Helping the blind ‘see’ the solar eclipse

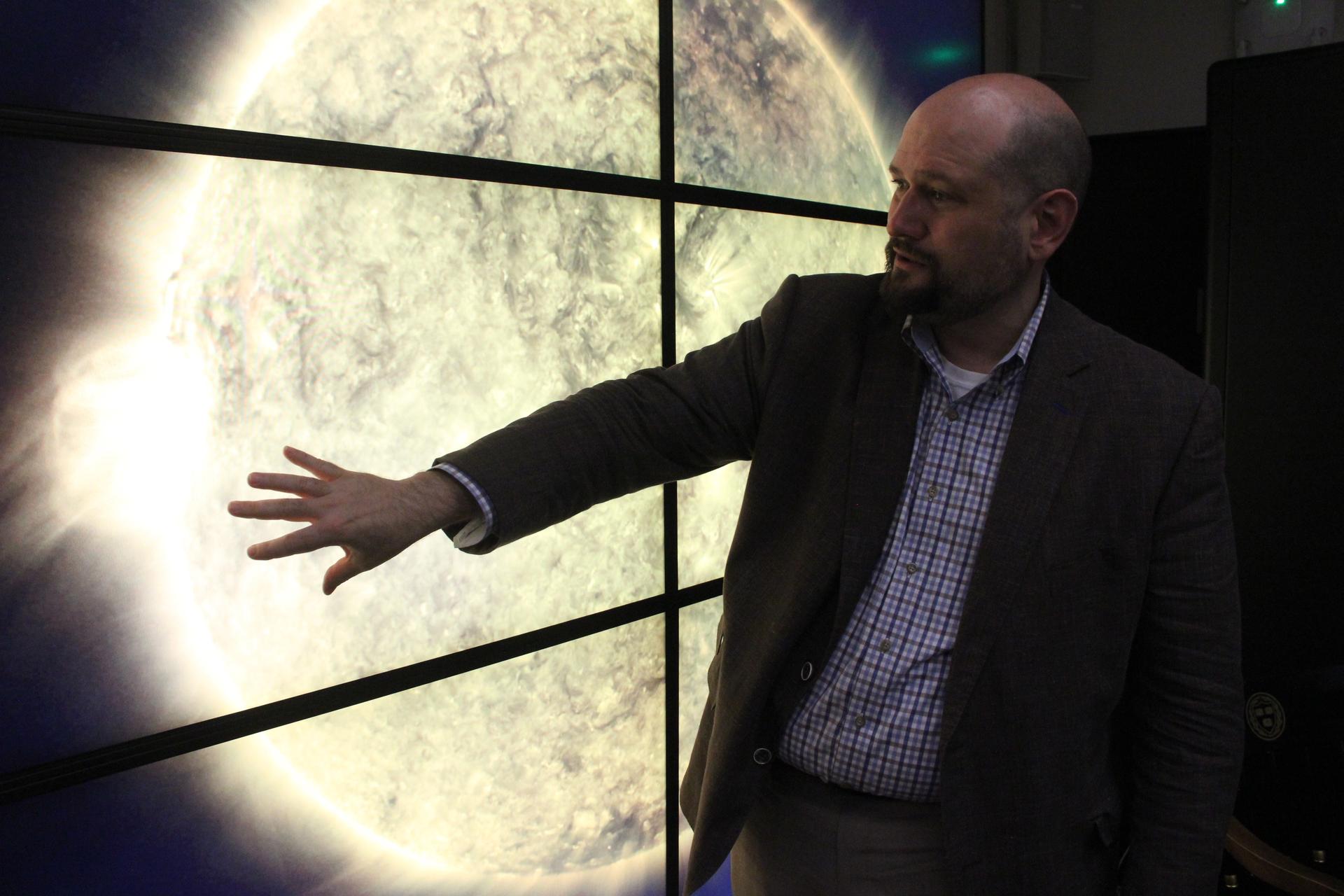

Solar astrophysicist Henry "Trae" Winter gestures toward a video wall depicting an image of the sun at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It sounds like the beginning of a riddle. How can someone who’s blind “see” the upcoming eclipse on Aug. 21?

