Can environmental protection and border security coexist? Not through an impenetrable wall, say Arizona advocates

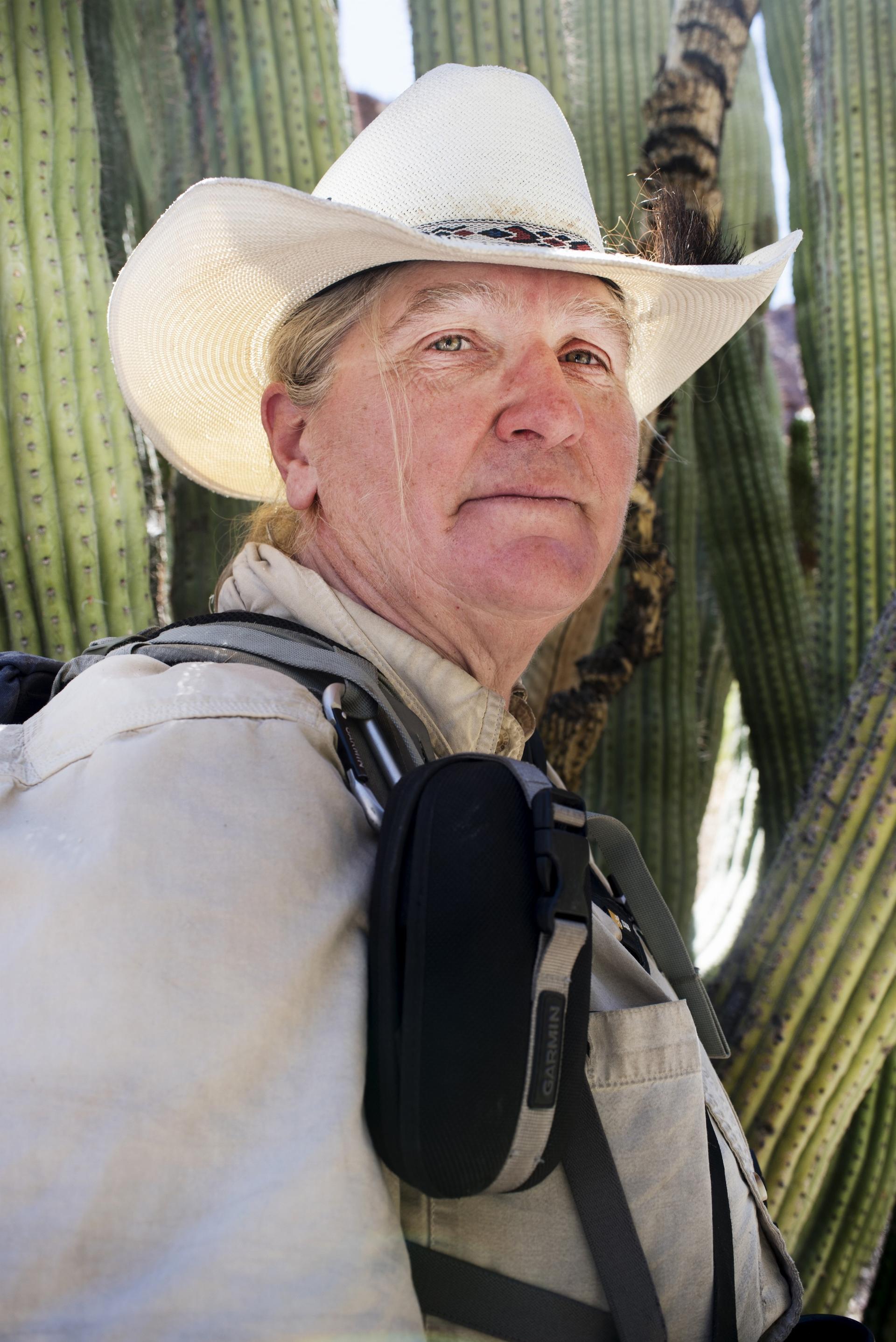

Driving up to a trailhead just a few miles from the US-Mexico border in Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, biologist Rosemary Schiano’s first advice is to cover our spare water gallons.

