The Sierra Club is organizing grassroots activists to push Cleveland’s city leaders to commit to 100 percent renewable energy by the year 2050.

More than 250 mayors from around the country convened in Miami Beach this week at the annual United States Conference of Mayors and vowed to buck President Donald Trump's inaction on climate change. The mayors, a mix of Democrats and Republicans, signed a resolution to increase efforts to combat climate change and commit to transitioning to renewable energy.

Cities have been pushing for stronger action on climate change for years, but the efforts are taking on greater intensity since President Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the Paris climate accord in June. Environmentalists have been taking advantage of this supercharged moment, pushing mayors to move toward 100 percent renewable energy, making the case that it isn't just good for the environment — it's good for local economies and the health of a city.

Consider the case of Cleveland, a city divided by the Cuyahoga River between east and west. The East Side, where Jocelyn Travis is from, is largely African American.

“Let me show you where we grew up playing in this area,” says Travis, speaking near some ballfields. “All of my brothers grew up playing baseball. And so we had many family outings in this area and had no idea … ”

No idea about the pollutants belching from a nearby coal-fired power plant.

“This was the sixth-worst coal-burning power plant in the country,” says Travis, referring to a 2011 report from the NAACP that ranked power plants in terms of pollution affecting low-income people of color.

The Lake Shore Plant was shut down two years ago. But other sources of local pollution remain, such as cars, trucks and coal-burning power plants.

“Cleveland was in the top 10 cities that had the most preventable deaths related to air quality issues,” says Kristie Ross, a pediatric pulmonologist with Cleveland’s Case Western Reserve University’s School of Medicine.

Ross sees a lot of children from Cleveland’s East Side dealing with health issues related to air pollution: “Asthma, reductions in lung growth even in children who do not have asthma.”

And new epidemiologicalevidence suggests that poor air quality can also affect brain development.

But what do sick kids have to do with climate change? For one thing, the sources of local pollution — cars, trucks and coal-fired power plants — are also drivers of climate change. But the connection doesn’t stop there.

“The length and intensity of aeroallergen season is greater with climate change, both because of the longer warm season and higher carbon dioxide concentration,” says general pediatrician Aparna Bole, who is with Case Western Reserve and the American Academy of Pediatrics' Council on Environmental Health.

She says infectious diseases are also migrating northward: “We never saw so many tick-borne illnesses before this far north, now we do. That’s already happening.”

She calls climate change a “public health crisis,” but also an “opportunity.”

“All of the actions that would be required to transform into a clean energy economy, as well as a more sustainable transportation infrastructure — all of those interventions have immediate health benefits,” says Bole.

So back to Jocelyn Travis, who is now working with the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign.

“Ready for 100 is a campaign with the goal, nationally with a goal, of getting 100 cities to become 100 percent clean, renewable energy,” says Travis. (Target year: 2050.)

Nearly 125 mayors have already committed to reaching that goal, from Salt Lake City to San Diego to Abita Springs, Louisiana. Travis says they’re building a coalition of community activists to push Cleveland's mayor to join the list.

Mayor Frank Jackson has joined a group of 200 mayors dedicated to fighting climate change but has not committed to transitioning Cleveland to all renewables. (Jackson’s press office turned down interview requests to discuss this.) Travis admits, drumming up support to fight climate change in her neighborhood can be a tough sell.

“You’ve got a lot of unemployment, you’ve got a lot [of] health issues, there’s so many issues in the black community,” says Travis. “People are just trying to survive.”

So, when she’s out on the streets talking climate change, she’s not talking about rising sea levels or melting glaciers.

“Because we’ve got to make it relate to people,” says Travis. “Most of our households, our family or friends, we know somebody who has asthma, or we know somebody who needs a job.”

And jobs in renewable energy are coming to Cleveland soon.

“The first freshwater wind farm will be built about eight to 10 miles off the coast,” says Lorry Wagner, pointing toward the horizon of Lake Erie. Wagner is the president of LEEDCo, the Lake Erie Energy Development Corporation, a public-private partnership building a wind farm off the shores of Lake Erie.

“You get 3 to 5 times the energy from the wind [offshore] than you do on land because it is so much more sustained and higher speed,” says Wagner, who is spearheading the effort to erect six turbines, slated to be operational by 2019 and creating some 500 construction jobs. Eventually, he hopes to harness enough gusts from Lake Erie to power 10 percent of Ohio.

“When we start looking at our vision of where we could be by 2030, it’s more on the order of 8,000 jobs, building an industry, about $13 billion into the local economy,” says Wagner.

The wind farm is being privately financed. Still, Wagner says it’d be easier to move forward with more government support. The Trump administration wants to cut federal support for renewable energies in favor of more gas and oil exploration. It’s the same story coming from Ohio’s Republican-led state Legislature at the capital in Columbus.

Republican state Rep. Bill Seitz is leading the charge in Ohio to eliminate the state’s clean energy mandates and invest in natural gas.

“Ohio sits on an absolute fountain of natural gas,” says Seitz. “So, I say dance with who brung you to the dance, that is the resource we have, that is the resource that should be used for creating electricity in Ohio for at least the next 40 years.”

For many of Ohio’s conservatives, natural gas means jobs, and abundant, cheap energy. But while it burns cleaner than coal, natural gas still produces a lot of climate warming emissions.

