Black and Muslim, some African immigrants feel the brunt of Trump’s immigration plans

Akinde Kodjo-Sanogo, in New York, is a community organizer with African Communities Together. Since the election of Donald Trump, the group has been mobilizing to offer legal information and assistance to its members, who feel particularly vulnerable in Trump’s immigration agenda.

“My heart shivered,” says Martins Akinbode-Busayo, 35, a Nigerian health worker who fled his country in 2015. His government targeted him for helping gay people access HIV treatments.

In 2014, Nigeria passed a law that criminalized not just homosexuality, but also the organizations that support gay people. He applied for asylum in New York last year, and is awaiting the outcome of his application. But he felt despair after Donald Trump’s presidential victory.

“It’s sad news for me!” he remembers thinking. “I couldn’t sleep, I worried about what was going to happen.”

Amaha Kassa is an immigration lawyer and founder of African Communities Together, a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of African immigrants. He says he has been addressing anxieties like Akinbode-Busayo experienced many times since the election of Donald Trump.

“African [immigrants] around the country are confused and upset by the rhetoric and the threats,” says Kassa, 43, who leads the group of nearly 2,000 members between New York and Washington, DC. He estimates that several hundred of them are at risk of deportation under a new administration that promised a crackdown, but has said very little about comprehensive immigration reform.

They’re black, nearly half of them are also Muslim and they heard Trump’s campaign promises: He will not tolerate the undocumented and he wants to prevent people from Muslim-majority countries from entering the US.

“They want to know ‘what does it mean for me, for my family?’” says Kassa.

According to a 2016 study by the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, a national advocacy organization, and the Immigrant Rights Clinic at the New York University School of Law, black people in America have a higher chance of coming in contact with the criminal justice system, which makes them more susceptible to police violence.

Members of African Communities Together remember the death of Guinean immigrant Amadou Diallo in New York in 1999. He was mistaken for a serial rapist and shot 41 times by plainclothes officers. More recently, Alfred Olango, who came to the US as a refugee from Uganda, was shot to death near San Diego last year. The officers involved will not be charged with a crime, though his family says they will continue to pursue legal options.

But for African immigrants, these encounters with police also make them more deportable.

Trump has begun to sign executive orders — instructions for the Department of Homeland Security and Immigration and Customs Enforcement — that codify this risk. In one order, which he signed on Wednesday, he asked the agencies to focus on the deportation of undocumented immigrants convicted of crimes. But he also prioritized those who “have been charged with any criminal offense, where such charge has not been resolved” or “have committed acts that constitute a chargeable criminal offense.”

No conviction necessary.

For black African immigrants, any encounter with the police then becomes a chance for deportation. It’s an expansion of the kinds of deportations that took place under the Obama administration and earlier. From 2003 to 2015, while black immigrants represent only 5.4 percent of the undocumented population, they made up 10.6 percent of all newcomers in removal proceedings, according to the report by the Black Alliance for Just Immigration and the Immigrant Rights Clinic.

“The first folks to be targeted by some of [Trump’s] proposals are people who had contact with the criminal justice system,” says Kassa. “Are immigrants going to face deportation, often to countries they barely know, for relatively minor offenses, like jumping turnstiles on the train?”

“We fear that our families will experience violence and forced separation at a scale that’s unimaginable,” says Carl Lipscomb, a programs manager at the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, in an email.

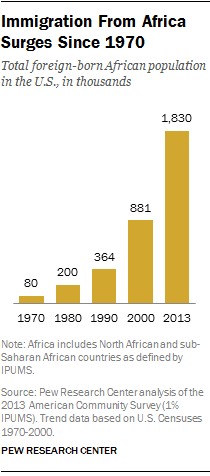

More African immigrants are calling the US home than ever before, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of census data. There were 1.8 million African immigrants in the country in 2013, double the population of 2000. The vast majority are lawful residents, who came as refugees from violent conflicts or with diversity visas for people from countries that are underrepresented in immigration to the US. But those who have temporary legal status are worried the government will deport them.