“People will break into your car if they see water, especially in this heat,” she says.

It’s just past 8 a.m. and the temperature in this part of the Sonoran Desert is already climbing above 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Arroyos slice into a mountainous expanse laden with Organ Pipe’s namesake cactus.

Schiano, an independent wildlife scientist, has spent nearly a decade combing through the border-hugging national monument and its surroundings, tracking humans’ impact on the area’s unique web of life.

But many others have also crossed this nature reserve. It’s been a dangerous place for migrants, drug runners and US Border Patrol (USBP) agents in their pursuit. And, if President Donald Trump has his way, a border wall will also cut through.

In August, the president alternated between threatening a government shutdown if Congress doesn’t include funding for the wall in the budget, and tweeting that Mexico will somehow cover the cost. Then last week, Republicans in Congress bristled when he said “the wall would come later” amid discussions with Democrats to pass legislation to protect some undocumented immigrants brought to the US as children.

Though its timeline and funding remain unclear, Trump’s wall has already pulled public lands into its crosshairs.

Border Patrol representatives in Texas confirmed last month that an initial portion of the wall slated for South Texas would cut through the Santa Ana Wildlife Refuge. In California, four companies were selected to build concrete prototypes of the wall — the state is suing, in part, they say, because the Trump administration failed to follow federal and state environmental protection laws. Homeland security waived 28 environmental protection laws in order to move forward with the bidding process there.

While discussions in Texas and California rage on, Arizona’s border and Organ Pipe seem to have been left out of the debate.

“This is designated wilderness managed by the National Park Service on a highly disputed border with so much anthropogenic activity impacting that wilderness,” she says. “There’s really no other place like it.”

Public lands like Organ Pipe account for more of Arizona’s US-Mexico border than in any other southern state, and most are already marked by some form of barrier. Another chunk of the international line sits on Tohono O’odham Nation land. Long before the Trump wall, Schiano says, this collision of security, conservation, humanitarian, and tribal interests set the stage for controversy.

“Everybody has a different mandate, so when you’re trying to enact them in such an incredibly fragile place, there’s a lot of conflict,” Schiano says.

Her work in the Sonoran Desert began with a trip to Organ Pipe in 2010. After years of being away from the area, she was shocked by the changes. Post-9/11 border crackdowns had transformed the once-remote outpost.

Security in border cities increased in the mid-1990s; policymakers argued that adding resources and agents would stall illegal traffic along the border. Instead, say advocates and onlookers, it funneled people into the remote wilderness. Border security efforts moved there too — USBP records show the Tucson sector’s staff rising from about 1,600 in 2001 to 4,200 in 2017.

“The vast majority of people used to come through the ports of entry in urban areas, but when this border security cat-and-mouse game moved into public lands, it really was a dramatic change,” says Randy Serraglio, the Southwest conservation advocate for Center for Biological Diversity. “All of a sudden you have thousands of Border Patrol vehicles and people moving around these areas where it had really never happened before.”

That struggle came to a head in 2002, when Organ Pipe park ranger Kris Eggle was killed in a gunfire exchange with drug smugglers from Mexico. Most of the park was then closed to the public for over a decade. The National Park Service (NPS) and USBP cooperated for its reopening in 2014, but years of shifting policy had taken its toll.

Border Patrol agents drove almost 17,000 miles through designated wilderness land in Organ Pipe in 2015 alone, according to data shared with PRI by a researcher formerly employed by NPS. Their tracks added to a collection of illegal roads etched by drug smugglers and immigrant activity in the early 2000s.

PRI made several phone and email requests to speak with representatives of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector, whose jurisdiction includes Organ Pipe, all of which were declined.

Rijk Morawe, the park’s current acting superintendent, would not confirm that mileage figure but remembers the 2014 co-agency cooperation as the start of a new era in the park that still prevails today.

“We’ve [USBP and NPS] come to a point where we’ve worked together, gotten the access we need and are being managed well,” he says. “We all need to respect each other’s missions; they get that, we get that, and it’s working.”

