I’m the great-great-great-great-grandchild of immigrants — but not everyone in my family wants to hear that history

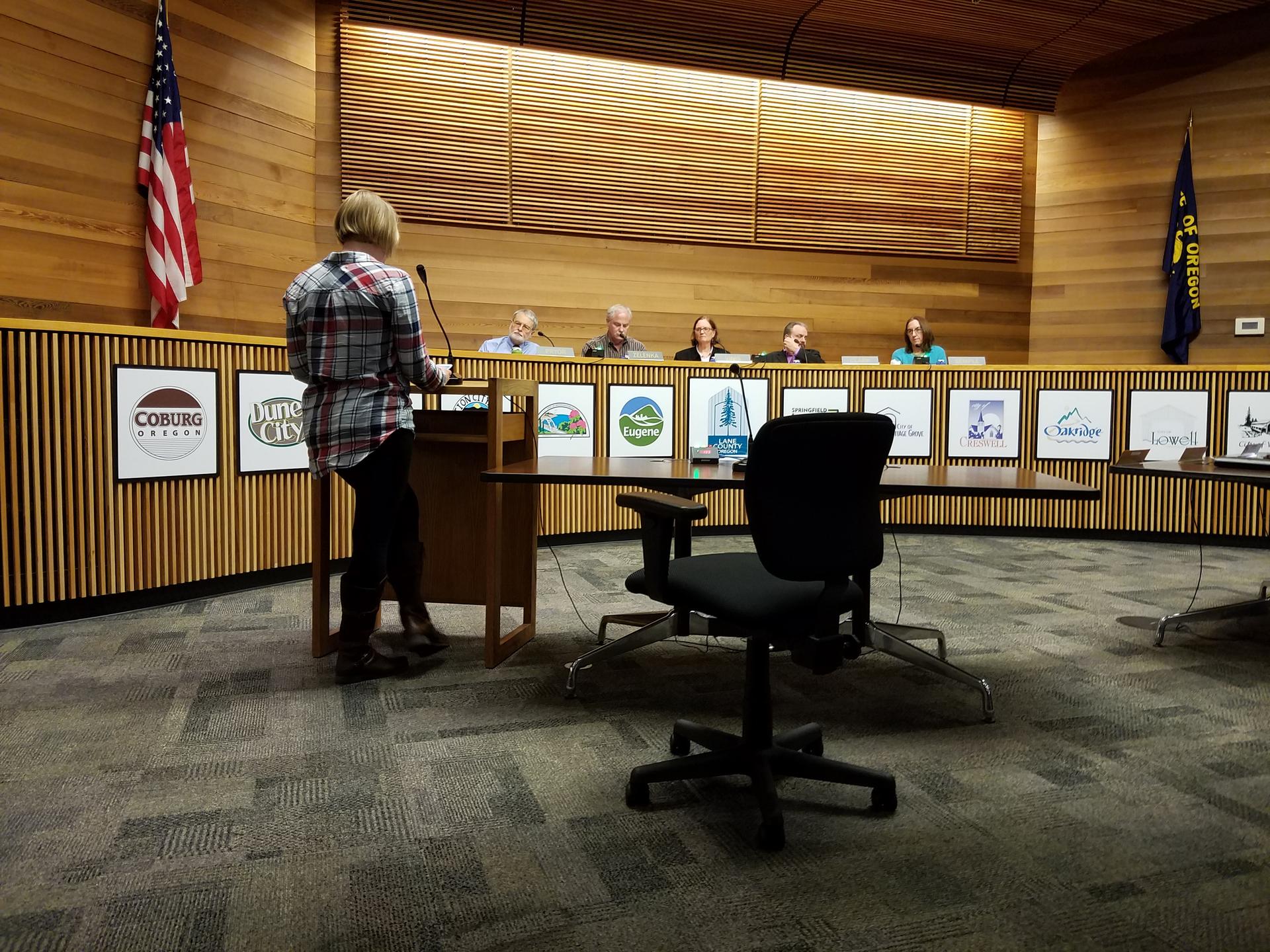

Sarah Stoeckl testifies before the Eugene City Council on March 13, 2017. The council heard comments on a proposal to prevent city resources from being used for federal immigration enforcement that isn’t related to criminal offense.

One evening in mid March, I was part of a full-house audience at the local city council meeting in Eugene, Oregon. On the agenda was an ordinance to prevent the city and police from using its resources to arrest and detain people whose only offense is violating federal immigration laws.