It’s a question solar astrophysicist Henry “Trae” Winter started thinking about several months ago after a blind colleague asked him to describe what an eclipse was like.

“I was caught completely flat-footed,” Winter said. “I had no idea how to communicate what goes on during an eclipse to someone who has never seen before in their entire life.”

Winter remembered a story a friend told him about how crickets can start to chirp in the middle of the day as the moon covers the sun during an eclipse. So, he told his colleague that story.

“The reaction that she had was powerful, and I wanted to replicate that sense of awe and wonder to as many people as I could across the country,” Winter said.

So Winter, who works at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, decided to build an app to do just that: help blind people experience this summer’s eclipse.

“[The blind] community has been traditionally left out of astronomy and astrophysics,” Winter said, “and I think that that is a glaring omission that it’s time to answer.”

Eclipse Soundscapes, which launched for iPads and iPhones Thursday, features real-time narration of different aspects of the eclipse timed for the user’s location.

A “rumble map” allows users to hear and feel the phenomena when they touch photos of previous eclipses.

Dark areas in the photos, like the solid black face of the moon, are silent when you touch them. Wispy strands of sunlight radiating out from behind the moon emit lower hums. And touching brighter areas, like the shards of light that peek out from behind the moon’s valleys, produce higher frequencies.

The sounds are paired with vibrations, soft for darker areas and more intense for brighter spots.

“We managed to create frequencies that resonate with the body of the phone,” said the app’s audio engineer Miles Gordon, “so the phone is vibrating entirely using the speaker.”

A prototype for future tools

“The goal of this app is not to give someone who’s blind or visually impaired the exact same experience as a sighted person,” Winter said. “What I hope this is, is a prototype, a first step, something we can learn from to make the next set of tools.”

Other tools exist to allow blind people to experience the eclipse, including tactile maps and books, but it’s still understood largely as visual phenomena.

Less well-known are the changes in temperature, weather patterns and wildlife behaviors that accompany total eclipses.

Chancey Fleet, the colleague who first asked Winter to describe an eclipse at a conference months ago, was skeptical when she learned about his idea for an app.

“The first time I heard that blind people were being asked to pay attention to the eclipse, I kind of laughed to myself, and tried to contain my really dismissive reaction,” said Fleet, who’s an accessible technology educator at a library in New York. “It almost sounds like a joke.”

But after learning about the sounds associated with the eclipse, she’s interested in trying out Winter’s app.

“I’m looking forward to experiencing it for myself, and not just hearing or reading about it,” Fleet said. “Nothing is ever just visual, really. And [this] just proves that point again.”