Many members of African Communities Together, for example, have Temporary Protected Status (TPS), a short-term clearance for people already in the US to continue to live and work here while their home countries recover from disasters. TPS has been granted to residents of six African countries (Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, South Sudan and Somalia) in recent years.

There are more than 300,000 TPS recipients, of which approximately 5,200 come from African countries, according to the Congressional Research Service (PDF). Kassa estimates about 200 of them are in his organization’s network.

More about the TPS program: Nepali immigrants who came to the US after the 2015 earthquake can stay a little longer

Some members have also received Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), an executive action by former president Barack Obama that gives temporary relief from deportation and work authorization to undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children.

Lawrence Bureh, 53, is a TPS recipient from Gangama, Sierra Leone. He’s very concerned. “My country should be considered for [a new] protected status,” he says. “There are still so many problems.

Both the health care infrastructure and the economy of Sierra Leone are still weak, in the wake of the Ebola outbreak that began in 2014. Bureh uses his salary as a security guard in New York to support his five children in Mauritania, where his family fled to escape the disease.

Jessica Vaughan, the Director of Policy Studies at the Center for Immigration Studies in DC, which supports tighter immigration controls, says expecting TPS for people from Ebola-affected countries to stop in May is par for the course.

“The temporary protected status was [a] response to the Ebola crisis,” she writes via email. “It is appropriate to allow it to expire.”

Last year, African Communities Together and the Black Immigration Network, successfully campaigned for one final extension of the TPS status, which will now end in May 2017 for Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. They fear, though, that the program will come under the scrutiny of the new administration.

More about African Communities Together: A hotline fights Ebola-related stigma against African immigrants

Bill Stock, president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, thinks that choosing not to issue a new TPS to the three countries will provide an early opportunity for the Trump administration to set the tone about limiting discretionary and humanitarian legal immigration programs.

Another signal is an executive order Trump is expected to sign that would both ban Syrian refugees and temporarily block others from several Muslim-majority countries, according to a draft obtained by the Los Angeles Times and other news outlets.

For DACA recipients, however, Stock hopes that the administration will seize an opportunity to champion a legislative fix that affects the 750,000 young people who have registered for the program.

“Taxpayers have already invested tens of billions of dollars in [their] education,” he says via email. “A path to legal status will result in a return on that investment.”

That none of this week’s executive actions directly address DACA recipients does not diffuse tensions at African Communities Together, though.

“Trump hasn’t moved to eliminate DACA immediately,” Kassa says, “but he also hasn’t taken any steps to protect or affirm it.”

The test will come, he says, when current beneficiaries will need to renew their applications to maintain the status. Until then, members who benefit from the program don’t know what their future will be. Which he says is a problem.

“A climate of fear erodes trust. It makes people feel that they don’t belong anywhere.”

The magnitude of the threat is pulling African emigres together, he says, even those from countries where protest politics are often met with violence or retribution. Kassa says the members of African Communities Together are convinced that these are not times “to keep their heads low.” He heard this comment at one of the group’s meetings: “We have a new president, but we don’t have a new constitution.”

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DWijb9OmtqNE

Kassa’s network has made common cause with other organizations to offer “Know Your Rights” legal clinics and assistance. They have also been using what they call “micro-radio,” mass call-in conference calls, with established networks of African churches, mosques, country associations and women’s groups, both in New York and DC, to disseminate updates and advice. They go into African markets, braiding salons and spice shops to talk to people one-on-one.

For now, attending Kassa’s meetings has helped Akinbode-Busayo put things into perspective.

“Before my mind was racing. What should I do? Should I leave the country’?” he asks.

“Trump says that he wants to get rid of immigrants who are criminals. So, I asked myself, ‘Am I a criminal? No.’ So, that gave me a kind of confidence.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!