Nuclear clean-up expert Lake Barrett at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in Japan, where the decontamination process will stretch on for decades.

Science journalist Miles O’Brien recently returned to Fukushima, Japan, for the sixth time since a massive earthquake and tsunami triggered a nuclear meltdown there nearly six years ago.

O’Brien thought he would be reporting on the massive clean-up effort at the shuttered nuclear power plant, a decommissioning effort that requires 4,000 workers to suit up in Tyvek suits, three layers of socks, gloves and respirators every day.

Instead, O’Brien found himself chasing a very different story about nuclear power.

“If the Japanese had either closed or improved those plants in significant ways, we would not have had the meltdown,” O’Brien says. “So the important question is: Is nuclear the villain here, or is it inattention to iterating and improving the technology?”

O’Brien reports in his NOVA documentary “The Nuclear Option,” which airs tonight on PBS stations, that 18,000 people died in the wake of the 2011 tsunami and quake in Japan, but no one has been killed by the radiation from the Fukushima meltdowns.

Meanwhile pollution released by burning coal and other fossil fuel power sources sickens millions each year.

As fears over global warming continue to simmer, nuclear power is experiencing something of a renaissance even as the Fukushima clean-up continues.

Solar and wind power hold promise, but storage problems mean neither can replace coal in the short term.

Solutions to those problems will emerge, O’Brien says, but “in the meantime we’ve got a problem that is immediate and we have some technology that could be available sooner.”

Reviving an old technology

Today, the nuclear fuel sources in most reactors are cooled by water. If the reactors lose power, as they did at Fukushima, those coolant pumps shut down, the water boils away and a nuclear meltdown ensues.

Reactors that can withstand a loss of power for longer are already being built in the search for better nuclear energy.

But a new, potentially safer, generation of reactors is also being developed by engineers and energy startups around the country.

According to O’Brien’s NOVA special, a DC-based think tank called Third Way found in 2015 that more than 40 startups across the US were developing advanced nuclear power designs.

These atomic business plans, they say, have garnered more than a billion dollars in investment.

Some designs rely on liquid metal sodium as a coolant instead of water. The liquid metal is better at absorbing heat, less risky when cut off from power and doesn’t require building massive pressure chambers around the nuclear fuel, O’Brien says.

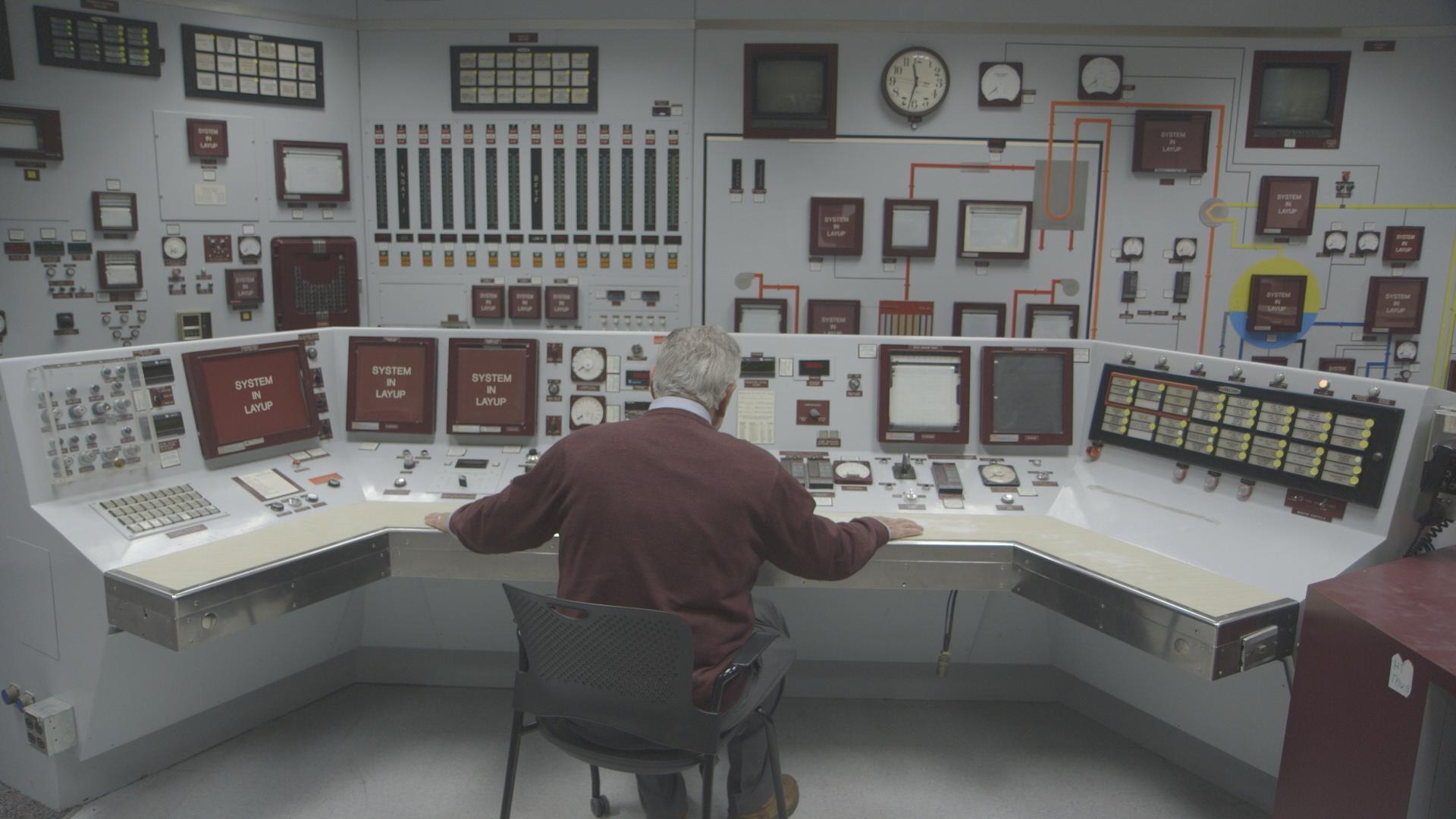

A liquid sodium reactor operated without incident for nearly 30 years at an Argonne National Laboratory testing site in Idaho. But nuclear power lost political support in the US after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, and the Argonne reactor was eventually moth-balled by President Bill Clinton.

“We got scared in the '70s and we walked away from this technology,” O’Brien says.

Now, the idea of cooling a reactor with liquid sodium is being revived by a generation of nuclear scientists and entrepreneurs who see climate change as a bigger threat than nuclear power.

The highest-profile liquid sodium project is being developed by TerraPower, backed by Bill Gates and his former Microsoft chief technology officer Nathan Myhrvold.

“From a technical perspective, we’ve solved every technical problem that’s occurred,” Myhrvold says. “But I can’t tell you, 'Oh yes, we’ve already been successful.' It’s going to be many more years of hard work before we are successful.”

“So we made a crazy bet," he says, "and we’re going to keep making that crazy bet."

Next-generation nuclear reactors have their risks too, of course. O’Brien says that liquid metal can be volatile when it comes in contact with water. And sodium-cooled reactors generate plutonium as a waste material.

“There are issues to work through here, but there’s no free lunch,” O’Brien says. “If you want the lights to go on 24/7/365, you kind of have to pick your poison. Maybe this is one way to do it, if we look at adopting the proper safety measures.”

The World has been reporting on stories about the human relationships at the heart of the atomic age. Read and listen to them here.