years ago, and they are slowly being uploaded on the site.

None of the photos appeared to be of Haidar’s family, though some of the bodies pictured were unrecognizable.

But what about giving a DNA sample?

“It’s really, really confusing,” Chiarelli says. The district attorney’s office in Istanbul told them to go to the office where the autopsies were done but then they got sent somewhere else. “So this is always what happens. Every person always sends us to a different place,” she says.

Chiarelli calls the Bursa district attorney’s office in a café near the morgue. They tell her to come into the courthouse. Once we get there, though, an aide tells Chiarelli he can’t help her. No one seems to know where Haidar or his son can give a DNA sample.

We board the ferry back to Istanbul, empty-handed. Haidar and Chiarelli are exhausted. Chiarelli says at least the morgue attendants saw that she’s still following up with the case. Maybe they’ll contact her if there’s any new information.

But Haidar is skeptical he will find any answers in the search for remains. It’s not just the runaround he’s been getting. Haidar believes his wife and kids may still be alive somewhere, perhaps in a refugee detention camp, where they can’t contact him. He has asked authorities and other refugees who have been detained about such camps. But no one has answers for him. Still, that theory gives him hope.

“The first thing I can cope with the situation, to pass my day and night, is the hope I have in my heart that I can find them,” Haidar says.

“The first thing I can cope with the situation, to pass my day and night, is the hope I have in my heart that I can find them.”

Back in Istanbul, it’s Bahram, his smiling, chubby-cheeked son, who helps Haidar wake up every morning. Bahram goes to a Turkish school and now speaks Turkish better than his native language, Farsi.

“We left Afghanistan because there was war and fighting,” Bahram says. “I’m happy here. I have so many friends, I can’t count them.”

Father and son have a quick breakfast together before Bahram heads to his Turkish school and Haidar goes to work in a hotel. But the memories flood back while Haidar sits at his receptionist desk: his wife Shila dolled up in an Afghan dress looking flirtatiously at him before attending a Kabul wedding, his daughter Zahra taking care of her brothers, his son Behzad learning to swim.

“I look alive but I’m dying inside every day,” Haidar says, pausing to catch his words.

Meanwhile, Chiarelli persists in her search even when Haidar isn’t there. She says if she doesn’t help Haidar, no one will. She’s an archaeologist turned refugee volunteer.

“These are people, these are not only numbers. They have names, they have families … I see the pain that these people go through and how lonely they feel,” she says.

Two months after the Bursa trip, Chiarelli and I meet Nadir Arican, a forensics specialist at the Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine. And he finally provides an answer of sorts that Haidar couldn’t get from government agencies.

“There is no central DNA bank. We have thousands of DNA samples, and it’s kind of impossible to match everything without a national bank,” Arican says. “Unless a person can point to a specific body and say, 'This is my relative,' there’s no process to do the test without a body.”

Haidar says he’s not surprised when Chiarelli tells him the DNA lead appears to be a dead end. He wants to continue his search, but he also knows he has to move on for Bahram’s sake. Haidar has applied for a Special Immigrant Visa to go the United States. It's for people who have worked with the US military, like he did in Afghanistan.

But Haidar is torn about what to do.

“I don’t have to make a decision until and if my American visa comes through,” Haidar says. “And I’m not sure I can leave until I find my family.”

If you have information that could help Mujtaba Haidar find his missing family, contact United Rescues at contact@ur-missingpersons.org or 90 507 851 33 10.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?