I can see how this kind of rule would make the job of law enforcement easier if entire sectors of the community were not afraid to speak to cops. Thirty-five people gave testimony, many of whom identified themselves as immigrants or the children or grandchildren of immigrants.

By the definitions in OMB Directive 15 — the federal standards for collecting data on race — I am white and non-Hispanic. You could call me an American citizen, a hillbilly, a redneck, an Appalachian American, a WASP. My relatives and classmates in the American South and Midwest get really hung up on the phrase “illegal immigrants,” and that leads them to some profoundly flawed logic. It goes like this: Illegal immigrants are criminals, by definition. Criminals are dangerous. Therefore, illegal immigrants are dangerous.

Personally, I would be much more comfortable in a room full of undocumented immigrants than I would be in a room full of my angry Texas relatives. I have tried to explain to them that the biggest difference between undocumented immigrants and the rest of the people in America is not some kind of moral inferiority, but a greater vulnerability to abuse and exploitation. I try to remember that opinions are generally based on experience, and my experience has been very different from most of the people who grew up in my culture.

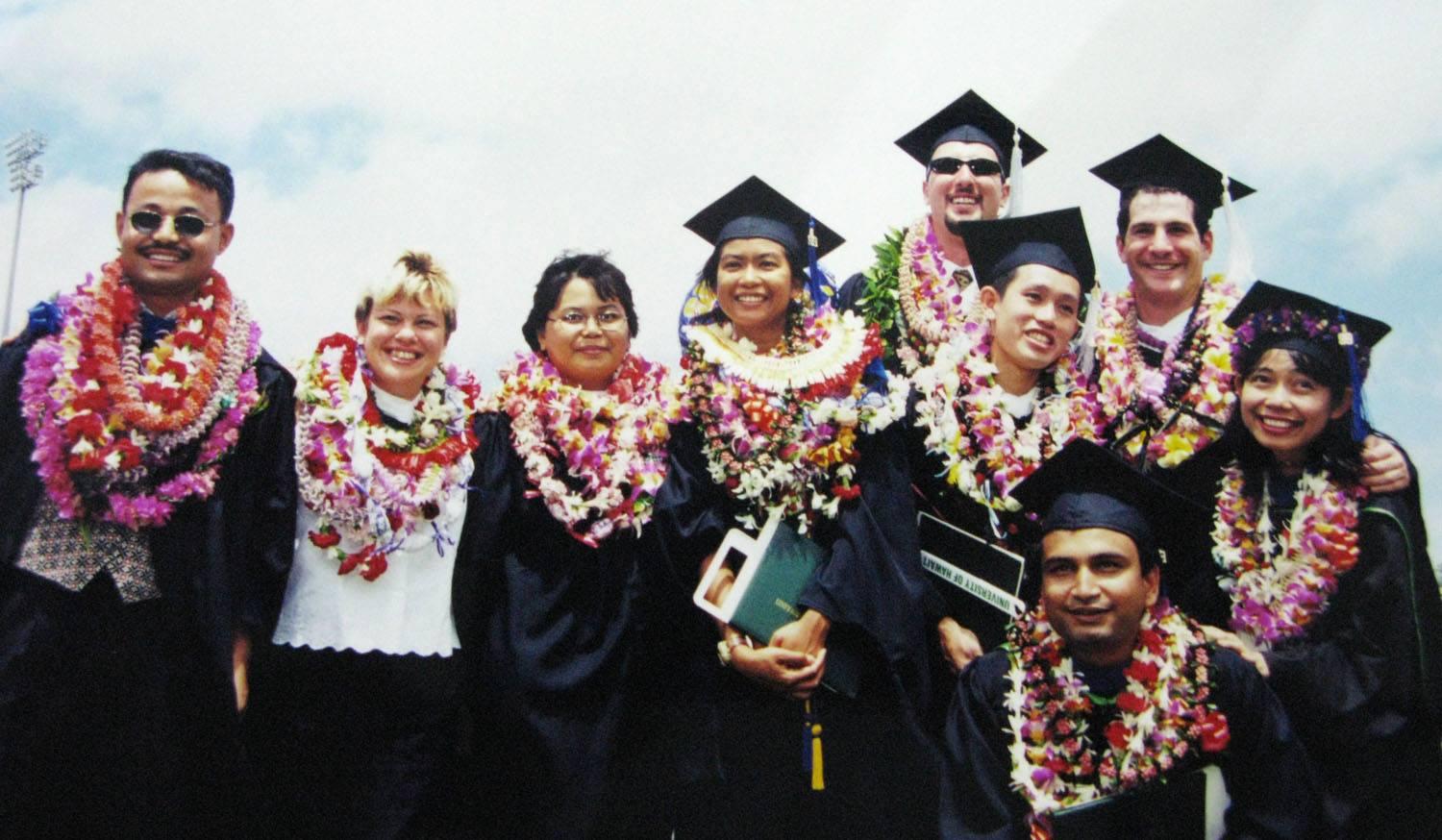

When I worked for a few weeks in another country without a work permit, waiting for the bureaucracy to process my application, the distinction between me and the undocumented residents in my own country vanished. When I lived at the East-West Center in Honolulu during graduate school, my Indonesian classmate, Nina, and I joked that we were twin sisters, separated at birth. When I ran out of money as a student, a woman who had come to this country as a refugee in a previous decade let me sleep on her floor for a few weeks. When I taught in a school where 70 percent of the families spoke another language at home, those students became my kids, whatever their status.

Part of the unique experience that gives me a sense of kinship with immigrants has been the journey of getting to know the immigrants in my own family history. A man named John Trudell inspired me to begin that journey. Trudell was an activist in the American Indian Movement. One night, around the turn of the millennium, I heard him say, “Find out what happened to your ancestors. Find out what happened to you.”

Less than a year later, my grandmother died, leaving behind a pile of family records. A few months later, I was living within walking distance of the Library of Congress and National Archives in Washington DC. Internet genealogy had just started to take off.

That my ancestors came to North America so long ago, and that I know so much about them, does make me a bit unusual in 21st century America. Which branch of my family tree was the first to emigrate to North America? DNA testing tells us that at least one branch of my family tree is Native American, so they got here long before Christopher Columbus or Leif Ericson. We don’t know for sure which branch it is, but our best suspect is Anne Basket, an ancestor of Johann’s wife. Anne, believed to be part of the Powhatan tribe, married an Englishman about 1685.