Seitz says he isn’t concerned about climate change though, or the prospect of Cleveland committing to renewables.

“They’re free to do that right now, that’s perfectly fine with me,” says Seitz. “They can become as green as they want to be as long as they’re willing to pay the price.”

Seitz argues that turning away from natural gas will result in energy price spikes. He cites a testimony from Ohio’s Environmental Protection Agency that said that if former President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan were enacted, shifting away from coal-fired power plants, Ohio’s energy rates could’ve increased by close to 40 percent by the year 2025.

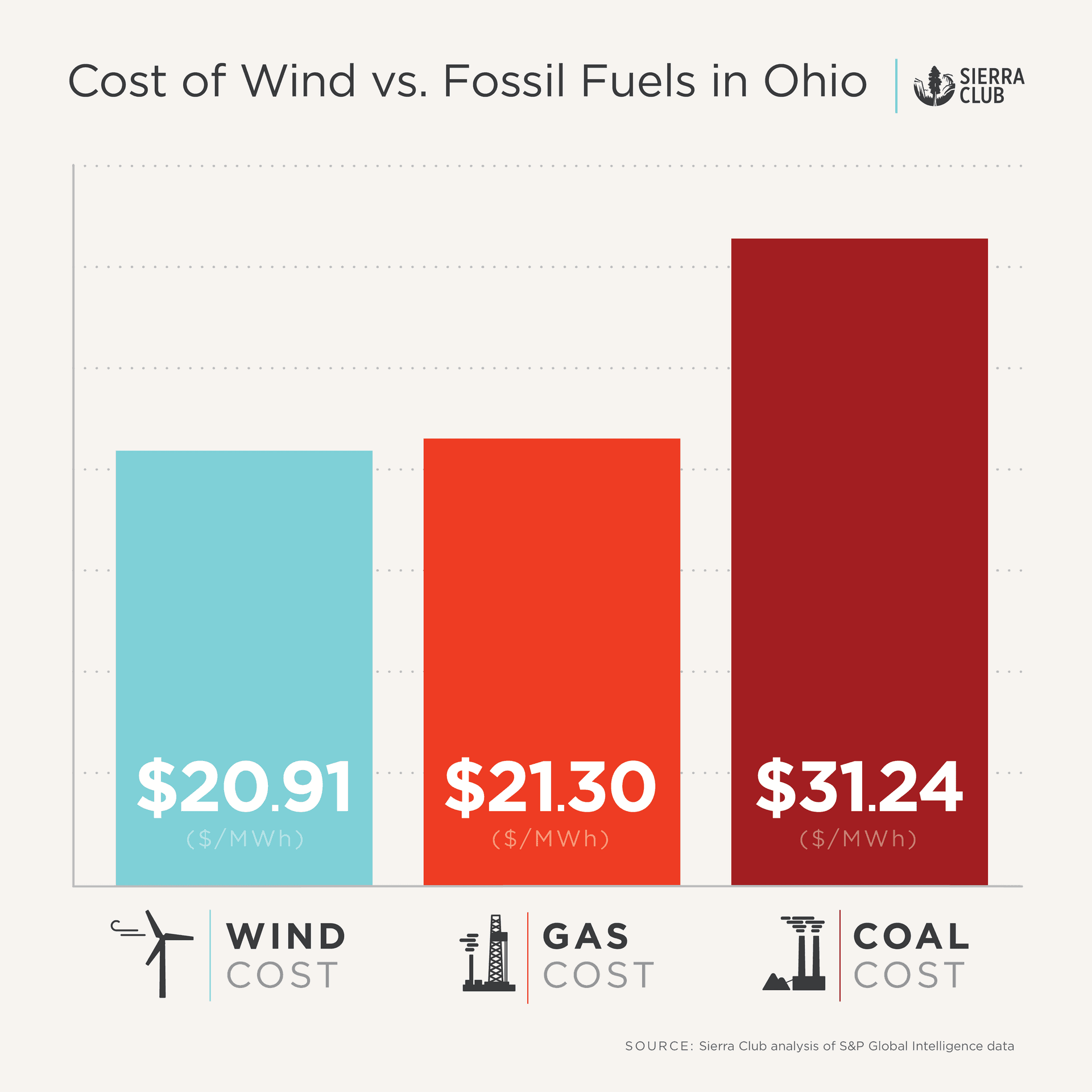

Environmentalists see things differently. The progressive organization, Public Citizen, says electricity bills in Ohio would've dropped nearly 7 percent by 2025. They point to statistics showing that the price of renewable energy has become increasingly cost competitive, and in fact, cheaper in parts of Ohio. More renewable energy in Ohio can also lower the overall wholesale cost of electricity.

As for jobs, it’s not a slam dunk for either side. Renewable energy generation — wind and solar — currently employ some 9,000 people in the state. Natural gas generation employs 2,500. Another 8,400 work in the natural gas fuel sector. (The jobs argument gets messy, and contentious quickly, with both sides claiming temporary construction jobs and tangentially related labor as evidence of support for their side.)

Jocelyn Travis says the lack of support from Columbus and Washington makes the push toward renewable energy in Cleveland more difficult, but it also deepens the resolve to go local.

“Cities have got to step up at this point,” says Travis. “A lot of cities throughout Ohio look to Cleveland to be the leader. I really believe that if Cleveland makes the commitment, other cities will come along.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?