After the park’s reopening, the Department of Homeland Security funded a $3.9 million restoration project in southeastern Arizona, according to Morawe, part of which NPS used to repair some 50 acres of designated wilderness land damaged by Border Patrol vehicles in Organ Pipe.

The park official maintains NPS and USBP still coordinate well in Organ Pipe and believes the possibility of a Trump wall in Arizona is still too far off to comment on.

“Nothing has really changed for us, it’s pretty much business as usual,” he says. “Until we get direction that [a wall] is actually going to happen, there really isn’t any use pondering the what-ifs.”

Still, relations between NPS and USBP haven’t always been smooth in Arizona.

The Center for Biological Diversity’s Serraglio remembers an incident in 2008 when a new chunk of mesh border fencing near Arizona’s Lukeville crossing built up debris and caused heavy flooding on both sides of the border. Critics blamed the blunder on law enforcement’s failure to consult environmental groups and NPS stewards before construction.

Now, he worries the tenuous collaboration forged between NPS and USBP could deteriorate again.

“The Trump administration is definitely a threat to cooperation between agencies. There seems to be a real change in attitude by the Border Patrol recently,” he says.

In June 2017, Border Patrol agents arrested four undocumented immigrants in a raid on a medical camp run by aid group No More Deaths, located east of Organ Pipe, near Arivaca, Arizona. Activists say USBP violated an immunity agreement for humanitarian facilities that had been upheld by border security officials for years.

“We saw the [raid] as Border Patrol being given more leeway to be more aggressive in their enforcement policies, and to not respect the agreement we’ve had to be able to provide life-saving aid at our camps,” says Sarah Roberts, a registered nurse working with the group. “Maybe things will improve, but right now it looks like a permanent shift due to the political climate and administration.”

Felipe Jimenez, an Arizona Border Patrol agent and communications officer for the West-Arizona Corridor joint task force, says the Arivaca raid was simply agents following protocol.

“[Border Patrol] agents tracked illegal aliens into the camp and requested and were granted a search warrant based on probable cause,” he told PRI in an email. “[Pursuing those] harboring illegal aliens is not a policy change, it’s simply the law.”

Jimenez did not comment on whether a wall would benefit USBP operations in places like Organ Pipe, but did point to the agency’s Yuma sector. There, a 20-foot steel wall was erected around the San Luis Arizona Port of Entry in 2006, a move Jimenez says helped agents stall the flow of illegal drugs and human trafficking in the area.

“Infrastructure, technology and manpower have all played a significant role in the successes achieved along the international border in Arizona,” he said.

But Organ Pipe’s unique surroundings present entirely different challenges.

Just east of the park, the Tohono O’odham Nation’s ancestral land is split between northern Mexico and southern Arizona. Some 2,000 tribal members live across the border and travel to the tribe’s capital city of Sells for medical assistance and other services, and members from both sides carry out cross-border pilgrimages.

Special entry points along the border currently allow members to cross between the two countries. But Trump’s wall could cut right through the middle.

“We’re trying to make people aware that the O’odham are still here and still need to come back and forth,” says José García, the Tohono O’odham’s governor general in Mexico. “The wall would completely block that.”

The Center for Biological Diversity is also trying to tackle Trump’s plans on environmental grounds. A lawsuit filed in April with Arizona Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva calls for an expansive environmental impact study before plans for a wall move forward. This month, a similar suit filed by environmental groups took on the Department of Homeland Security’s wall plans in California.

During a drive deep into Organ Pipe, Schiano leads us to one of the park’s most striking barrier stretches: a section along its eastern-most boundary where a metal mesh fence breaks through the otherwise seamless desert sprawl.

Fifteen feet tall and stretching five miles along the international border, it’s part of the same fence that caused the massive flood in 2008.

Schiano scans the horizon where the towering fence ends and a squat wooden barrier begins.

“What I would like to say to the people who want to build an impenetrable wall is that there’s no such thing,” she says. “Walls ultimately don’t work, and they often end up causing harm to the very things we value most.”