I discovered that I had several ancestors who came to the 13 British colonies because they had been kicked out of France for going to the wrong church — they were Huguenots. A pair of them arrived in Virginia in the middle of the winter with seven children and no way to provide for them. The community took up a collection of cornmeal and other items to help them survive the winter.

Another ancestor, a British sailor, escaped to Virginia from Bermuda, where there was no economic opportunity and a governor who would not allow the residents to leave. The sailor died soon after arriving in Norfolk, but his illegitimate son inherited his property. Illegitimate: a person unrecognized by law, but a person, just the same. The words illegitimate and illegal descend from the same parents.

My later ancestors fought in the American Revolution and the War of 1812, some under Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. Some of my relatives were named after him. For fighting against Indians, a few of my ancestors were granted land. Some of them owned slaves, and one of them, Mark, owned many slaves. Unusual provisions in his 1842 will lead me to think some of his slaves were also his children, so their descendants may well be my cousins.

I did not share that information with my angriest Texas relatives — they didn’t seem to be interested in the family history I had already shared — but he was their ancestor, too. A few of my southern ancestors fought on the Union side of the civil war, and my relatives, as a joke, pretend to be offended. My worry is that they might not actually be pretending.

As a child and teenager, I found history vaguely interesting, but the people in the textbooks were not particularly real to me. When the results of my DNA cheek swab came back, and I learned my maternal line had been in Mesopotamia around 10,000 years ago, my family tree got a lot bigger. The Kurds, Syrians, Israelis and Palestinians, were suddenly more cousins. The world news hurts a bit more when I think of them in those terms.

My grandmother did not show us the materials she had on our family history. My best guess has always been that she believed we would not be interested. Now, I am the one with the family trees, the stories, the photographs, and the history that makes sense of it all. My relatives and fellow citizens are often reluctant to let go of simple myths that divide Americans into sets that are worthy of having their rights protected, and those who are not. Their reluctance to embrace our complicated history leaves me feeling sad, frustrated and frightened about the direction this country is headed. So many people seem determined to repeat the mistakes of the past instead of learning and growing from them.

But the other night in Eugene, Oregon, the city council voted unanimously to approve “Protection for Individuals.” Then I cried tears of joy, love and relief for my human family.

Rebecca Morrison is a writer and education consultant in Oregon. She first began to tell us this story in our Facebook discussion group about immigration in the US, the Global Nation Exchange.