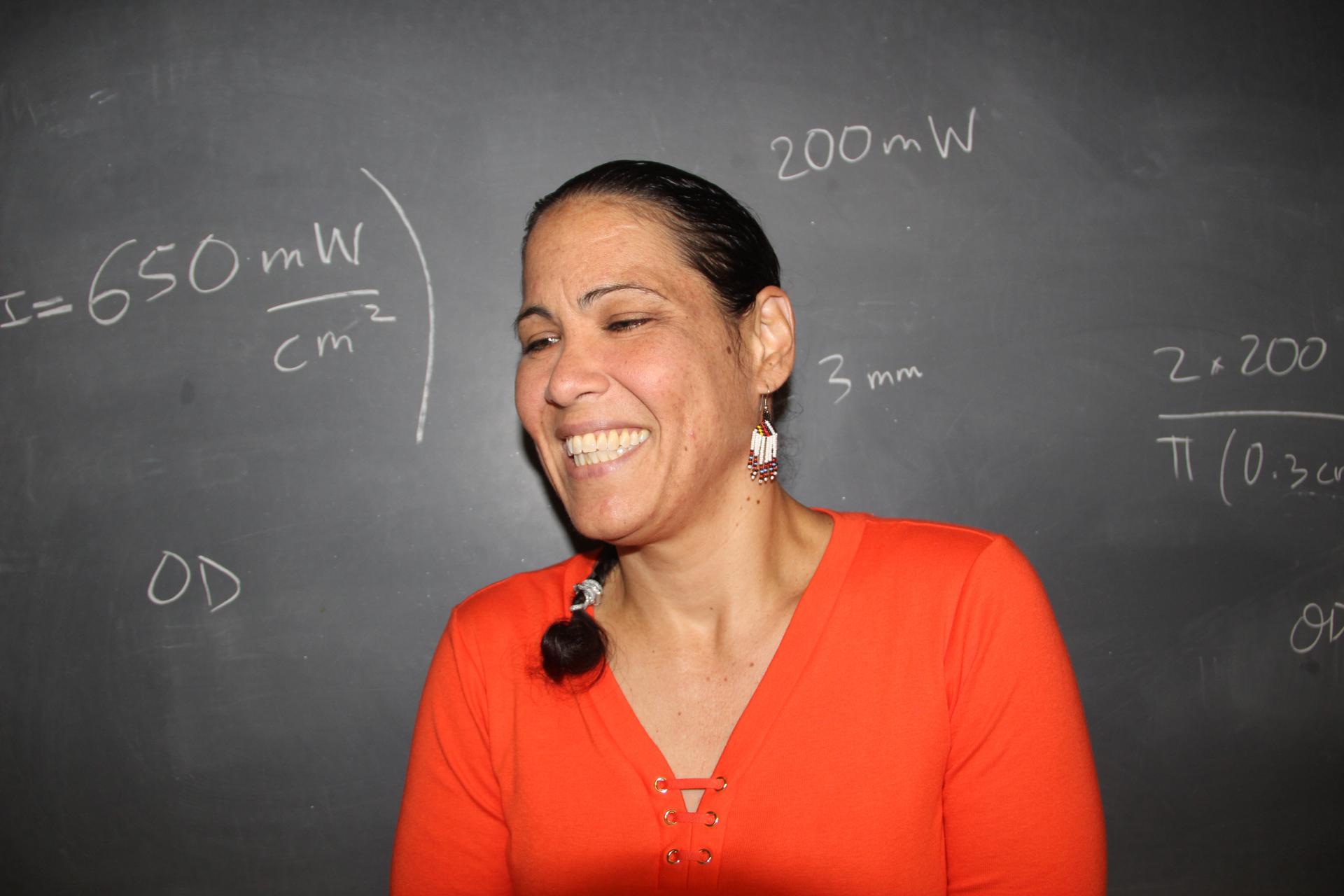

The app development team has gotten help from Wanda Diaz Merced, an astrophysicist who is blind, to make sure the software is easy to navigate.

She believes the app will show people that there’s more to an eclipse than spooky midday darkness.

“People will discover, 'Oh, I can also hear this!'” Diaz Merced said. "And, 'I can also touch it!'"

She also sees the app as a tool to get more blind kids interested in science.

“That is very, very, very important,” she said.

A longer-lasting legacy

The Eclipse Soundscapes team, which is backed by a grant from NASA, has recruited the National Park Service, Brigham Young University and citizen scientists to record audio of how both people and wildlife respond during the eclipse.

Phase two of the project is to build an accessible database for those recordings, so blind people can easily access them.

That’s the element of the project Diaz Merced is most excited about from a scientific standpoint.

After she lost her sight in her late 20s, she had to build her own computer program to convert telescope data to sound files so she could continue her research (here's her TED talk).

She hopes this project spurs more interest in making data accessible to researchers like her.

“What I do hope is that databases in science will use [this] database model … for us to be able to have meaningful access to the information,” Diaz Merced said. “And that perhaps through [the] database, we will not be segregated.”

In that way, she hopes the impact of the eclipse will last much longer than a day.

Tell us your eclipse stories here.